New Delhi: Balbir Singh, the sub-inspector in charge of the NRI murder case in the hit Netflix series Kohrra, is a brave hardworking cop by day and a drunk but loving grandfather by night. With his very human flaws, Singh is the antithesis of Amitabh Bachchan in Khakee and Ajay Devgn in Gangaajal — with their daredevil antics and trademark swagger.

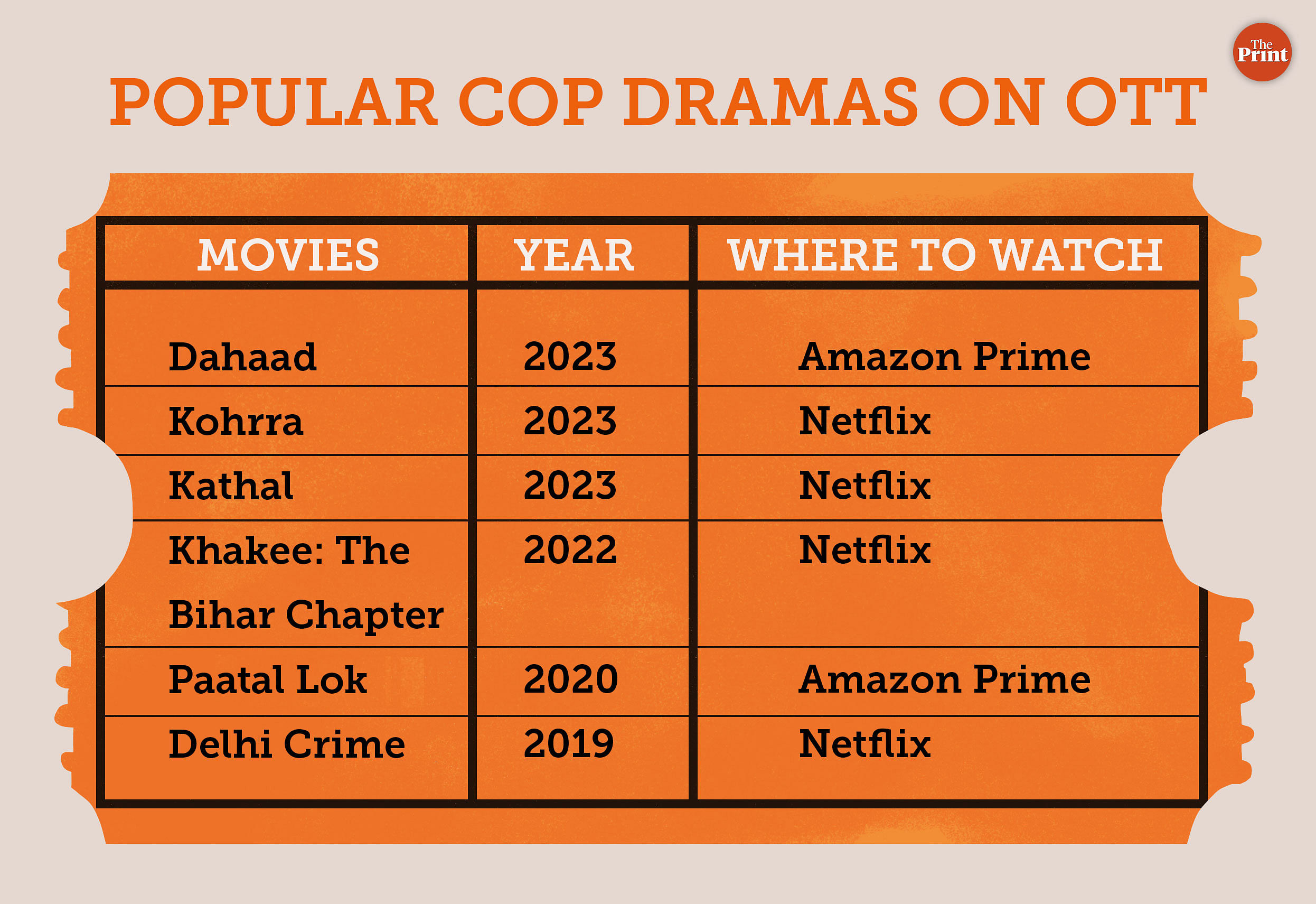

As cop dramas move away from Mumbai and Delhi into small towns and villages in Punjab, Rajasthan, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh, they’ve become grimmer, grittier, and grimier. This holds true for three of the most popular cop dramas and movies that were released on streaming platforms this year—Kohrra, Kathal, and Dahaad.

Whether they are looking for stolen jackfruits in India’s heartland (Kathal) or tracking serial killers in a Rajasthan village (Dahaad), the characters, their demeanour, locations, and even police stations are as real as it can get. Cops have always been integral to the entertainment industry, but where Bollywood bolstered the image of the macho, tough, and honest cop in a big city, OTT is revisiting chor-police drama through a more nuanced lens. The medium offers directors the luxury to weave in the personal with the professional.

Look beyond the trope

Kathal director Yashowardhan Mishra points to an audience that wants to see multidimensional characters.

“That is what stays with them. There’s also no pressure of numbers on OTT, and that is crucial for any art to thrive,” he says, having come up with the idea 10 years ago.

“I felt it was necessary to research and talk to real cops of the region to understand the realities of their lives and intersectionalities that exist in society.”

Amazon Prime Video’s police procedural Paatal Lok (2020) heralded this granular, visceral, close-to-reality trend. As Namrata Joshi wrote in her review for The Hindu, “…it’s not the glamorous, adrenaline-pumping action and the spectacular car collisions straight out of a Rohit Shetty universe”. She goes on to write that the cops here are cynical, the police stations are grubby, and the hotels seedy.

“We have always had very heroic representations of [a] cop, who will either do anything for his job, or a corrupt policeman. I wanted to change that with Paatal Lok,” says co-writer and creator Sudip Sharma. So, inspector Hathiram Chaudhury (Jaideep Ahlawat) juggles his son’s adolescent angst and household drama with the brutality and politicking of his work. And the setting is not South Delhi — but Jamunapar or East Delhi.

The writers visited police stations and looked at every minute detail — from where the files were kept, the state of lock-up, to cops’ daily demeanour. This was the scaffolding on which Paatal Lok was built.

Almost a decade before Paatal Lok, director Anurag Kashyap explored this underbelly of procedural crime drama through the duology Gangs of Wasseypur and later with shows like Mirzapur (2018), Asur (2020), Jamtara (2020). He shifted the gaze to small-town crimes and their crime lords. And in the subsequent years, the camera zoomed in on the cops who bring down the criminals.

So, Balbir Singh (Suvinder Vicky) and his partner Garundi (Barun Sobti) drink together and bond over their dreams and frustrations. Singh struggles to support his daughter, who is desperately trying to escape an unhappy marriage. It triggers flashbacks of his own troubled marriage. These scenes humanise the sub-inspector from a small town in Punjab.

Now, the police are more than the cases they solve.

Also read: Hijab, halal, football, food—Kerala has a new film industry. It’s Malabar Pride

Breaking stereotypes

The explosion in the number of OTT platforms and the 24×7 churn of content machines has created a huge demand for screenwriters, scriptwriters and storytellers in India. Now, they are coming from all over the country, not just Mumbai, Delhi, or other big cities, and leaving their imprint on the movies and series they write.

Dahaad co-director and screenwriter Reema Kagti was born and raised in Borhapjan in Tinsukia district of Assam, while Sudip Sharma is from Guwahati.

“The North Indian small town has always held a fascination for me, and I have looked at it through the lens of an outsider, even in Paatal Lok,” says Sharma.

It helps if the team comes from varied backgrounds. “You cannot write in absentia. I have a team of writers who come from different places, and they all added their own experiences in the writing of Dahaad,” she says.

For decades, authors, journalists, and film directors have plumbed the depths of Mumbai’s mafia, from Haji Mastan to Dawood Ibrahim and Chhota Rajan to Arun Gawli. But there are only so many ways to tell the same story—clichés and all. Delhi has a history of high-profile cases, from the 1995 Tandoor murder to the 2006 Jessica Lal case. But small-town India is primed to get its crime on OTT. And writers want to smash prejudices.

“I definitely had a stereotype of Bihar because of the representation,” says actor Karan Tacker who plays IPS officer Amit Lodha in the Netflix web series Khakee: The Bihar Chapter. Being a part of the series was an eye-opener for him.

“We shot in Jharkhand, and it was beautiful and lush, unlike the dusty, dry picture I had in mind,” he says. The unit travelled to other parts of India’s heartland like McCluskieganj, Daltonganj, and Hazaribagh. Often, there were no hotels, so they stayed with local residents in their homes.

The one stereotype that Tacker wanted to break while playing IPS Lodha was that of the heroic cop.

I did not want to play the character heroically because I feel like the hero is the job and the uniform. I wanted the humanity of the person to come out, he says.

In Khakee, the title track Humra Bihar Mein establishes what the show is about. “There’s a lot of peeping into the world of Bihar. You get glimpses of what happens in trains, police stations, and a village. The show probably takes you to the heartland, and you get to meet the people there,” Neeraj Pandey told Film Companion.

Meanwhile, Kathal looks inward. It satirises the police system, looking at how local MLAs in a small village in Bundelkhand dictate which cases get priority, even if it’s the theft of jackfruits over missing girls.

“I felt like with mature language and certain scenes, the family audience had no access to cop dramas. I wanted to change that with Kathal,” says Mishra. The process of research was also a process of unlearning for the writer-director.

Mishra spent years researching and finalising the plot, which is inspired by a real-life story of two jackfruits being stolen in Delhi from an MLA’s house and a police station going into a tizzy trying to locate them. Mishra finally decided to change the lead protagonist from a male to a female cop to bring in more intersectionality.

He also realised that face-offs with criminals are not always the main concern for police personnel.

“One female cop told me that when they go to villages, they are more concerned about the unavailability of proper washrooms. That challenged my own ideas about cops and their work” he says. “I spoke to many female cops, and the characters of the cop Kunti, who refuses promotions because her husband has a stable job and cannot transfer, the lead Mahima, are all inspired by real female cops.”

Kohrra smashed Bollywood’s extravagant, opulent portrayal of Punjabi culture through its layered characters. No one is truly likeable in this series.

“It is, after all, human nature to stand in the dung and conveniently ignore it. That was something Kohrra challenged in terms of Punjabi stereotypes,” says Sobti.

Real locations, real dialogues

The authenticity goes beyond cosmetic changes. Interrogation rooms are no longer boxy rooms with the standard low-hanging bulb over a table that the policeman bangs every time the detainee is asked a question. This new crop of police procedurals does not sensationalise police brutality, but neither does it shy away from the subject. It’s a matter-of-factly treatment of police violence, and even caste discrimination for that matter, which jolts the viewer out of any complacency. In Kohrra, for instance, a female constable leads an interrogation by tying up Veera (Aanand Priya) whose fiance is found dead, and proceeds to beat her brutally in a stuffy room.

“While doing recce for Paatal Lok, we came across a police station in Delhi’s Shalimar Bagh that became the inspiration for how the station would look in the series. For Kohrra, it was modelled like a small-town police station, which usually has a courtyard. We turned a school into one,” says Sharma.

The police station in Khakee’s Sheikhpura village is more like a small hut. But it does not pander to the exoticised gaze that Bihar has been subjected to in Hindi films.

“I think in the middle-class mind, there is the idea that we need to avoid police stations, and we also have a very standard understanding of what they look like. And we did not want it to happen in Paatal Lok or Kohrra,” said Sharma.

The writers, too, wanted to create characters who happen to wear uniforms, and not the other way round. And they achieve this — or try to — through dialogues that are neither grand nor oratory. Instead, they border on crass at times.

In Kohrra, Garundi, a rookie cop, asks Balbir where Machu Picchu is, to which the latter replies, “It is in the ass.” It sets the tone of the relationship between the two—it is a mentor-mentee bond, but one that avoids overt displays of concern.

Ahead of shooting the series, the cast attended an acting workshop to really get under the skin of the characters they were playing.

“For me, it was relatively easy because I have played a cop before for the Punjabi language show CAT. I know people in my family who are in the police force. But I strongly feel Balbir could have been any man in any profession,” says Suvinder Vickey who gave a breakout performance in the web series.

This is also consistent with sub-inspector Anjali Bhaati (Sonakshi Sinha) in Dahaad. She shoots and kills but exhibits no unnecessary macho traits to show a position of power.

Shefali Shah’s Vartika Chaturvedi in Delhi Crime Seasons 1 and 2, one of the best portrayals of senior police personnel in recent times, belongs to an ‘upper’ caste but does not play to the assumptions of a ‘boss lady’ stereotype. Though she is addressed by her team as ‘Madam Sir’, Vartika does not display any macho behaviour. Rather, she is calm, collected, and even vulnerable, but never without a grip on what is happening under her leadership.

Dahaad is loosely based on the serial killer Cyanide Mohan and examines caste through its inclusion of a powerful Dalit protagonist, Bhaati. She faces caste-based discrimination every day on the job. Junior officers light incense sticks to ‘ward off’ her influence; men harass her every now and then. When she is denied entry inside a house, Bhaati says: “Kaun unch kaun neech, ye tere pushton ka time nahi hai, Sanvidhaan ka time hai, kayde kanoon ka time hai (Who is forward, who is backward; this isn’t the time of your forefathers; it is the time of the Constitution, it is the time of the law)”.

For the most part, the quintessential police officer in Indian cinema is inevitably upper caste. Even our favourite onscreen women police officers—Sushmita Sen as Malvika Chauhan in Samay (2003) or Rani Mukherjee as Shivani Shivaji Roy in the two instalments of Mardaani, and Shefali Shah’s Vartika Chaturvedi in Delhi Crime.

Also read: Kerala’s indie films are stuck in bureaucratic belly. No theatre fans or OTT buyers

Starting a dialogue

The year 2023 is proving to be different. Bhaati in Dahaad and Mahima Basor in Kathal are Dalits. “Initially, I had a macho image in mind to play a police inspector. After meeting female cops, I realised that my character can be feminine, too. Mahima wears a nose pin, earrings and even make-up,” Malhotra told The Indian Express in an interview. This point is also corroborated by Mishra, who spoke to a female cop who detested the idea of having to resort to violence.

“When you have power, you do not scream from the rooftops. In fact, to get a point across, the calmer you do it, the stronger you will be able to get it across,” said Shefali Shah in a 2022 interview with ThePrint.

Cop dramas have opened up the space for storytelling that does not focus solely on the criminal and the cop, the good and the bad. It has also created the space for a masala venture like the Singham franchise to co-exist with the gritty, murky tellings of Kohrra or Paatal Lok.

What also buttresses these nuanced and varied portrayals is doing away with the 2.5 hour-film format. “To be honest, since we were making Kohrra for OTT, we didn’t have the pressure of the box office collections. It was much easier for us to tell the story we wanted to,” says Gunjit Chopra, one of the writers of the series.

And the audience is responding to the new kinds of cops on screen by generating conversations around class, caste, and gender. “A lady texted me that her 11-year-old daughter watched Kathal multiple times and has been asking questions about caste. She wanted to thank me for helping to initiate this kind of conversation at home,” says Mishra.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)