Kozhikode: Kerala’s Malabar region has a PR problem — from Malappuram being called mini-Pakistan by Home Minister Amit Shah to Kannur being labelled one of India’s most politically violent districts. But in the last 10 years, Malabar has found new spokespersons. Directors, scriptwriters and producers are giving the region a makeover.

One of the biggest Malayalam hits of 2022, Thallumaala, is set in Malappuram. In the first fight of the film Wazim, played by Tovino Thomas is thrown into the mosque’s ablution tank, as the imam’s sermon plays in the background. The setting is undeniably Muslim, but the conflict is universal—Wasim placed his muddy shoes on the pristine white sneakers that belong to Jamshi, played by Lukman Avaran.

This blend of hyperlocal and universal has come to define Malayalam cinema’s new wave. Now there’s a new player on the block—Malabar New Wave. The food, the language and the sartorial choices of Kerala’s Muslim-majority districts are now centre stage.

“There are two things that define the Malabar region—the love for football and food,” says Zakariya. His debut film Sudani From Nigeria revolves around sevens football.

The Malabar region of Kerala—Palakkad, Malappuram, Kozhikode, Kannur, Kasargod, and Wayanad—has the highest concentration of Muslims in the state. From Hijab to halal, bias to biryani, Islamophobia to identity, Malabar New Wave is a powerful antidote to The Kerala Story phenomenon. While the number of big releases can be counted on one’s fingers their impact has not just created a subculture but also disrupted the industry.

The cultural and working landscape of the Malayalam film industry has historically been dominated by the twin bastions of Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram.

Thiruvananthapuram, a film industry bastion of the 80s, is often associated with political and satirical plots. Prominent figures of this style of cinema include Mohanlal and Priyadarshan. Kochi’s identity is intertwined with crime and the underworld and more recently has been the preferred backdrop of Left-Liberal filmmakers such as Aashiq Abu, and Rajeev Ravi.

Now, you do not have to be from Kochi or Thiruvananthapuram or even live there to be a filmmaker

-A director who requested anonymity

Zakariya’s film is often credited with catapulting Kerala’s Malabar region to prominence not just in Mollywood but beyond, into the gaze of Indian and world cinema. People were curious about the kind of stories coming out of the region.

Director-screenwriters Ashraf Hamza, Muhsin Parari and Zakariya became synonymous with this new wave of storytelling. This rise of talented writers, actors, music producers and directors from the Malabar region also signalled the de-centralisation of the Malayalam film industry.

“I have grown up watching film shoots close to my house in Kochi. But now, you do not have to be from Kochi or Thiruvananthapuram or even live there to be a filmmaker. The story and vision is all that matters,” says a director who did not want to be named.

Also read: Kerala’s indie films are stuck in bureaucratic belly. No theatre fans or OTT buyers

Flavour of the North

Calling this off-shoot of new wave cinema a Muslim phenomenon is a misnomer. But it is definitely a sort of Malabar Pride that is taking shape in popular culture.

Thalassery city is a character in Thattathin Marayathu (2012) that follows a Hindu-Muslim college romance, Malappuram is the stage for Sudani From Nigeria (2018) and its bromance between a local football coach and a Nigerian player, Kasargod’s courts play a pivotal role in a former thief fight for justice in Nna Thaan Case Kodu (2022).

The directors, writers, and actors are not necessarily Muslim nor are they telling Muslim stories. Their stories are situated in their realities.

“The stories I have written or directed are about the Malabar region. Even my upcoming films are. So I asked Muhsin [Parari] if we are consciously doing this,” says Zakariya. “Muhsin told me to stay true to the stories. That is what I am doing,” he adds.

The story revolves around a Nigerian refugee, Samuel (Samuel Abiola Robinson) who’s part of a sevens team managed by Majeed (Soubin Shahir).

Zakariya and Parari, who wrote the script, make sure their characters’ Muslim identities are known—there are visits to the mosque, and prayer rituals. But what sets Malabar New Wave apart is that the stories don’t revolve around the characters’ religious identities.

“They paint an endearing portrait of a Muslim community – sorely needed as Islamophobia engulfs India – without overtly stressing their religious identity,” writes critic Anna MM Vetticad.

Thallumala, the biggest hit of the genre, was also co-written by Parari, along with Ashraf Hamza. The two protagonists are Muslim—a Dubai-bound Wazim, played by Tovino Thomas, and a Dubai-return Fathima Beevi, played by Kalyani Priyadarshan. A reflection of North Kerala’s connection to the Gulf. But the host of supporting characters includes Hindus and Christians.

“…worth noting is the normalised representation of Muslims in Thallumaala, and Christian characters shown as being not particularly different from them,” writes Vetticad.

While it was critically panned, the film quickly achieved cult status for its depiction of the aspirational generation of Malappuram youth — flashy (and often fake) designer clothes, influencer culture, the proclivity to solve any and all conflict with violence, and mala paatu (Muslim ballads).

“We do not have a culture of pubs or concerts. Movies are the only form of entertainment for young people. But we did not anticipate the kind of response we get,” says director Khalid Rahman.

The use of Malappuram slang and dialect also contributed to the film’s popularity. “The rebellion of turning my native dialect, culture and beliefs, which at one time used to be considered ‘uncivilised’ and made me feel less-than, into the stylish aesthetics of a movie was the challenge I wanted to take on,” says Parari.

We do not have a culture of pubs or concerts. Movies are the only form of entertainment for young people.

– Khalid Rahman, director

The film KL 10 Patthu (2015), directed by Parari, is a reference to Malappuram’s vehicle registration number. It is references and callbacks like these that shape the Malabar films. It is an exploration of northern Kerala beyond what is presented by those not from the area, it’s a shifting of perspectives.

Zakariya’s film Halal Love Story is the epitome of this shift. It follows the challenges of making a ‘halal’ telefilm.

He wrote the script with Parari, his friend and constant collaborator. The comedy-drama zooms in on the concept of halal, not with criticism but with acknowledgement of social-religious practices in place within the region’s Muslim community. It neither condemns, nor justifies, and instead balances the gaze in a manner that shows what life looks like for most Muslim families in Malappuram.

With the evolution of the genre and the establishment of a commercial audience stories from the region are becoming more diverse. Nna Thaan Case Kodu, which swept the 53rd Kerala State Film Awards with seven awards, is a political satire set in Kasargod.

There is only one Muslim character in the movie but the film is distinctly Kasargod—from the dialect to the cultural references.

For director Ratheesh Balakrishnan Poduval, grounding the film in Kasargod was about finding less explored destinations in Kerala.

“Kumbalangi Nights (2019) brought the first shift because no one thought a film could be made on the region. And now, there are people looking for newer places,” says Shamal Sulaiman, director of Jackson Bazaar Youth (2023).

Also read: ‘You don’t look Malayali enough’. Once rejected, Tovino Thomas is Kerala cinema’s rising star

Many Muslims, not enough stories

It is not that Kerala’s film industry does not have big Muslim names. Mammootty, one of the industry’s biggest stars is Muslim, his son Dulquer Salmaan is also a star in his own right. Fahadh Faasil, one of the industry’s most bankable stars, is also Muslim. Directors to producers to music directors, there are many Muslims, but not enough Muslim stories.

It is no different than Bollywood, where the Khans may rule the box office, but they primarily play Hindu or Punjabi North Indian characters.

And even when Muslim characters find space in films, the Muslim experience does not. Either their religion is incidental or made into a caricature.

“Muslim representation in terms of characters almost completely died out with the coming in of television,” says senior critic CS Venkiteswaran. He adds that films were being shot in Kozhikode in the 1980s and 90s that had Muslim characters but that ended when family audiences moved on to serials.

“The serials would be primarily Hindu, and look at relationships, family and love. For a whole decade, TV had a massive impact on what was being made in cinema,” he says.

Vineeth Sreenivasan’s Thattathin Marayathu (2012) is the movie that brought north Kerala back into the popular imagination. It wasn’t the first to be shot in the Malabar region, but among the new wave films it is arguably the one that used the region as more than just a backdrop.

Thalaserry, a municipality in the Kannur district, is as much a character as the actors. The movie also brought the hijab into mainstream conversations—it became desirable. The Nair protagonist, played by Nivin Pauly, is fixated on Aisha’s (Isha Talwar) head scarf, to him it is when she wears the hijab that she’s at her most beautiful.

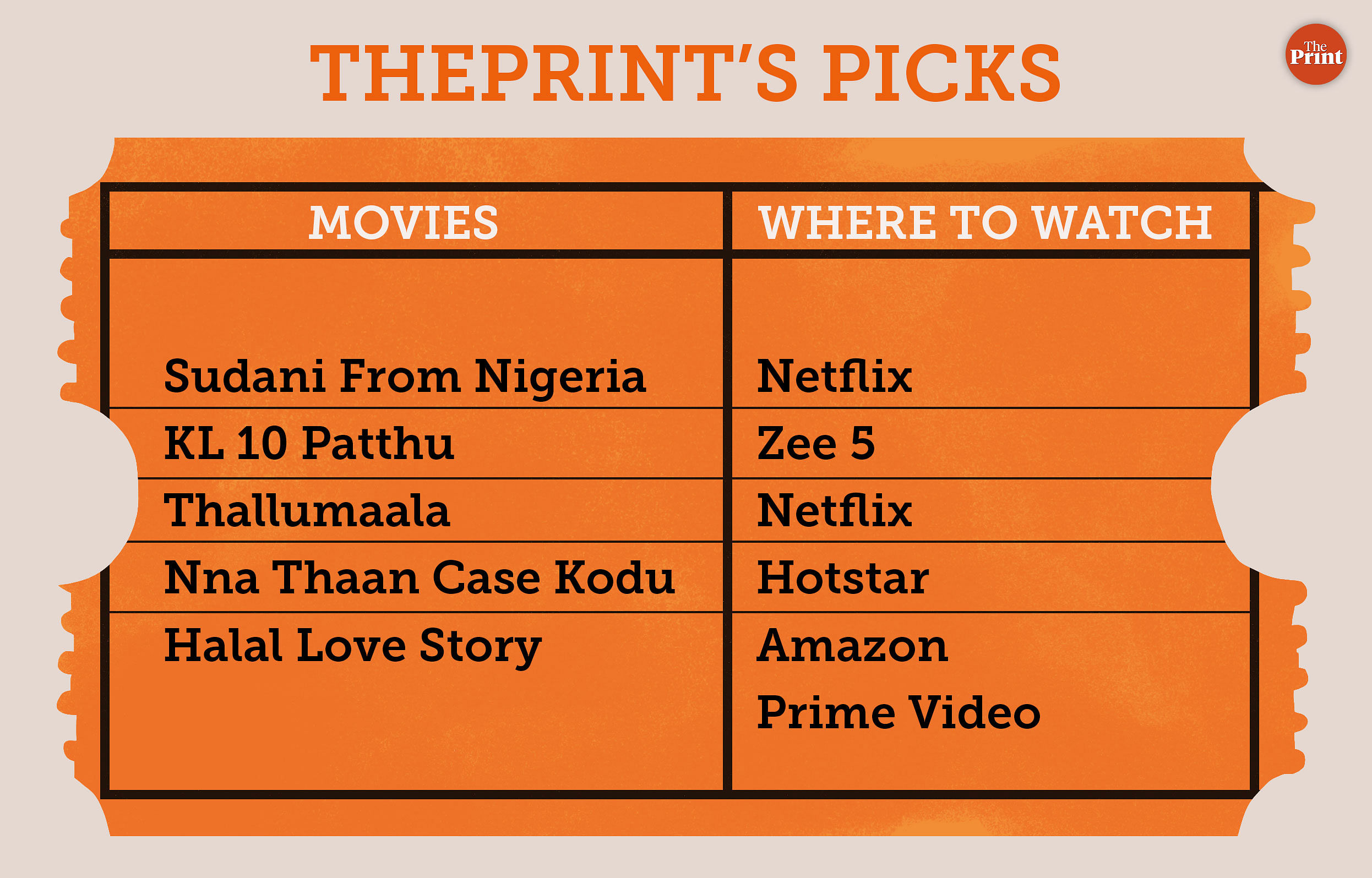

The genre slowly took root with movies like KL 10 Patthu (2015), Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum (2017), Sudani From Nigeria (2018), Tamasha (2019), Halal Love Story (2020), Thallumala (2022) and Kadina Kadoramee Andakadaham (2023).

It is important to distinguish between films that were shot in the Malabar region and Malabar New Wave. Virus (2019), Bheemante Vazhi (2021) are two films that were shot in north Kerala but don’t carry the flavour of the region.

Also read: Basil Joseph perfected small-town Kerala stories with global appeal. Next, pan-India success

Beyond stereotypes

A key feature of Malabar New Wave is communal harmony. But it’s not heavy-handed. In Sudani from Nigeria, the Muslims in the village pray for the better health of the Christian Nigerian Samuel. In Thattathin Marayathu, a Hindu man opens a shop selling hijabs.

“We have grown up in communal harmony, taking part in both temple and mosque activities. Now, it is seen with awe. But it has always been so in my hometown,” said Zakariya, who’s from Malappuram.

While the films are not exclusively Muslim, their portrayal of Muslim characters is a key feature.

Thallumaala’s Wazim and Beepathu, Thattathin Maraythu’s Aisha, Sudani from Nigeria’s Majeed are all unmistakably Muslim. But their religious identity doesn’t define them.

We have grown up in communal harmony, taking part in both temple and mosque activities. Now, it is seen with awe. But it has always been so in my hometown

-Zakariya, director

In fact, the USP of Thallumala’s writing is the lack of suffering and misfortune, often synonymous with Muslim representation in Indian film.

“In the wedding scene Beepathu wears an Arabic-inspired outfit because people in the Malabar region are very inspired by both customs and food of the Gulf, and we wanted to show that,” says Rahman

For Rahman however, it is not necessarily a ‘Malabar’ aesthetic.

“I am from Kochi, and in that way, I would not even be a part of the cadre of Malabar filmmakers,” he says.

But being from the region is not a prerequisite for making Malabar New Wave. Kochiite filmmakers Shyju Khalid and Sameer Thahir were part of the crew of Sudani From Nigeria.

From homes to the silver screen

Malabar New Wave did not grow from vacuum, it evolved from Malabar ‘home films’.

Salam Kodiyathur, a school teacher in Malappuram, was part of an active professional troupe of actors performing theatre. They told their own stories. Then came cable TV in the 90s. It was a death blow. People were now glued to their television sets.

The serials would be primarily Hindu, and look at relationships, family and love. For a whole decade, TV had a massive impact on what was being made in cinema

– CS Venkiteswaran, film critic

Kodiyathur decided to make his own films, and thus ‘home films’ were born. The idea was to make Muslim socials, with a bare minimum budget, and distribute it through CDs. It was sold at Rs 250 per movie, and per day rent would be decided by the CD shop owners.

The business made perfect sense in the Malabar region, where many Muslim families, especially women, would not consider going to the theatre.

In 2000, Kodiyathur converted a play Ningalenne Branthanakki, into the first home cinema. He financed the film himself and lost almost all of the money. His first three films made no money. But that did not deter him.

“I gave an opportunity to new actors, who were ready to act if I provided their food and travelling fee. We mostly shot in villages and small towns, and that also helped cut costs,” says Kodiyathur.

By 2004, Kodiyathur had shot his first film abroad, in Qatar, Parethan Thirichu Varunnu.

His films gave a voice to the lives and experiences of the Muslims in the Malabar region, especially of the middle and lower classes. The actors too, would belong to these sections of the society.

The films depicted the struggle of migrant workers in Gulf countries and the family lives of Muslims, especially in rural spaces.

“People would return from the Gulf, buy the CDs from here and take them back. They were also copied and sold in black,” says Kodiyathur. Slowly, this small cottage industry started receiving financial backing from businessmen.

With the coming of the internet and smartphones, home cinemas no longer held the same appeal. Kodiyathur still makes movies—he uploads them on his YouTube channel and gets revenue from advertisements. But it is not very lucrative.

Kodiyathur is however proud of the contribution he has made to the cultural landscape of the Malabar region, and also the voice he gave to those who never had it. “Even Mammootty played a character [in Bavuttiyude Namathil (2012)] who wants to act in a home movie,” he says, beaming.

Reverse propaganda?

The Kerala Story, is an antithesis of everything the Malabar New Wave hopes to do. The Sudipto Sen film depicts Kerala Muslims and the Malabar region in a manner that is severely damaging and blinkered. The film raked in Rs 240 crore.

The Malayalam film industry too is not without its own biases. Even as more Muslim narratives are finding a foothold, Islamophobia looms. “I was narrating a story to a producer, and he said that I do not want Muslim stories,” said a young director, who did not wish to be named.

For critics like Venkiteswaran, the conspicuous absence of problems within the community is a matter of concern. “It looks like everything is happy and problem-free for Muslims in Malabar, or there are no prejudices, biases or harmful practices,” he said.

These problem-free positive depictions have also given rise to accusations by movie-goers that the Malabar gang— Zakariya, Parari, Hamza, etc—are funded by Muslim religious outfits. The most common charge on subreddits dedicated to Malayalam movies is that they are “propagating Jamaat-e-Islami Hind values”.

“Of course, I have heard these statements about me. But, I want to ask what propaganda am I pushing,” says Zakariya.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)