All the critics raved about Shruthi Sharanyam’s debut Malayalam indie film B 32 Muthal 44 Vare on breast and body shaming. OTT platforms like Manorama Max and Sony Liv wanted to buy it. The movie ran for a week in theatres in January —and then it vanished. Now, B 32 Muthal 44 Vare languishes in the bureaucratic belly of the Kerala State Film Development Corporation, which produced the movie. It will not let Sharanyam sell it, either. The Kerala government wants to run the movie on its own OTT platform. Except that this streaming initiative has been in the making since 2016.

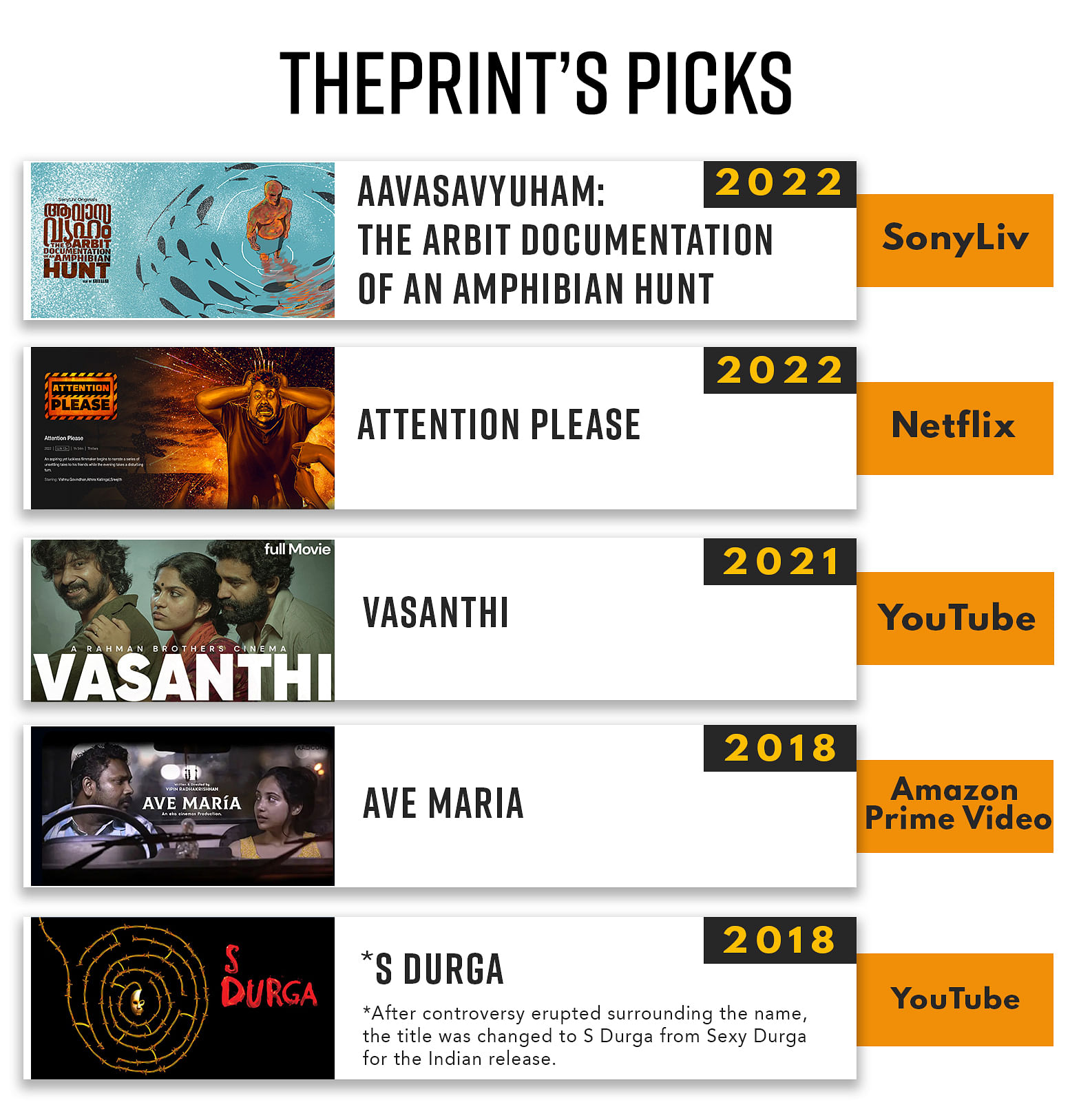

With movies like Aavasavyuham: The Arbit Documentation of an Amphibian Hunt (2022), 1744 White Alto (2022) to Nila (2023), Kerala’s independent film scene appears to be thriving, at least when compared with the likes of Bollywood or Sandalwood.

The movies run to full houses at the International Film Festival of Kerala. But once the curtains close and the spotlight fades, many young directors find themselves at square one.

Within the Kerala indie film community, disillusionment is setting in.

Even in Bengal, another regional cinema powerhouse that also has space for independent filmmakers, the story is not very different. In Kerala, it’s more surprising because of the huge govt support it has through the KSFDC and Chalachitra Academy, which other states don’t have. The physical manifestation of this is IFFK, which is always a hit and all these indie films run to packed theatres and get rave reviews. So it’s surprising when it doesn’t work theatrically. There’s also a stereotype that Kerala has high film literacy and appreciation because a lot of the film culture is rooted in the state’s literature. So again, it’s a shock when this doesn’t translate economically. A Bengali director shared that IFFI-K audience was always a mix, and it was a sign of encouragement, as at least for the festival days, indie films would be watched with as much enthusiasm as commercial ones. This is absent in other industries.

There is no consensus on how to strictly categorise Malayalam indie films. Jeo Baby’s breakout film, The Great Indian Kitchen (2021), was made on a budget of Rs 2 crore over 27 days. But for most struggling filmmakers, Rs 2 crore or even a crore is a luxury, especially when such films are being shot under Rs 1 lakh budget. Krishand, however, defines indie films as those made under Rs 2 crore. With no funds to rope in big stars, indie filmmakers rely on strong scripts, innovative shooting and budgeting tricks.

“The cost of Mohanlal’s caravan can fund at least four independent films. So why would [such] filmmakers get a big star?” said one director who did not wish to be named.

Also read: ‘You don’t look Malayali enough’. Once rejected, Tovino Thomas is Kerala cinema’s rising star

The sorry hype

Indie movies, once an integral part of Kerala filmmaking, are being pushed further to the fringe, say directors, scriptwriters and producers.

“The kind of celebration of indie films flourishing outside because of IFFI-K is exaggerated. When the same film that is houseful at the festival goes to theatres, no one is watching. Where is the visually literate or cinema literate audience of Kerala then?” said film critic C S Venkiteswaran.

“People outside Kerala have a very microscopic view of Malayalam cinema. They think Malayalam films are only and all about content. That is not true. They still rely heavily on stars,” said an award-winning indie director on condition of anonymity.

Malayalam filmmaker Krishand was on top of the world when his indie film, Aavasavyuham: The Arbit Documentation of an Amphibian Hunt, won the National Award for best film on environment conservation. It also won the Best Film award at the Kerala Film Festival and was soon acquired by Sony Liv. But Krishand insists that his success is more an exception.

Most independent movies never see the light of day after leaving editing rooms, and almost all filmmakers rely on other jobs to support their passion.The kind of celebration of indie films flourishing outside because of IFFI-K is exaggerated. When the same film that is houseful at the festival goes to theatres, no one is watching. Where is the visually literate or cinema literate audience of Kerala then?” said film critic C S Venkiteswaran

B 32 Muthal 44 Vare explores the theme of gender by using breasts as a symbol of sexuality. The KSFDC awarded Sharanyam Rs 3 crore under its ‘Films directed by Women’ scheme so that she could make her film.

She faced no interference from the department. “I had absolute freedom on the film content,” she said. But her gratitude is laced with bitterness as “people did not even get to see it.”

Other indie filmmakers who’ve received support from the government to tell stories that push accepted boundaries have faced similar experiences.

The kind of celebration of indie films flourishing outside because of IFFI-K is exaggerated. When the same film that is houseful at the festival goes to theatres, no one is watching. Where is the visually literate or cinema literate audience of Kerala then?

–Film Critic C S Venkiteswaran

In 2019, Mini IG was one of the first recipients of government money for her feature film, Divorce, which explores adultery, abuse, fraud and other pressure points that cause marriages to crumble. The film was ready three years ago during the Covid-19 pandemic, but it was released only in February this year.

Divorce was hanging in bureaucratic limbo all these years.

“They promised me a date of release multiple times, which would be so specific, like the 15th of a month, that you’d be convinced it would happen,” Mini had told The News Minute.

In 2020-21, the Kerala government announced that it would also fund two filmmakers from the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities as well.

In another move to promote the underrepresented and marginalised, actor Negha Shahin became the first person in the state to receive the 52nd Kerala State Film Award in the transgender category in 2022 for her role in the Malayalam film Antharam.

But there’s been many a slip between intention and implementation.

“How do you really encourage women filmmakers to make more films? That will happen only when more people get to watch their films,” Sharanyam told ThePrint.

Also read: ‘Made in Heaven’ got Indian filmmakers talking caste in US, North-South cinema divide

How innovation fights the low budget

Most directors multitask—they are also screenwriters, editors, and cinematographers. Filmmakers Shinos and Sajas Rahman, better known as the Rahman Brothers, have picked up many money-saving tactics over the years, which they call “guerilla tactics”. They’ve strapped cameras onto actors while shooting in crowded spaces, shot on phone cameras, and, like almost every indie filmmaker, worked with first-time actors. They credit their film literacy to the movies they grew up watching in Aluva.

“I come from an editing background, and my brother Sajas went to the National School of Drama to learn direction in theatre,” said Shinos. Sajas specialised in light design in theatre but ended up working with mainstream directors – a collaboration that lasted for over a decade.

They’ve made three indie films so far: Kalippaattakkaaran/Toymaker (2015), Vasanthi (2021) and Chavittu (2022). But Vasanthi, which won Kerala State Film Awards in three categories, including best film and best original screenplay, never found a commercial release in theatres or streaming platforms.

And that is the fate of many indie films – they may win multiple awards at IFFK and screen to packed halls, but they are ultimately relegated to YouTube.

“Indie films are not necessarily stepping stones to the industry,” said Shinos. Awards and streaming debuts don’t guarantee buyers.

A few, like Lijo Jose Pellissery, have made the transition to mainstream cinema. His 2022 movie, Nanpakal Nerathu Mayakkam, was produced by Mammootty, who also acted in the film.

But his earlier film, Angamaly Diaries (2017), which was made on a Rs 2 crore budget, was a bootstrapped production. It had 86 debutant actors and an 11-minute-long take in the climax featuring a 1,000-strong crowd of non-actors. “The DoP [director of photography] literally fell down once the shot was done,” said Pellissery in a Film Companion video.

Also read: Basil Joseph perfected small-town Kerala stories with global appeal. Next, pan-India success

Few takers between theatre and OTT

Pelisserry cracked the code of making critically and commercially successful indie films with Amen (2013), Angamaly Diaries, Ee.Ma.Yau. (2018), and India’s official entry to the 2019 Oscars, Jallikattu. But he’s more the exception than the norm.

Even the 17 Kerala government-run theatres would prefer commercial films over indie ones, said Venkiteswaran. These theatres mandate a minimum of 10 audience members to run a show.

And independent theatre is hamstrung by the fact that it relies heavily on critics, YouTube reviews and word-of-mouth.

“More the aesthetic value, the harder it is to sell the film,” said Krishand.

Deeply experimental films like Krishnendu Kalesh’s post-pandemic, anti-war dystopia Prappeda or Hawk’s Muffin (2022) did not find an audience in theatres. The film did, however, make it to the Rotterdam Film Festival, where it was screened under the ‘Bright Future’ category.

With cinema houses losing their appeal among moviegoers and screenings becoming limited, OTTs remain their only hope. “But OTTs are no longer buying indie films,” said Venkiteswaran. “Even they want to rely on subscriptions and viewership. So ultimately, they also go for the more commercial films.”

Even a popular streaming platform touted to be the ‘home’ of global indie films, only pays about Rs 35,000 to such movies despite charging an expensive monthly subscription fee of Rs 499, said a director who did not wish to be named.

More the aesthetic value, the harder it is to sell the film,

–Krishand, Malayalam filmmaker

Venkiteswaran argues that the internet has actually ruined viewing culture, especially when it comes to non-mainstream cinema.

Not everyone agrees with this assertion, though. Kalesh, whose movie looks at the interaction of nature and technology, is curious about what tech can achieve in the film industry.

“As digital innovation emerges, artists think anthropologically, and its nature is symbolic. More than mere reproduction or recreation, deconstruction and reinterpretation take place,” he said.

Kalesh is comfortable with the knowledge that his film is not meant to be comprehended in a single viewing. He made it for OTT, where one can keep going back to the movie and decode it in multiple viewings.

“In the future, I would like to look at the movies that are born using AI from the same position.”

Also read: London, NYC, Taiwan—Bengali filmmaker a toast of the world. But he’s all about power of local

Big names still sell

Even in low-budget commercial films, stars play a key role in success and failure. Actor Lukman Avaran’s presence in Tharun Moorthy’s 2021 Debut film Operation Java helped catapult it to success. And not only did it get rave reviews, but it also made roughly Rs 3.6 crore worldwide.

Made on a budget of Rs 1.5 crore, the movie, which tackled cybercrime and unemployment in Kerala, was acquired by Zee 5 after a successful box office run.

“I have always wanted to be a director, but I knew I had to have some backup before making a film,” said Moorthy, a self-taught filmmaker. He built a career in ad making while nurturing his dreams of making a feature film.

But despite his success, he had to struggle to make his second film, Saudi Vellakka (2022).

Instead of roping in a well-known face, he took the bold step of casting 75-year-old first-time actor Devi Varma to play the character of Ayisha Rawther. Furthermore, despite repeated warnings from industry insiders, he cast 50 new actors for his film.

It was a risk that almost cost Moorthy the theatrical run of his movie.

“We had to call up people to request them to turn up for shows. It was only after some YouTuber gave it a good review that people actually started turning up for shows,” said Moorthy.

Cinematographer Joseph wants Kerala’s stars to promote indie films. “Big stars like Nayanthara and Parvathy have relentlessly promoted independent films in Tamil to create visibility. It can also be done in the Malayalam industry,” he said.

The involvement of stars, if not in the film itself but in its marketing or presentation, also makes crowdfunding easier. “It has to be an ecosystem of lifting up indie filmmakers. Only then can we continue to make cinema that pushes boundaries.”

We had to call up people to request them to turn up for shows. It was only after some YouTuber gave it a good review that people actually started turning up for shows

— Tharun Moorthy, writer and director

Also read: SRK changed from Pathaan to Jawan. It shows North-South divide in patriotic action films

Indie films and community support

What keeps Kerala’s indie film industry going is the state’s history of film societies. In this South Indian state, movies stand on the shoulders of the community. There’s a film society in every town and district run by activists and film enthusiasts voluntarily. Around 125 film societies continue to thrive in the state, with some running from the past 50 years.

It was prominent director, scriptwriter and producer Adoor Gopalakrishnan who started Kerala’s first film society, Chitralekha, in Thiruvananthapuram in 1965. The latest one was launched by Women in Collective Cinema, and is named after PK Rosy, Malayalam cinema’s first leading lady.

“Kerala has robust cinema literacy, and indie filmmakers live to make cinema,” said Joseph, who along with a few others, formed Minimal Cinema in Kozhikode, which hosts its own film festival and supports independent and experimental movies in their production and screening.

“Independent cinema always leads the way. Film societies stand for such cinema, which is experimental in all aspects and revolutionises the theme and narrative. In the long run, such offbeat films make and change the history of cinema,” said GP Ramachandran, award-winning film critic and former treasurer of Kerala State Chalachitra Academy.

When imagination is given free rein, indie films have the power to become the new mainstream.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey, Theres Sudeep and Zoya Bhatti)