Jaipur: Ankit Kumar’s house is just a few hundred metres from the Jaipur-Sambhar highway. But that doesn’t automatically mean it is the most prized land in the area.

Last August, 30-year-old Kumar received a call on his smartphone from a private bank. He was offered a loan to set up a polyhouse, a plastic-covered structure for farming. But his smile vanished as quickly as it appeared. Upon learning that Kumar lived in a Gramdan village, the bank official hastily withdrew the offer. In villages like Kumar’s, which comes under Khejdawas Panchayat of Jobner tehsil, 35 km from Jaipur, land isn’t owned by individuals. It’s community property overseen by the gram sabha, or village council.

What began as an ambitious social revolution in the 1950s by way of gramdan (donating land for the benefit of the entire village) under Vinoba Bhave is today nothing short of a curse for the villagers. There are over 200 Gramdan villages in Rajasthan and the system has emerged as a stubborn obstacle in the 21st-century quest for economic aspiration and growth.

“I received more than half the funds for setting up the polyhouse through a government subsidy, but a loan was required for the rest. It was refused as the land documents were not in my name. I couldn’t get a loan because I live in a Gramdan village,” said Kumar.

Vinobha Bhave came to Rajasthan on 15 February 1959 for his padyatra with the goal of persuading rich landlords to donate some of their surplus land to the gram sabha for use by the landless villagers. By the end of the 76-day visit, he received land donations from 171 villages. And individual ownership on this land ceased.

What happened during that visit still haunts Ankit Kumar’s life—because the land is not in his name even though his family has been living there and cultivating it for decades.

Kumar has built his polyhouse, where he’s now growing cucumbers, but to do so he was forced to borrow money from private moneylenders at nearly double the interest rate offered by banks.

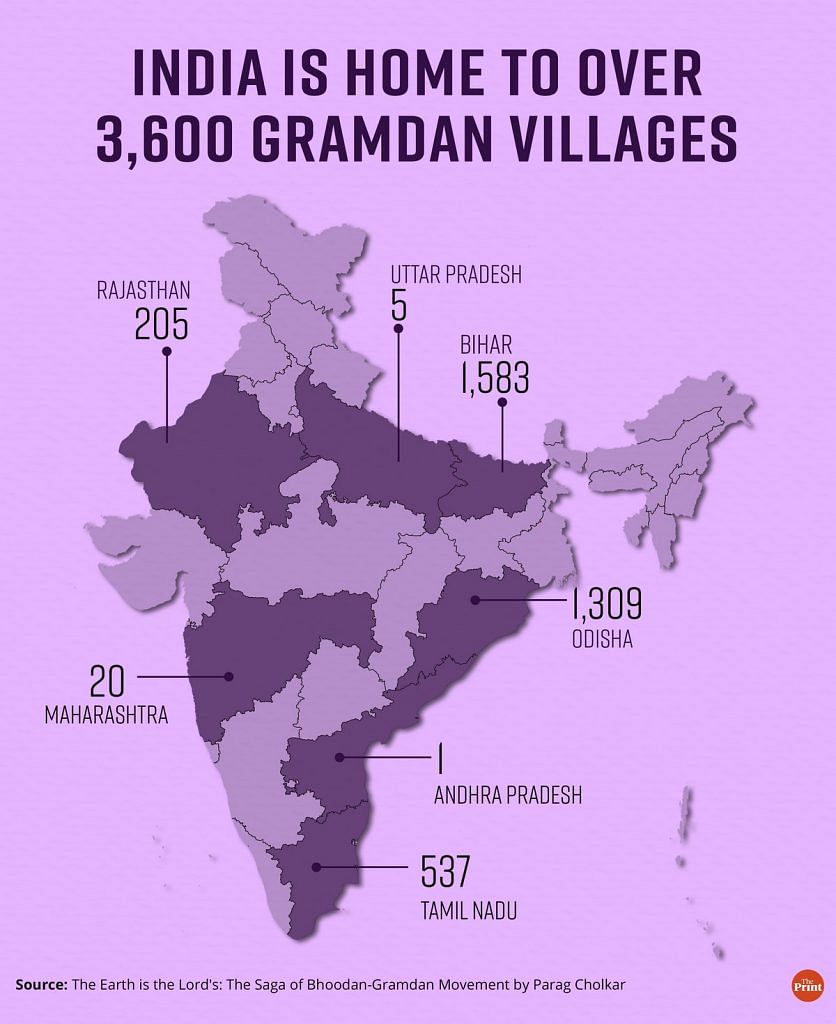

People like Kumar are not landless but they don’t have a single piece of land to their name. Over 3,600 villages in India still operate under the Gramdan system.

The last village in Rajasthan to become a Gramdan was Jaisalmer district’s Bhairava in 2003. Now, people are looking for ways to get out of the system.

The original Gramdan generation is either gone or too old to carry the torch. And younger inheritors never fully bought in. As times changed, cracks started to show.

“The Gramdan work gradually became lax and people started facing problems. Gramdan institutions and the people associated with it did not work properly. Now people want to abolish this law so that ownership of land can become individual,” said Avadh Prasad, author of Rajasthan me Gramdan and director of Kumarappa Gram Swaraj Sansthan, a Jaipur-based NGO focused on rural development. “Gramdan is an emotional work and now due to changing sentiments, the idea is fading away.”

Vinoba Bhave’s socialism experiment has become a noose for the current generation of Gramdan villages in Rajasthan. And to break free, some villages have even formed Sangharsh Samitis.

Also Read: Vinoba Bhave, the Walking Saint who ‘talked’ bandits of Madhya Pradesh into surrendering

Souring of a land ‘revolution’

A famous slogan of the Gramdan Movement captures Vinoba Bhave’s philosophy: “Sabai bhoomi Gopal ki, nahi kisi ki maliki” (All the land belongs to God, no one is the owner of it). The Gandhian reformer, who opposed the private ownership of the land, considered Gramdan to be more powerful than atomic energy. “While an atomic explosion pollutes the environment of the world, a single gramdan purifies the environment of the world,” he said. The concept seemed radical, transformative, with even the American journalist Louis Fischer apparently observing that Gramdan was the “most creative thought coming from the East in recent times”.

It all started in 1951 with Vinoba’s Bhoodan movement to convince landowners to “gift” some of their land to the landless, and then widened in scope to encompass Gramdan, where entire villages donated land for collective ownership. For this cause, Vinoba travelled on foot for 14 years across different states of the country and even in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

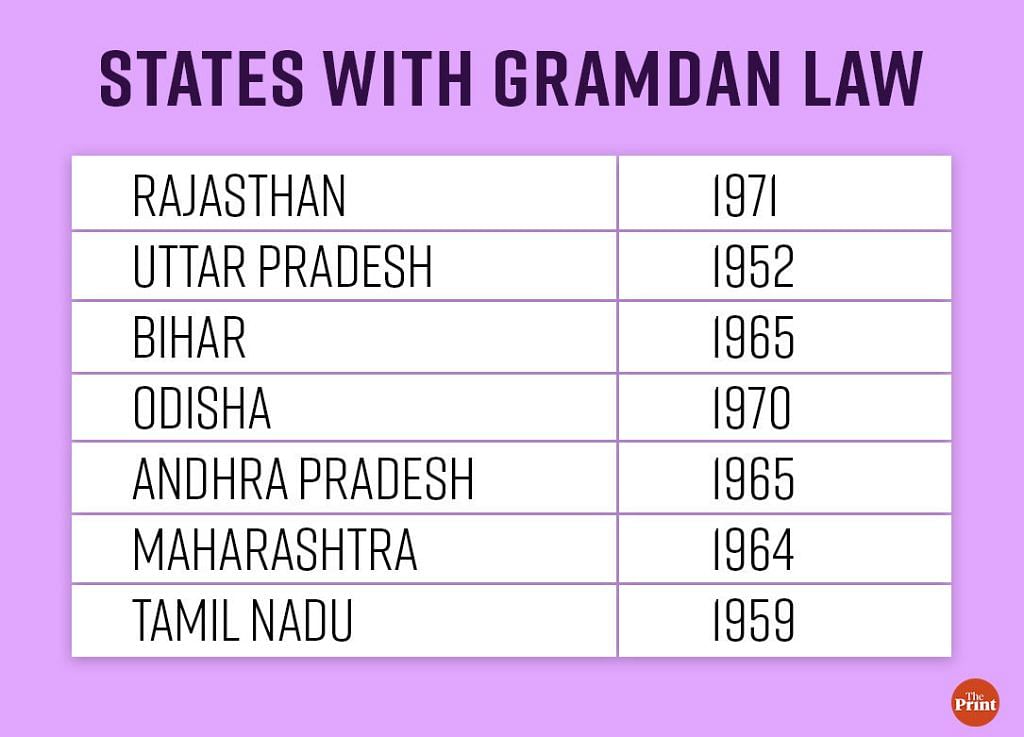

The movement was widely applauded as a land reform revolution. Many states even introduced Bhoodan and Gramdan Acts to facilitate the donation and distribution of land, including Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Bihar, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Assam among others. Under most Gramdan laws, 75 per cent of landowners must surrender at least 60 per cent of their land. In Rajasthan, however, 51 per cent of landowners donating their land suffices. Donors and their descendants retain the right to cultivate the land, but selling it outside the village is prohibited.

Earlier, we used to consider Gramdan as a very sacred thing, but we cannot use the land commercially and farming is not the same as before. We also have to join the stream of development, but Gramdan has blocked these possibilities.

-Rajendra Kumar, a 28-year-old farmer from Khejdawas

But the movement always had vocal critics, such as farmer leaders Chaudhary Charan Singh and NG Ranga. The latter, in particular, vehemently denounced it, arguing that it would lead to forced collectivisation of land and undermine individual liberty.

Over the years, activists have also alleged that governments are using Bhoodan land for development projects, and that powerful people collude with corrupt officials to acquire this property. Despite these concerns, the Bhoodan and Gramdan Acts remain in force in several states, although Assam, which had 312 Gramdan villages, repealed its legislation in 2022 to combat encroachment and illegal transfers.

Now, in Rajasthan, rumbles of protest are growing from the villagers themselves. Vinoba’s socialism experiment has become a noose for the current generation of Gramdan villages. And to break free, some villages have even formed Sangharsh Samitis (struggle committees).

One such committee came up in Jaipur district Jobner tehsil in 2022 and another in Dungarpur this January.

All the 10 Gramdan villages in Jobner—six in Khejdawas panchayat and four in Aydan Ka Bas—came under this system between 1955 and 1965, and all want out.

Jeevan Ram, the 75-year-old president of the Khejdawas Gramdan, recalled being only 12 or 13 years old when Vinoba Bhave arrived in 1960. “Vinoba ji held a meeting in the village and explained the benefits of gramdan to the people. The villagers accepted his words and joined,” he said. “It was a good thing at that time, but rising aspirations have made the new generation disillusioned with it.”

Liberation from lofty ideals

One of the walls in the Panchayat building of Khejdawas village, home to around 1,500 residents, displays the message: “Gaon ko chokho gaon banaye” (Make the village a good place). But the people here say that the Gramdan tag is not allowing it to become chokho.

Jaipur’s growing urban sprawl is inching closer to hinterlands such as Jobner, bringing with it both opportunity and frustration. Villagers living along the highway have started many types of businesses, but residents of Gramdan villages are stuck on the sidelines. They are not allowed to use communal land for commercial purposes. If they do, they risk losing lease of their land received from the gram sabha.

“Earlier, we used to consider Gramdan as a very sacred thing, but we cannot use the land commercially and farming is not the same as before. We also have to join the stream of development, but Gramdan has blocked these possibilities,” said Rajendra Kumar, a 28-year-old farmer from Khejdawas.

The villagers are trapped. They have land, but it’s not theirs. They are locked out of government schemes that could uplift their lives and they can’t pick up and leave easily either.

In the 10 Gramdan villages of Jobner tehsil, very few farmers are getting the benefit of the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana. They don’t get compensation if their crops are affected, banks don’t give them Kisan Credit Cards and loans, and obtaining seeds and fertilisers from the government is a hassle.

Rural youth see selling their land as the key to achieving their dreams of a modern lifestyle, but this option is out, Prasad pointed out. “The government is also indifferent towards these villages,” he said.

People are also paying a social cost of the failed revolution. Gramdan villagers said no one wants to marry their daughters as land ownership is not private.

Villagers want liberation, Prasad said. They simply want to live like others, with the freedom to pursue their dreams and enjoy basic rights. Lofty ideals aren’t enough to sustain them.

This is something that even Gandhian scholar Parag Cholkar touched upon in his 2017 book The Earth is the Lord’s. “The effort was not just for abolition of private property in land, it was for total transformation in man and society. Higher the aim, more are the chances of failure,” he wrote. “The Bhoodan-Gramdan Movement preferred to risk failure instead of having a lower aim.”

Villagers allege that the Gramdan system resembles a fiefdom, with the gram sabha president controlling all land, records, and lacking accountability to the people.

Unchecked powers, corruption

When Gopal Bana’s father surrendered his land in 1955, the atmosphere was charged with noble intentions and soaring hopes. The donors, Bana said, anticipated their land remaining effectively theirs, with a portion distributed to the landless. They envisioned their village, Joshiwas under Khejdawas panchayat, enjoying greater autonomy—a mini-republic of sorts. The idea was that land and personal disputes would be handled collectively and they would not need to travel to the tehsil for paperwork. All records would be maintained at the village level by the gram sabha president.

But Bana, who is in his 40s, finds himself reaping a bitter harvest. Banks have rejected his loan applications for his children’s higher education, forcing him to rely on predatory moneylenders. And instead of autonomy, the gram sabha president has morphed into an unchecked power centre, giving rise to corrupt practices. “We are totally dependent on the gram sabha president for everything for our work,” Bana lamented. “They are not ready to do any work without taking money.”

Gramdan is not the same today as it was earlier. It hurts to see the campaign started by Vinoba ji in this form

-Rambabu Sharma, Rajasthan Bhoodan-Gramdan Board official

In Khejdawas, president Jeevan Ram’s term ended on 21 February, and a successor is yet to be chosen. He denies any wrongdoing but acknowledges that such issues are prevalent elsewhere.

Villagers allege that the Gramdan system resembles a fiefdom, with the president controlling all land, records, and lacking accountability to the people. And under the Gramdan law, the president has the authority to make unilateral decisions for the village.

When it comes to selling land, the only avenue is through the president, who acts as a middleman and takes a cut, villagers allege. Moreover, since the land is not included in government revenue records, its value plummets. Rajendra Kumar of Khejadwas recounted that a plot near his house was sold for Rs 20 lakh, whereas similar land in an adjacent village fetched Rs 1 crore. “The land prices are low because our village is Gramdani. We have to bear such a huge loss,” he said.

While selling land to outsiders is prohibited, gram sabha presidents fraudulently circumvent this rule by adding buyers’ names to the village voter list, and then profit from the sale, according to Sohan Sepat, sarpanch of Khejdawas Panchayat. The system has become a “money-making tool”, he said.

Such is the overhang of Vinobha Bhave’s movement that successive BJP and Congress governments in Rajasthan have hesitated to repeal the Gramdan Act.

Several corruption cases have emerged against the presidents of Rajasthan’s Gramdans in recent years. For example, in 2018, authorities booked six people, including the president of a Gramdan village in Khajuriya village, Dungarpur, for land sale fraud. That same year, a tehsildar in Makrana, Rajasthan, filed a case against the president of Kalwa Chhota Gramdan village for misusing his position by refusing to provide land records.

Although the gram sabha president must be elected unanimously by the people every three years, there are frequent delays. Often, presidents remain in office indefinitely by default, compounding the issue of lacking accountability. In some villages where Gramdan presidents have died, their sons are handling the records related to the land.

Even Rambabu Sharma, a veteran with 45 years of experience at Rajasthan’s Bhoodan-Gramdan Board, is disillusioned.

“Gramdan is not the same today as it was earlier. It hurts to see the campaign started by Vinoba ji in this form,” said Sharma, seated on a wooden chair amid dusty files in the dilapidated Gramdan Board office in Jaipur, opposite the Old Vidhan Sabha near Hawa Mahal. “So many cases of Gramdan villages are pending in the High Court today. The purpose of Gramdan villages was that people would solve their issues by sitting among themselves. But when the cases are going to the court, then what is the meaning of Gramdan?”

Ruefully, Sharma conceded that Gramdan is a system whose time has passed. “We are living in a materialistic era. People fulfill their dreams by selling their lands. When their lands will not be sold due to an old law, it is natural that people will feel uncomfortable,” he said.

Although the revenue records of most of the state’s 44,672 villages are available online, the same cannot be said for the 205 Gramdans scattered across various districts.

A growing fight & some victories

Over the past two decades, villagers have repeatedly approached MLAs, MPs, and ministers about the problems plaguing Gramdan villages. But such is the overhang of Vinobha Bhave’s movement that successive BJP and Congress governments in the state have hesitated to repeal the Gramdan Act.

“Vinoba Bhave’s image is that of a great social reformer of India, and he is respected like a saint. No government wants to completely end the campaign started by him. However, at its core, it has been becoming weak over the years, said a senior official of the Revenue Department of Rajasthan on the condition of anonymity. “Gramdan is now reduced to just a name.”

During the movement’s peak in 1969, the reported number of such villages stood at 137,208, although far fewer are currently recognised. “Gramdan was more an emotional action than a legal one,” clarified Avadh Prasad. “Therefore, the number of Gramdan villages was very high, but only a few of them were approved under the law.”

Even today, a certain opacity lingers around Gramdan villages in Rajasthan. Although the revenue records of most of the state’s 44,672 villages are available online, the same cannot be said for the 205 Gramdans scattered across various districts, including Jaipur, Udaipur, Chittorgarh, Nagaur, Jaisalmer, Tonk, Dungarpur, Banswara, Bhilwara, Sikar, Sirohi, and Baran.

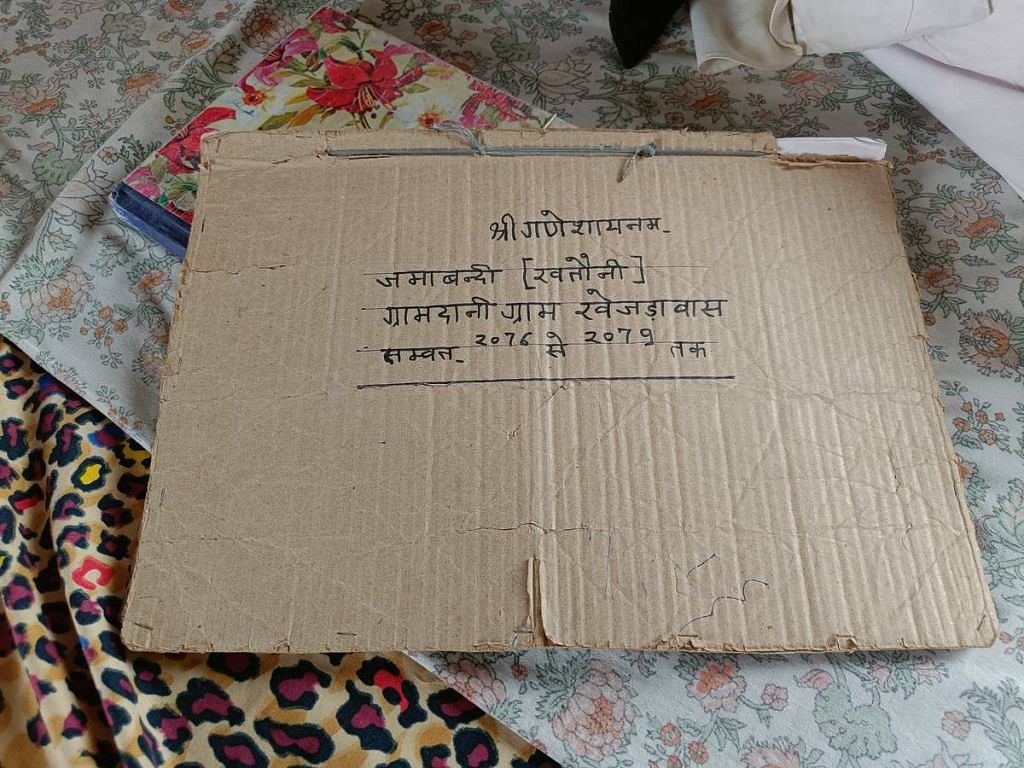

For these villages, all such information is confined to thick registers kept under lock and key by gram sabha presidents.

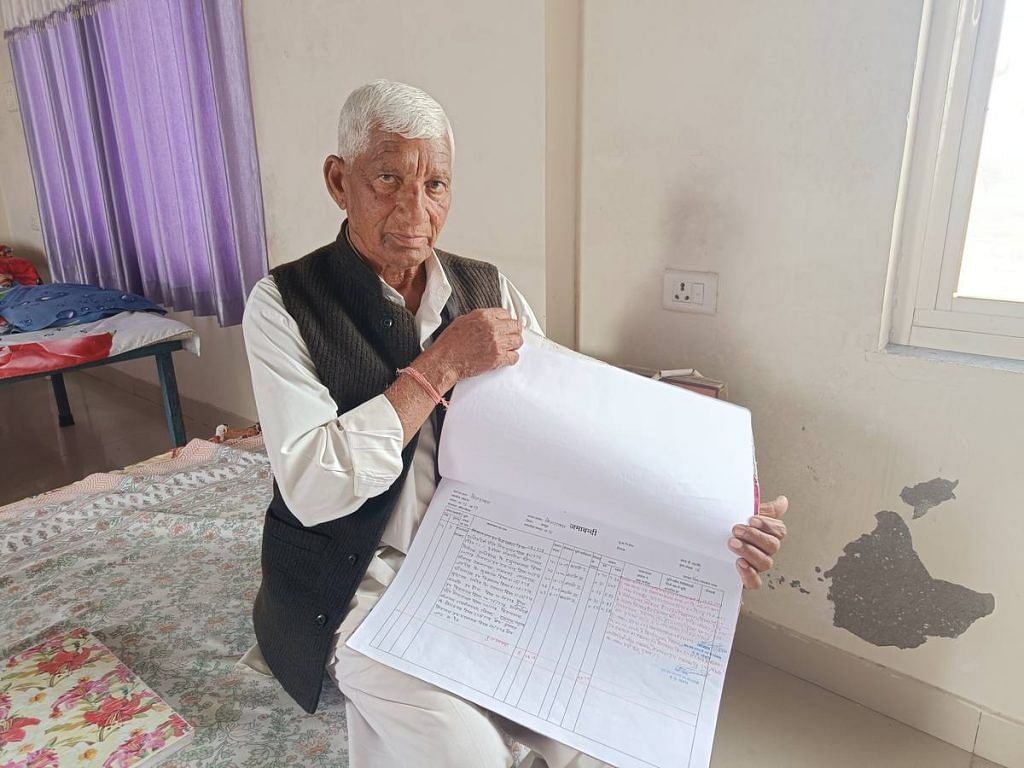

In Khejdawas, the de facto Gramdan president Jeevan Ram maintains a register containing allotment data for the village’s 193 bighas of land. “It contains the information of the entire village and the land related data of every family. The revenue department of the district does not have the data of our village,” he said, as he pulled out the register from an almirah on the first floor of his house.

Many residents want the status quo to change. The Gramdani Hatao Sangharsh Samiti advocates for online land records in Gramdan villages. They argue that the lack of online access facilitates fraudulent land sales by Gramdan presidents.

We are having to pay the price for the mistakes our ancestors committed

-Devnarayan Bairwa, Jaiprakashpura resident

“Problems started after 1980,” said samiti member Sepat, showing letters he sent to local representatives. “Gramdan presidents started prioritising their personal benefit and began allocating more and more land to their relatives, which is against the basic spirit of the Gramdan law.”

Local newspaper headlines capture the prevailing sentiment in these villages: “Yahan sarkar ki bhi nahi chalti panchayati (Even the government doesn’t run the panchayat here); “Yahan sirf tanashahi aur manmani “ (Dictatorship and arbitrariness reign); “Gale ki faans bana gramdan act (The Gramdan Act has become a noose around the neck); and “Hame nahi rahna gramdani gaon mein” (We don’t want to live in a Gramdan village).

However, in 2022, the Sangharsh Samiti achieved a small victory. The residents of Balolai village in Aaydan ka Bas Panchayat, through the Sangharsh Samiti, declared their withdrawal from the system under Section 37(a) of the Rajasthan Gramdan Act. By voting, they successfully opted out with a majority.

But changes are yet to be seen on the ground. “Even after voting, it has not been included in the revenue system yet,” said Sepat. “No one pays attention to these villages. There are only assurances from the officials but no action is taken.”

But the rebellion against the Gramdan system seems to be spreading. In January, all 41 Gramdan villages in Dungarpur district came together to form their own Sangharsh Samiti. They have held four meetings at the district headquarters and formed village-level committees in 22 villages so far.

The residents of these predominantly tribal villages have also approached Aspur MLA Umesh Meena, a leader of the Bharat Adivasi Party, to exert pressure on the administration.

Meena told ThePrint that most of these villages haven’t held elections for the post of Gram Sabha president since 2005 and that the district magistrate ignores their concerns because they are not revenue villages. “Jamabandi registers (land records) are not being maintained properly in accordance with the Gramdan Act,” he added.

This issue is getting political traction elsewhere as well. In the 2023 Rajasthan elections, Suresh Modi, Congress MLA from Neem ka Thana, included “freedom from Gramdan” in his 23-point election vision. Out of the 16 Gramdan villages in Neem ka Thana, four have already transitioned out of the system, but 12 are still waiting despite completing the voting process. “Everyday people come to me with complaints,” said Suresh Modi, who also raised this issue in the Assembly on 12 July 2023.

Also Read: Gujarati Muslims struggle to buy Hindu property. Disturbed Areas law weaponises real estate

Two sides of the coin

Not everyone wants out of the Gramdan system. Some even want in.

Mendha, a primarily Gond tribal village in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra, struggled for a decade to join the Gramdan system. It also sought separation from its governing panchayat, Lekha. This year, their perseverance paid off. The Maharashtra government granted Mendha separate Gram Panchayat status under the Maharashtra Gramdan Act of 1964, recognising their 500-strong population as a distinct village unit.

The quest of these residents started in 2013, when they unanimously voted to become a Gramdan and contribute their land to the gram sabha. However, the state revenue department initially denied them independent panchayat status, prompting them to seek recourse in the Nagpur Bench of the Bombay High Court. For these villagers, Gramdan status reportedly signified “self-rule and sovereignty over their forests and land”.

But in Jaipur’s Jaiprakashpura village, the Gramdan land scheme has led to ghost lanes of empty homes.

Established as a Gramdan village in the 1960s by socialist leader Jayaprakash Narayan, it’s now crumbling, with decaying walls and barren fields. Those who do live here struggle to make a living, such as Devnarayan Bairwa, who travels 60 km daily to Jaipur for daily wage work.

“Our ancestors made their living by farming but it’s not feasible for the new generation. Due to water scarcity, farming is not profitable here. In such a situation, we have to spend Rs 150 per day and go to Jaipur to work as labourers, he said. “We are having to pay the price for the mistakes our ancestors committed.”

The population of Jaiprakashpura is officially 500 but most people have migrated long ago, leaving locks hanging on the doors of dozens of houses on Gramdan land.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

So what is the alternative to Capitalism?

Socialists think they are ‘intellectuals’, and that their IQ is more than 200. If not for the socialist curse, India would have become a developed country decades ago.