Vadodara/Ahmedabad: Three little hijab-clad girls, barely 10 years old, skip into Laiyakat Alibhai Patel’s shop to buy a second-hand cycle. An invisible line bisects the lane where this shop sits, marking the start of the Muslim quarter in Vadodara’s Tandalja. The bare-bones shop sits just behind an upper middle-class, predominantly Hindu neighbourhood. Indian cricketer Irfan Pathan’s palatial white family home and a row of government-built EWS flats stand at the colony’s edge.

These carefully constructed spaces tell a story of spatial segregation that has been deepening organically and also through written and unwritten social codes in Gujarat.

In the seemingly tranquil neighbourhood of Tandalja, the two communities coexist, yet lead parallel lives. Two months ago, this delicate balance received a jolt when five Hindus lost their legal fight against the sale of a home to a Muslim. A property transaction between people of different religions isn’t simple in Gujarat. It can turn into a tinderbox.

The tension began in 2019 when Hindu businesswoman Geeta Goradia sold her upscale bungalow in Tandalja’s Kesarbaug Society for Rs 6 crore to Muslim businessman and educationist Faisal Fazlani.

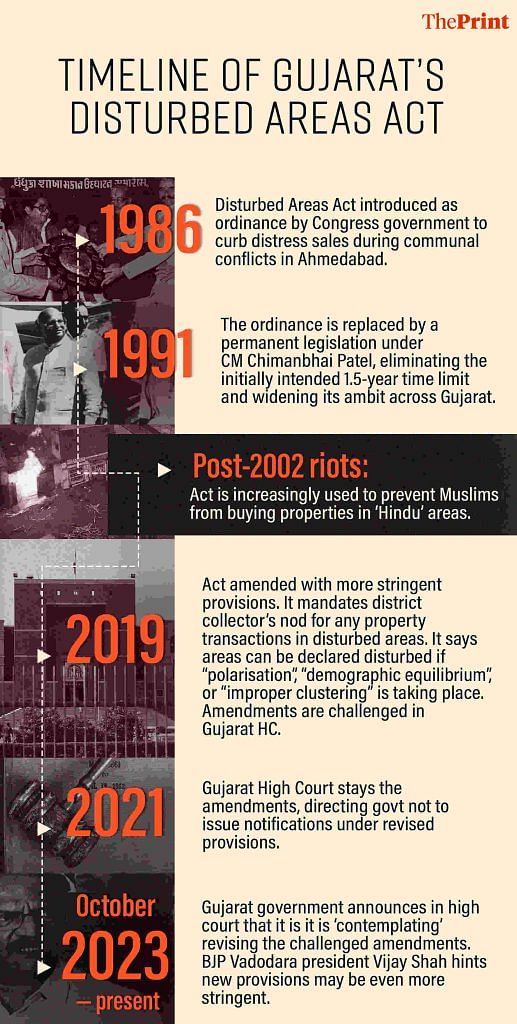

A unique three-decade-old state law mandates that property deals must be approved by the district collector in areas marked as “disturbed”, and while it does not expressly mention religion, it is usually invoked in cases of Muslim-Hindu transactions.

It is this law, the Gujarat Prohibition of Transfer of Immovable Property and Provision for Protection of Tenants from Eviction from Premises in Disturbed Areas Act—or just the Disturbed Areas Act—that became the battleground for five Hindu neighbours after the sale.

Objecting to the Goradia-Fazlani deal before the district collector, they contended that such a transaction could not be done until each immediate neighbour agreed to it. They also raised concerns about bogus documents and potential “law and order” issues in Kesarbaug Society. The ensuing legal battle stretched for four years, with the neighbours even approaching then chief minister Vijay Rupani. Finally, in November 2023, the Gujarat High Court upheld the sale, ruling that the goal of the Disturbed Areas Act is to not to assess fears of law-and-order deterioration but to decide if it is a distress sale.

(The law is being used) to restrict Muslims to certain areas and make them systematically marginalised. And if communities don’t interact, it’s going to affect the future of society in terms of ideas, mindset, and openness

-Sharik Laliwala, PhD scholar

This legal battle, however, is just one among many related to the Disturbed Areas Act that have landed in court. Over time, as the law got weaponised amid fraught Hindu-Muslim ties, it has faced legal challenges. An Ahmedabad-based lawyer claimed that his law firm alone is handling 30 such cases in the Gujarat High Court, most filed after the state government made the law more stringent in 2019.

Over three decades, cases under the Act were invariably settled in favour of upholding the inter-religious sale, but the amendment armed the district collector with more power. Anyone could stall a property sale if they cited “disturbance in demographic equilibrium”, “improper clustering of persons of a community”, or “likelihood of polarisation”. While the high court stayed the amendments in 2021 and ordered the state government not to issue notifications under it, the Disturbed Areas Act continues to cast a shadow.

The legislation, enacted by the Chimanbhai Patel-led Congress government in 1991, was initially intended to curb distress sales triggered by communal riots. But in Gujarat, where religious polarisation runs deep, it has transformed into a tool for the state to regulate property purchase between communities.

A 2022 Urban Studies paper pointed out that instead of protecting against “spatial segregation and ghettoisation”, as was its original purpose, the law was deployed to perpetuate it.

Some even compare this to the racial restrictive covenants in property buying that were once used to enforce segregation in the United States.

However, Vadodara BJP president Vijay Shah said he saw no contradiction in the way the Disturbed Areas Act was being used, arguing that it served the ultimate goal of “social harmony”. He claimed that one key reason for its statewide enactment was to prevent social discord caused by close proximity between different communities.

“It was noticed by many residents that the next-door neighbour comes from a community they are not comfortable with because of the cultural difference, food habits, the number of people in the houses, and the way they live,” he claimed. “This is one of the reasons why the government thought of this Act.”

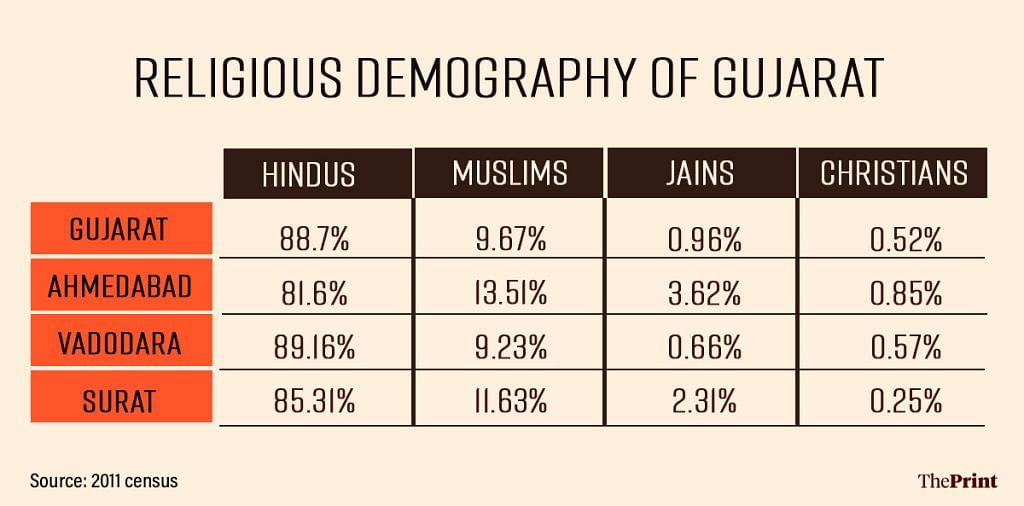

The Act is currently in force in large swathes of the state’s three major cities: Ahmedabad, Vadodara, and Surat. It also extends to several smaller towns and cities.

Also Read: Bilkis Bano rape convicts not missing, in ‘deep introspection’, say families

‘Noble’ intentions, opposite effect

The mid-1980s were a turbulent time for Gujarat. As Hindu-Muslim riots escalated and the BJP gained ground in municipal elections, new anxieties and fears permeated neighbourhoods. In Ahmedabad, especially, communal conflicts reached a boiling point in 1986, leading to exoduses from certain neighbourhoods and panicked property sales. It was in this environment that the Congress government, under Chief Minister Amarsinh Chaudhary, introduced the Disturbed Areas Ordinance in 1986.

The purpose behind it was “noble and laudable” according to an Ahmedabad-based lawyer—arresting the trend of communal segregation of neighbourhoods by keeping a check on distress sales. The ordinance mandated that the district collector would act as a gatekeeper for every sale in a “disturbed area”, ensuring that transactions occurred with free consent, without coercion, and at fair market value. The government could designate areas as disturbed based on observed internal migration or instances of rioting or mob violence.

“This phenomenon of people leaving and areas being claimed by one particular community shouldn’t happen,” the lawyer said, sitting in a law chamber on the posh Iscon-Ambli Road. “This legislation was brought in to stop it, so that the collector could check that people were not leaving just out of fear or coercion.”

Conceived as a temporary measure for just 1.5 years, the ordinance’s trajectory shifted in 1991, when it was enacted as a law under CM Chimanbhai Patel—just a few months after the conclusion of the Ram Rath Yatra, which had started from Somnath in Gujarat. This revision eliminated the fixed time period, granting the government discretionary power to implement the Act whenever it deemed fit.

The Act is currently in force in large swathes of the state’s three major cities: Ahmedabad, Vadodara, and Surat. It also applies to smaller towns and cities like Bharuch, Kapadvanj, Godhra, Anand, and others. Savarkundla in Amreli district became the latest area to come under its purview last July.

While the law’s text makes no mention of religion, focusing solely on “riot” and “violence of mob,” its application has always been along religious lines. But it was largely in the aftermath of the 2002 riots that its use started changing.

Assimilation in the area is not possible because it has already been ghettoised. It has reached a level that a Hindu would be really sceptical in buying a business or residential property here

-Hitarth Pandya, educator & former journalist

The first five years after the riots saw large numbers of Muslims seeking refuge in existing ghettos like Juhapura and Tandalja, away from the posh areas of big cities like Ahmedabad and Vadodara, according to Sharik Laliwala, a PhD scholar in political science at the University of California, Berkeley.

Later, as the dust settled, the Disturbed Areas Act was used to stifle the mobility of Muslims seeking to move to better neighbourhoods, which tend to have more Hindu residents. This, in turn, exacerbated the issue of Muslim ghettoisation.

“(The law is being used) to restrict Muslims to certain areas and make them systematically marginalised,” Laliwala said. “And if communities don’t interact, it’s going to affect the future of society in terms of ideas, mindset, and openness.”

Multilayered modus operandi

To close an inter-religious sale even in the same city means navigating an obstacle course comprising angry neighbours, nervous sellers, the district collector, police, and the courts.

The lawyer, who has extensive experience with cases under the purview of Disturbed Areas Act, outlined a recurrent pattern of misuse.

“If a Muslim wants to buy a plot and set up a flat, the collector might object to it at the permission level. The collector might say this transaction would cause a disturbance, upset the demographic equilibrium, lead to a law-and-order situation and so I’m not permitting it. He would do it using the Act,” the lawyer said.

In such a scenario, the aspiring buyer must approach the court and argue that the collector’s considerations should be limited to the free consent of the seller and if the transaction is for fair market value. Relief is usually granted by the high court in these cases, but then neighbours may create trouble.

Although the law does not specify that neighbours’ concerns should be taken into account, they often get an official hearing.

“If you (a collector) want to slow down a transaction and create circumstances for it to somehow fail, then you would entertain their application, hear the neighbours,” the lawyer said.

Despite several high court judgments ruling that neighbours don’t have any locus standi in property sales, this trend persists. Last February, for instance, the Gujarat HC fined two groups Rs 25,000 for seeking the review of an order permitting the transfer of a shop from a Hindu to a Muslim in Vadodara.

Until and unless you go through the situation, you can probably never understand how difficult it is to live with a community you are not comfortable with. And it’s not specifically about religion, it could be anything

-Vijay Shah, Vadodara BJP president

The police are the next line of ‘defence’. If someone files an application stating that the deal is dubious in some way, collectors at times approach the police who then conduct an enquiry in the neighbourhood. There have been occasions when collectors themselves have sought the “opinion” of the police on whether a sale might affect law and order, the lawyer added. If the police ascertain that this is indeed a concern, the collector is empowered to deny permission for the deal to be completed.

Despite all of this, many Muslims seek to stay in central and better developed ‘Hindu’ areas. And the wealthy among them are ready to pay a “much higher price” than Hindus, according to Laliwala. “Because of a fairly limited supply for the elites and upper classes, they are often willing to pay a premium,” he said.

Bad for the real estate business

The discriminatory nature of the law disrupts even interfaith business partnerships. A Vadodara-based Hindu real estate developer, who has built 11 buildings near the disputed Tandalja bungalow, recounted dissolving his partnership with a Muslim colleague. Their joint venture on the Muslim builder’s land hit a snag when selling the flats.

“Buyers were reluctant to purchase flats when they saw a Muslim developer was involved, or when they saw his name on the documents,” the Hindu builder said. Eventually, the registration papers were changed to feature only the name of the Hindu builder.

Despite claiming to maintain a personal friendship with his former partner, the Hindu developer expressed apprehension about mixing business and religion. “Our business is to sell houses. But it’s better for both communities not to mix because their food habits and lifestyles are different,” he said.

Another problem is delays caused by increased scrutiny of paperwork in “H-M” or “M-H” (Hindu-Muslim or Muslim-Hindu) dealings.

“When it’s a Hindu-Muslim transaction, the sale deed is not made even after a year, when it should be a matter of weeks. Even Hindus are not able to sell their property because of the law,” said a seasoned Muslim builder in Ahmedabad who specialises in redevelopment projects.

Echoing this, a prominent Hindu property developer in Ahmedabad complained that sometimes the registration process of “H-M” sales deals can drag on for 4 to 5 years. “The Act doesn’t affect the price or the sale of property but it does affect the speed and comfort of the buyers,” he said.

Muslim builders feel the brunt of the Act’s limitations, often restricting themselves to Muslim localities to avoid legal complications, even if it means sacrificing lucrative projects. “We are asked to build in Hindu pockets but we refuse,” the Muslim builder said.

Yet even in the real estate business, the law is seen as a necessary inconvenience.

The Ahmedabad-based Hindu builder, while complaining about the hassles of compliance, defended the law’s role in maintaining “smooth” functioning in Gujarat. He suggested keeping the law for individual transactions but exempting builders, arguing that “forced” sales aren’t an issue in their case.

Vasna Road boasts fancy clothing showrooms, electric shops, and cafes, but Tandalja Road just behind it, home to Patel’s humble cycle shop, is a different world.

Fear and fury

The outcry over the bungalow sale between Goradia and Fazlani exemplifies the strong resistance to even the slightest blurring of communal lines in ‘Hindu’ neighbourhoods.

The sprawling single-storey bungalow on Tandalja-Vasna Road sits a hair’s breadth from the Muslim ghetto, but there is an almost impassable chasm between them.

Vasna Road boasts fancy clothing showrooms, electric shops, and cafes, but Tandalja Road just behind it, home to Patel’s humble cycle shop, is a different world. This narrow lane serves as the crude intangible border marking the physical divide between the two communities.

It’s an uneasy coexistence that passes for communal harmony. “Hindus and Muslims live harmoniously here. There is a Hindu shopkeeper a few shops away from mine. We have a Hindu doctor who runs his clinic just behind this area. We have a Christian-run school too,” said Patel, citing instances of diversity in his otherwise single-religion neighbourhood.

In the affluent Hindu enclave nearby, nestled between Vasna and Tandalja roads, resides Patel’s childhood friend, Hitarth Pandya, whom he addresses as ‘sahib’.

A journalist-turned-educator, Pandya defied warnings from friends and family about living near a “Muslim-dominated area” to buy the property in the early 2000s. This was the period during which the demographic composition of Vadodara’s localities had just started changing.

Due to the riots in Vadodara’s Old City in 2002, many Muslims migrated from mixed neighbourhoods to seek safety in numbers in Tandalja. “It’s colloquially known as mini-Pakistan,” Pandya said, a label thrust on many Muslim-majority neighbourhoods across India.

In 2019, when news broke that a Muslim buyer acquired the Goradia bungalow, paranoia gripped the Hindu neighbours, according to Pandya.

Residential societies rallied together, launching signature campaigns to register protest, first with the municipal corporation and then with the district collector. But they were met with a fait accompli—the deal was done.

It was at this point that the provisions of Disturbed Areas Act came into the picture. The irate residents, with backing from local politicians, pooled in money and took their fight to court, claiming that the law’s provisions had been violated. Two policemen were even transferred after an internal probe indicated that the procedures for granting permissions were not handled properly.

A new law needs to be brought in so that everybody can live everywhere and there is protection to do that

-Narendra Rawat, Congress leader

Pandya objects to the deal himself, but insists this is because it’s a symptom of systemic inequality where the wealthy can easily “breach” the government system.

In the neighbourhood, anxieties had reached a fever pitch and it was all anyone could talk about. “They thought it was going to be unsafe now, the entire society will be broken down, the entire area will be taken over by Muslims,” Pandya said.

According to both Pandya and the Vadodara-based Hindu builder, these fears were not entirely unfounded. Both claimed that after the “Angan bungalow”, a residential society in the same neighbourhood, the entire colony underwent a demographic change. However, neither was able to provide a clear timeline of when this transaction happened.

While Pandya readily conceded that ghettoisation was not the way forward for Gujarat’s development, he also pointed to the impracticality of integration in this deeply segregated area.

“Assimilation in the area is not possible because it has already been ghettoised. It has reached a level that a Hindu would be really sceptical in buying a business or residential property here,” he said. Some property listings, he pointed out, explicitly included “Muslims only” caveats.

Once a new Muslim buyer settles in, a nefarious pattern unfolds, according to the Vadodara BJP president. They allegedly deliberately create disturbances “with an intention” to drive other residents away, forcing them to sell their prime properties at bargain prices.

A plan to ‘protect’ Hindus

In October 2023, the Gujarat government announced its intention to revise the controversial amendments to the Disturbed Areas Act in the high court. Although the government did not elaborate further, Vadodara BJP president Shah hinted that the upcoming changes could be even more stringent.

At his Vadodara office, decorated with a miniature Ram temple at the entrance, Shah told ThePrint that the planned amendments aimed to close loopholes enabling property deals between communities. This, he claimed, would solidify the legislation’s original purpose of fostering social harmony—through segregation.

“The overall purpose is that everyone should live with harmony,” the BJP leader said. “Everyone goes back home for comfort. Until and unless you go through the situation, you can probably never understand how difficult it is to live with a community you are not comfortable with. And it’s not specifically about religion, it could be anything.”

Shah claimed that changes to the demographics of well-established neighbourhoods had to be resisted, hinting at wealthy Muslims purchasing properties at exorbitant rates.

“What is the process? One community lives in a specific area peacefully. Then the other community buys one small place there at a rate that nobody can afford. Because one person who believes that money is more important than the comfort of other people sells that property,” he began.

According to Shah, once the new buyer settles in, a nefarious pattern unfolds. They allegedly deliberately create disturbances “with an intention” to drive other residents away in distress, forcing them to sell their prime properties at bargain prices.

“The way they live, the way their culture is, the way they want people to get disturbed, the other people also start leaving the place. They are forced to leave at a price that is very low. That is how this segregation started, not in residential areas but in commercial areas also,” he said.

Any real estate developer promises his customers that he won’t give houses to a Muslim. With that assurance, he will sell these places at a premium price. The market has absorbed this mechanism. It’s serving the demand for purity

-Fahad Zuberi, graduate scholar

But Congress leader Narendra Rawat—who was to contest against Narendra Modi in 2014 from Vodadora before withdrawing his candidature—said that a law that was brought in to protect people’s rights was now being used for the opposite purpose.

“Since the BJP came into power, they’ve wanted to distance Muslims from Hindu areas. The Disturbed Areas Act has become a big weapon for them. They don’t care about society or the social fabric. The fabric is already broken,” he said. Now, if a Hindu wants to sell a property to Muslim, BJP organisations come together and file applications and raise protests, Rawat added, leaving both the seller and buyer stranded.

“A new law needs to be brought in so that everybody can live everywhere and there is protection to do that,” Rawat said.

Also Read: ‘Muslim kids at RSS shakhas, Hindus played at mosque’—Gyanvapi now a saga of who prayed where

The price of ‘purity’ in real estate

The Gujarat government hasn’t denotified a single area under the Disturbed Areas Act since its inception. Experts argue that the law has heightened communal divisions, making mixed neighbourhoods virtually nonexistent and fostering a class struggle that disproportionately impacts poorer Muslims, relegating them to the periphery. But even keeping aside this law, spatial boundaries between communities have become a way of life in Gujarat.

“There is a fundamental belief that Muslims and Hindus should stay separately. That’s how the illusion of peace is maintained in Gujarat. As long as you don’t change the status quo, everything will be safe and peaceful. Is this peace? This is rule by non-violence and law,” said Fahad Zuberi, a former architect turned academic and current graduate scholar in South Asian studies at Oxford University.

He contended that the Disturbed Areas Act legitimises “notional borders”, endorsing the idea of one community being “impure” and deserving of exclusion and discrimination.

These imagined boundaries extend beyond mental constructs and manifest in physical spaces, which often become flashpoints of conlict between communities. “There could be a road that marks the border. Police securitises it. You will find a lot of police stations in these areas,” he said.

Tandalja seems to exemplifies the concept of these imagined borders achieving tangible form—the lane where Patel has his cycle shop. At the end of this lane is the JP Road Police Station.

Zuberi emphasised that these boundaries stem from a “demand for purity”, achieved through exclusion.

“It’s the demand to live in a building that is not made impure by Muslims. So, any real estate developer promises his customers that he won’t give houses to a Muslim. With that assurance, he will sell these places at a premium price. The market has absorbed this mechanism. It’s serving the demand for purity,” he said.

I know it’s discrimination but we have been told we can’t make Muslim friends. So, I don’t have deep communication with them

-Vadodara student

The Disturbed Areas Act supports this idea of exclusion and purity. It’s a win-win for everyone with a power advantage.

“Real estate builders get to sell their property at a premium rate. People who want to live in ‘pure’ areas, get to do so, away from the dirty Muslims. The politics of discrimination and othering, the politics where the Muslim is seen as the dirty other, also continue to thrive,” Zuberi said.

At a bright café in Vasna-Bhayli Road, a few kilometres from Tandalja, three teenage girls played a game of UNO as they snacked on fruit salad and juice. They had just gotten off work as teaching interns at an English language centre. Two of them are using it as a springboard for university life abroad.

They are all from Gujarati Hindu families and none of them had even heard about the 2002 riots.

“It happened even before we were born,” one of them said.

But they were all aware of Tandalja being a Muslim neighbourhood. One of the girls said she had been warned by her family to stay away from the community. “I know it’s discrimination but we have been told we can’t make Muslim friends. So, I don’t have deep communication with them,” she said.

With sincerity, she clarified that while she harbours no personal bias, she doesn’t want to “disobey” her parents or the established “way of life”. However, she said she anticipated loosening these restrictions once she embarks on her undergraduate studies in the US.

“We have to maintain good relations with others when we are in a different country,” she said. “We have to build bonds where they will help us.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)