During economic expansion, the focus should be on improving the quality of employment, not just reducing the number unemployed people.

Some major Western economies are close to full employment, but only in comparison to their official unemployment rate. Relying on that benchmark alone is a mistake: Since the global financial crisis, underemployment has become the new unemployment.

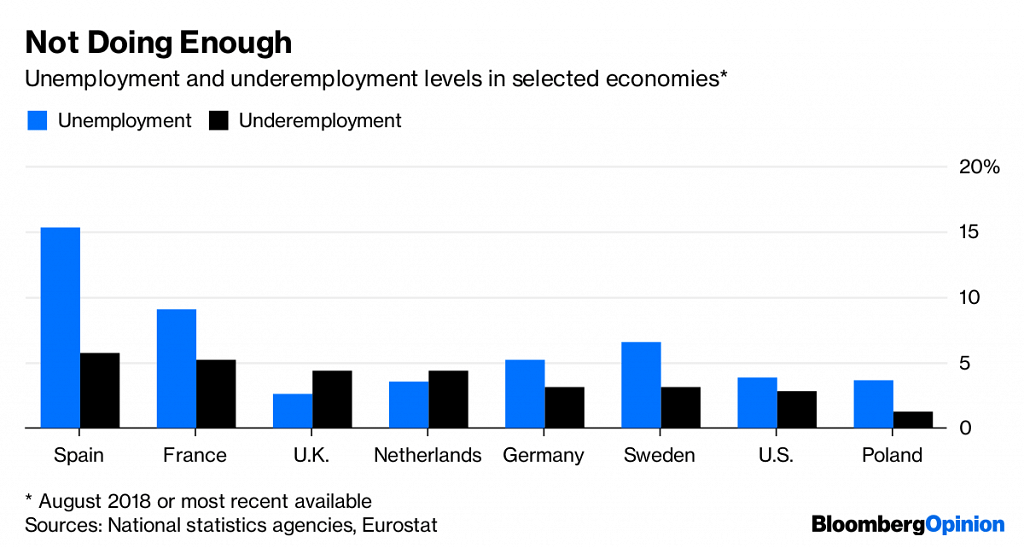

In a recent paper, David Bell and David Blanchflower singled out underemployment as a reason why wages in the U.S. and Europe are growing slower than they did before the global financial crisis, despite unemployment levels that are close to historic lows. In some economies with lax labor market regulation — the U.K. and the Netherlands, for example — more people are on precarious part-time contracts than out of work. That could allow politicians to use just the headline unemployment number without going into details about the quality of the jobs people manage to hold down.

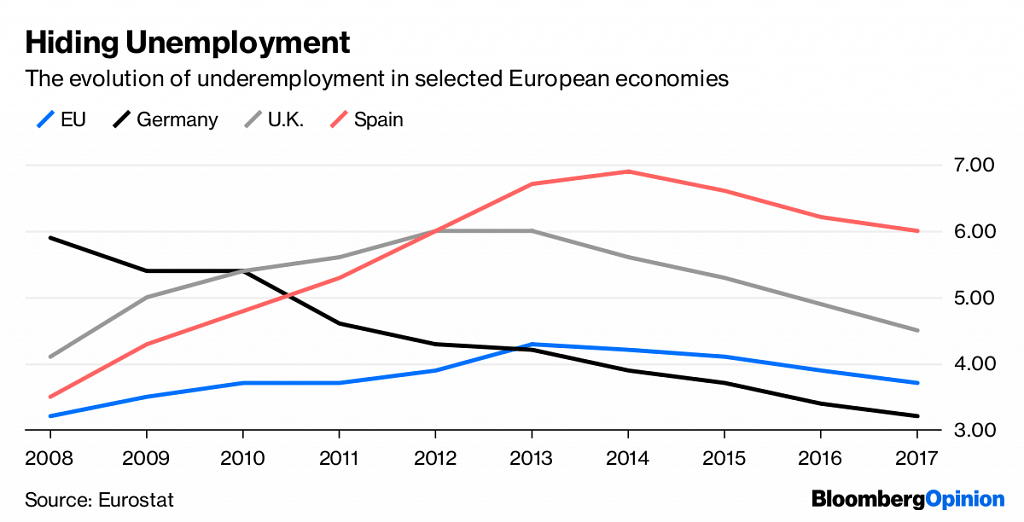

In recent months, leaders including President Donald Trump, U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May and German Chancellor Angela Merkel have bragged about record high employment. The veracity of these boasts varies, however. As different economies recovered from the global financial crisis, some relaxed labor regulations, creating more precarious jobs to drive down the headline jobless numbers and get more people off the dole. Spain, which had to deal with a joblessness explosion after the crisis, fought it by weakening worker protections and creating precarious jobs. It started out with an underemployment level of 3.5 per cent in 2008; that doubled by 2014, and has barely come down since. In the U.K., underemployment peaked in 2012 and 2013, and it’s still not back to the pre-crisis level. In the U.S., involuntary part-time employment rocketed in 2008 and 2009 and then started shrinking, but there, too, the pre-crisis level hasn’t been reached yet.

Germany is one of the few major economies that managed to drive down the number of people in precarious, part-time jobs in the post-crisis years. There, the sum of unemployment and underemployment is low enough for companies to start worrying about the lack of workers, at least at the wages they’ve been willing to pay. And indeed, German unit labor costs are rising faster than, say, in the U.K., where the pool of unhappy part-timers is bigger.

But even in Germany, both underemployment and unemployment statistics are rather fuzzy. Heinz-Josef Bontrup, an economist at the Westphalian University of Applied Sciences, argues that the official jobless rate means little because it doesn’t include, for example, people in government-sponsored training programs; as for underemployment, he says that about 13 million Germans who work an average of 15 hours a week, whether voluntarily or reluctantly, shouldn’t be counted as employed.

Measuring underemployment is difficult everywhere. To obtain more or less accurate data, those working part-time should probably be asked how many hours they’d like to put in, and those reporting a large number of hours they wish they could add should be recorded as underemployed. But most statistical agencies make do with the number of part-timers who say they’d like a full-time job. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t provide an official underemployment number, and existing semi-official measures, according to Bell and Blanchflower, could seriously underestimate the real situation.

The need for governments to show improvement on jobs since the global crisis has led to an absurd situation. Generous standards for measuring unemployment produce numbers that don’t agree with most people’s personal experience and the anecdotal evidence from friends and family. A lot of people are barely working, and wages are going up too slowly to fit a full employment picture. At the same time, underemployment, which, according to Bell and Blanchflower, has “replaced unemployment as the main indicator of labor market slack,” is rarely discussed and unreliably measured.

Governments should provide a clearer picture of how many people are not working as much as they’d like to — and of how many hours they’d like to add. Labor market flexibility is a nice tool in a crisis, but during an economic expansion, the focus should be on improving employment quality, not just reducing the number of people who draw an unemployment check. An increasing number of better jobs, and as a consequence wage growth, becomes the most important measure of policy success.