In 2002, the International Labour Organization (ILO) adopted 12 June as the annual World Day Against Child Labour, to highlight the number of children employed in work situations that are detrimental to their health, safety and education, and are against global norms and laws regarding the safety and well-being of children.

This year, the observance is aimed at examining how a crisis, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, will increase the number of children forced to work.

As countries around the world, including India face a recession and witness massive job losses and crippling of the informal sector, families will get more and more desperate to bring money home. In such situations, it is likely that the children of the household will be forced in to work as families would no longer be able to provide for them. Children, then, are at a greater risk of getting trapped in bonded labour.

Today, almost 1 in 10 children around the world are engaged in labour, and this is after a decline of 94 million since 2000. The UN’s sustainable development goal 2030 aims to eliminate child labour in all forms by 2025, but Covid-19 will stunt the progress towards this goal.

Loss of livelihood, reverse migration and shut schools

Unemployment, the closure of schools for extended periods and the return of many labourers to their villages will emerge as the biggest reason behind the anticipated increase in child labour in India, according to Kumar Nilendu, General Manager, Development support at Child Rights and You (CRY), an NGO. “For a lot of families in India, basic survival is threatened and in such a scenario, the child becomes the last priority,” he tells ThePrint. “In rural areas, children are much more vulnerable to getting trapped in labour, especially carrier and agricultural labour,” he adds.

There are about 10.11 million child labourers in India between the age of 5-14 years according to the 2011 census, and almost 80 per cent is concentrated in rural areas. Additionally, school closures have also affected more than 33 crore students, according to UNESCO in India, many of whom were dependent on mid-day meals being served in their school for at least one meal a day.

With reverse migration, children might get stuck in a cycle of trafficking, and the government would find it even more difficult to track them, according to Anshum Goswami, legal consultant in human trafficking and bonded/child labour.

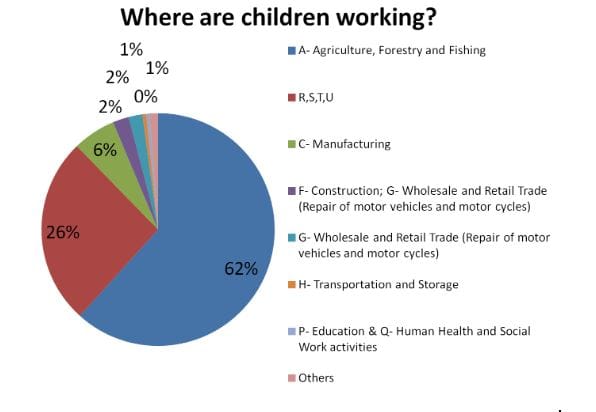

“Traffickers will try to get children working in industries in urban areas into bonded agricultural labour now,” Goswami says, explaining that “for a lot of such work, people want labour with ‘smaller hands’, which puts children below 14 at a greater risk.” Right now, the agricultural sector employs over 62 per cent of all child labour.

And right now, with an influx of people and their families at once due to the pandemic, district anganwadis and schools might not be able to handle the pressure. “We need to prepare to open more and more schools near villages in the near future,” Nilendu says, “we need to ramp up our digital infrastructure if remote schooling is the new reality, because only a few disadvantaged families have a smartphone.”

Policy overhaul

The first thing the government should do, according to Nilendu, is overhaul the Integrated Child Protection System (IPCS), which is on the back-burner of state budgets, and boost it with more funds to ensure immediate relief to vulnerable children.

“Every policy related to the welfare of women and children needs to be looked at,” he says, and “some serious thinking in accordance with budget allocation is required, formation of village child protection committees should be ensured, panchayats should be given more funds so they can prevent trafficking, labour officers should be responsible for one district so they can monitor the situation easily.”

The government’s One Nation One Ration Card scheme amid the pandemic to ensure vulnerable communities have access to food is one where Goswami sees an opportunity to document vulnerable children that will lead to a reduction in trafficking. “While enrolling the parents in the scheme, their children should also be well accounted for. The same children can then be identified and enrolled into the local government school. This way, the children will be fed and their families will have access to rations.”

Also read: Migrant crisis could’ve been averted if Modi’s One Nation One Ration Card scheme was ready