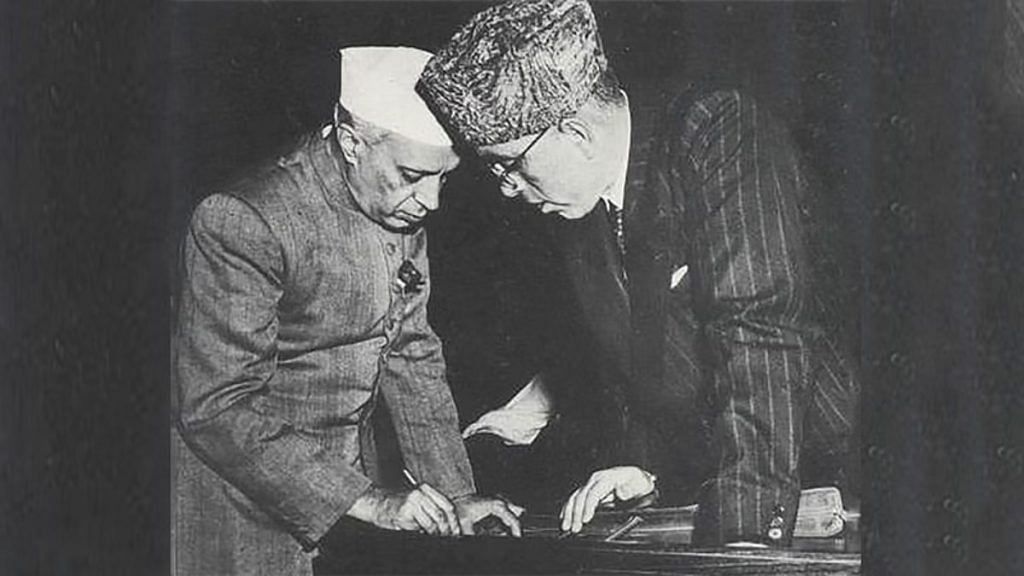

New Delhi: He is a saint to one generation and a traitor to another — but whether relevant today or not, Sheikh Abdullah’s shadow still looms large over the Kashmir Valley, forever entangled with Jawaharlal Nehru’s beleaguered legacy.

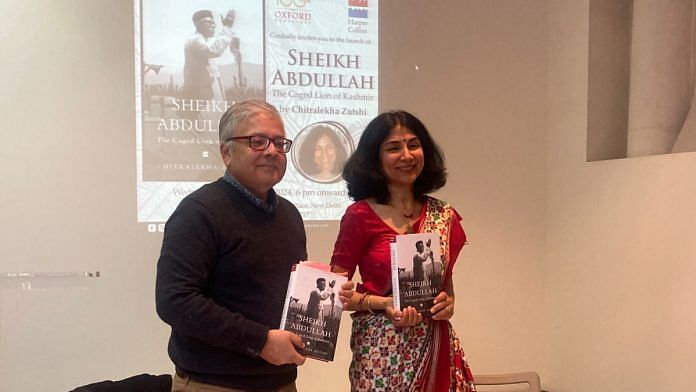

A new biography by historian Chitralekha Zutshi digs into the complexities of Sheikh Abdullah, one of the most controversial figures of the global 20th century. The book, Sheikh Abdullah: The Caged Lion of Kashmir, is the second in a series of biographies by HarperCollins curated by historian Ramachandra Guha.

One of the things that stood out to her while working on the book was how Sheikh Abdullah became the embodiment of the nation-building crisis in the late 1940s and 1950s — and how little power then-Prime Minister Nehru actually had over the situation.

Abdullah always felt that Nehru could have done more to quell the Praja Parishad movement in Jammu and Kashmir in 1952-1953, according to Zutshi. Nehru was writing daily to Abdullah to convince him to come to India, while Abdullah felt that Nehru didn’t try hard enough to help him.

If Abdullah had not been dismissed in 1953, he would have delivered a speech on Eid that year expressly saying that Nehru had not done enough to stop the movement in Kashmir. But it was never to be. History had other plans for both Abdullah and Nehru.

On a freezing winter’s evening, a group of twenty packed themselves into a cosy nook at the famous Oxford Bookstore in Connaught Place to discuss these themes at the book’s launch. The discussion on Abdullah’s life and his place in India’s political memory was set to the background noise of chatter at Cha Bar, the bookstore’s coffee shop.

Abdullah’s own personal conflicts came up several times: the discussion dissected his disappointments, his dreams, and his disastrous decisions.

“Much like Kashmir itself, his legacy is contested,” said Zutshi, adding that he was truly a 20th century international political figure, who was involved in global movements on anti-colonialism, federalism, and Islamic globalism. “This is not just a biography of Abdullah, but a biography of the entire generation of political leaders in the region.”

Also read: Lion of Kashmir, Sheikh Abdullah’s nationalism clashed with Nehru’s Indian nationalism

A ‘Kashmiri Muslim,’ not Indian

Sheikh Abdullah called Pakistan ‘Dakistan’ — dak being the Kashmiri word for ruin. He knew that the Partition of India meant that the Valley would now be caught between the two countries.

The Partition turned Abdullah’s hair grey, according to Zutshi. He was in prison during this period — and came out to stare at the face of a completely new subcontinent.

The discussion meandered through the various phases of Abdullah’s life, as his own politics changed along with the birth of modern India. The reason the book is called “Caged Lion” is because Abdullah was metaphorically caged by the Kashmir Valley, according to the author. As much as Abdullah tried to widen his vision, he was constrained by the politics of the Valley — and could never live up to his full potential as a leader for Indian Muslims at large.

“He could never fulfil each identity — Muslim, nationalist, secular,” said Zutshi.

His own complex relationship with India took up much of the conversation. In fact, Abdullah refused to call himself an Indian after 1953. When he filled out his passport in 1965 to go on Hajj, he identified himself as a Kashmiri Muslim, not Indian. This caused concern among the Indian establishment, who summoned him back from his travels abroad.

Zutshi was in conversation with novelist and journalist Aditya Sinha, whose own knowledge of Kashmiri added a spirited touch to the discussion. Sinha, who has written a book on Kashmir during the Vajpayee years, pointed out how the former PM brought up Abdullah’s passport in Parliament — a sure sign of displeasure over his stated identity.

Also read: Nehru shared blame for Kashmir problem. So, he freed Sheikh Abdullah & invited him to Delhi

A straight line to the present

Zutshi has been working on Kashmir for the past three decades, but only started working on this biography in 2013. But what was a revelation to her was uncovering the workings of the nascent Indian state: by going through Abdullah’s correspondences, she could see how the Indian state was being assembled.

In the process, the twists and turns of his life revealed deeper connections to the politics of Kashmir itself. The discussion made several references to the current politics of Kashmir and the revocation of the special status for Jammu and Kashmir, which the biography also traces to the origin.

“If you read this book, it charts a clear path to Article 370,” said Zutshi. “The seeds of this were sown even before the Article came into existence.”

The discussion was rounded up by a question from a law student in Kashmir: why is nobody talking about Sheikh Abdullah in Kashmir today? What’s responsible for dismantling his legacy? To the younger generations, he is very much eschewed as the reason for Kashmir’s current situation, answered Zutshi.

“Sheikh Abdullah is very much a persona non grata in Kashmir today,” she said. “His image has taken a severe knock.”

An hour after a huddled discussion at the back of a bookshop, many in the audience agreed that perhaps this new biography could help restore some shine to Sheikh Abdullah’s embattled legacy.

(Edited by Prashant)