New Delhi: As winter waned in north India in March, the best air quality index out of 257 cities was recorded in Varanasi. According to data analysed by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), the city had a PM2.5 concentration of 12, surpassing even the northeastern cities of Silchar in Assam and Shillong in Meghalaya, which have historically had good AQIs.

A study by New Delhi-based environment consulting firm Climate Trends earlier this month also found that in the winter of 2022 and 2023, Varanasi was the only one out of seven major cities that met the national air quality standards for PM2.5. levels.

All these reports seem to point to the same trend — Varanasi, a city on the banks of the river Ganga which, until 2019, had just one air quality monitoring system, and had an AQI as high as 388, has seen a steady improvement of air pollution and is now touted to be one of the best, not just in the Indo-Gangetic Plain (IGP) but also in the country.

On its part, the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board — the state’s air pollution regulator, puts it down to an action plan that has paid off well. Sanjeev Kumar Singh, member secretary of the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board, told ThePrint that under the National Clean Air Programme, the board devised a plan to tackle air pollution in Varanasi.

“We cleaned the pavements and undertook tree planting activities, and the presence of the Ganga too acts as a sink and reduces air pollution,” he said.

ThePrint’s analysis of real-time and manual air-quality data, however, points to some gaps. According to experts, this, along with factors such as fewer air-quality monitoring systems, could be affecting the quality of the findings.

“The surprisingly low values of PM2.5 in Varanasi compared to other similar geographies in IGP raises questions about the data quality for the city, primarily indicating that either the positioning of the monitors isn’t capturing the representative ambient air quality of the city or the monitors aren’t working properly and are underestimating the air pollution levels in the city,” said Sunil Dahiya, a senior analyst at CREA — a Finland-based independent air pollution research organisation whose March report too pointed to a downward trend in Varanasi’s air pollution.

Also Read: This is how London tackled air pollution. Delhi can learn

History of Varanasi’s air quality

There are four real-time air quality monitoring stations across the 162 sq. km expanse of the city — Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s parliamentary constituency — including one inside the lush green Banaras Hindu University (BHU) campus.

A second station is located in the city’s Ardali Bazar and surrounded by buildings on three sides. This is despite the Central Pollution Control Board of India (CPCB)’s guidelines explicitly stating that large structures should not obstruct air quality monitors.

CPCB does real-time air quality monitoring. Given that this data is voluminous, most organisations including Climate Trends and CREA use this data to calculate AQIs.

On the other hand, manual data is updated by the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board every month on their website. CPCB’s protocol requires a minimum monitoring of twice a week or 104 days a year for manual monitoring.

In 2017, Varanasi made headlines for its poor air quality, which some news outlets said was “worse than Delhi”. An analysis of the CPCB’s data by IndiaSpend that year showed that Varanasi’s AQI was higher than Delhi’s and 20 times above what the World Health Organization (WHO) considers safe.

Even this information was gathered from manual monitoring stations that only recorded data for pollutants such PM10 particles, sulfur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and not PM2.5 particulate matter, which are smaller and cause more harm.

Stubble burning in the IGP, vehicular emissions, construction, and road dust are some of the main causes of air pollution in the region. Significantly, PM2.5 particulate matter is emitted by all of them.

According to Ravi Shekhar, a Varanasi-based environment activist working for clean air in Uttar Pradesh through his NGO Climate Agenda, air quality improvement happens with changes in the infrastructure, transport, and tree cover, and when all sources of pollution are addressed.

“In Varanasi, we’ve actually seen more traffic jams, more construction, and worse waste management than a few years ago. But the AQI is contradictory to what we see on the ground,” he said.

Data also indicates significant construction activity in Varanasi. According to the website for Members of Parliament Local Area Development Scheme — the scheme enabling MPs to recommend development work in their constituencies — of the 399 projects Modi recommended for his constituency in just the last six months, 43 percent were construction-related.

In its report, the New Delhi-based Climate Trends looked at CPCB’s winter pollution data for seven cities — Mumbai, Varanasi, Patna, Delhi, Chandigarh, Lucknow, and Kolkata — and found that only Varanasi managed to meet India’s National Ambient Air Quality Standards of 60 µg/m³ (micrograms per cubic meter) in 2022-23 and 2023-24.

Even the highest PM2.5 concentration level recorded in Varanasi (121 µg/m³) was three times lower than Delhi’s highest level (405 µg/m³), the report showed.

The organisation’s January analysis of data from the National Clean Air Programme for the last five years showed that out of 132 cities, Varanasi had the highest decrease in its PM10 and PM2.5 levels and was in the list of least polluted cities — alongside cities such as Silchar in Assam, Rishikesh in Uttarakhand and Srinagar in Jammu and Kashmir.

Even within the Indo-Gangetic Plain, considered one of the most polluted stretches in the country in the last few years, Varanasi was the only city in January 2024 that was the ‘green’ zone with good air quality — every other city, from Delhi to Patna, Lucknow, and Kanpur, ranged between very poor to moderate.

Shekhar pointed out that air quality isn’t restricted to administrative boundaries. He also found it odd that, of the IGP cities, only Varanasi could have good air quality.

Newspaper reports from 2023 also show that while some parts of the city recorded AQIs as high as 400, the CPCB’s classification based on real-time monitoring stations still placed Varanasi in the ‘green’ zone.

“The air quality in Varanasi has not improved as drastically as the data shows. I don’t know what the issue is but the air quality monitors aren’t completely and accurately capturing the data in the city, because the ground reality is very different from what these monitoring stations show it to be,” he said.

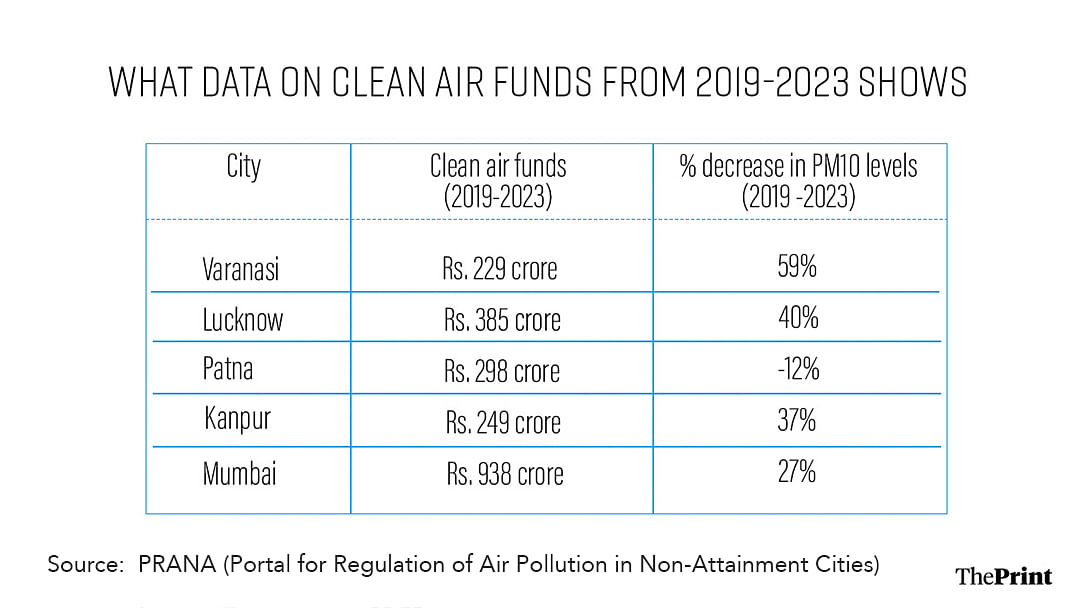

The information about clean air management funds also doesn’t reveal much. According to the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s Prana portal, Varanasi has received Rs 229 crore in funds from the National Clean Air Programme and the 15th Finance Commission from 2019 to 2023. During this time, its PM10 levels decreased by 59 percent.

Patna in Bihar, which received Rs 298 crore during the same period, saw an increase of 12 percent in its PM10 levels. Within UP, Varanasi saw the largest decrease in air pollution, the data shows.

While Lucknow, which received Rs 385 crore, saw PM10 levels drop by 40 percent, Kanpur, which got Rs 249 crore, saw a decline of 37 percent.

Varanasi appears to have done better than even metropolitan cities like Mumbai, which, despite having received Rs 938 crore for air quality management, saw only a 27 percent drop in PM10 levels.

Fewer monitoring systems, data quality issues

The Varanasi air pollution action plan, necessary for all non-attainment cities under the National Clean Air Programme 2019, is almost identical to the action plans of other UP cities such as Noida and Ghaziabad, which continue to be plagued by poor air quality.

Under the programme, using electric buses, cleaning dust off roads, and using smog guns are standard air pollution measures.

While Varanasi saw a 72 percent decrease in its AQI from 2019 to 2023, other cities in the IGP featured in 18 of the top 20 most polluted cities, according to a Climate Trends report.

However, data on the Prana portal shows that, unlike other IGP cities such as Delhi, Patna, Kanpur, and Ghaziabad, Varanasi has not even completed its source-apportionment study — mandatory under the 2019 National Clean Air Programme to determine what are the sources of pollution in a city.

The Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change launched the scheme in 2019. According to the portal, Varanasi is among the 87 cities that have yet to complete the source-apportionment study.

Of the seven cities analysed in the Climate Trends report, Varanasi — along with Chandigarh — has the lowest number of air quality monitors. By contrast, cities such as Patna, Kolkata, and Lucknow have 7-8 stations, while Delhi has 40 — the most in any city in India.

According to Dahiya, fewer air quality monitors could mean data quality was affected.

“The cities with fewer air quality monitoring stations are more likely to be influenced by very local activities, i.e., high emitting pollution source/activities in the vicinity of the monitors, reduced exposure of the monitors to ambient air pollution by enhanced moisture in the vicinity of the monitors, etc.,” he explained, adding that the only way to mitigate such biases is to increase monitoring stations substantially and sharing transparent information with the public.

The data quality issues pointed out by Dahiya and Shekhar are echoed by other analysts like Palak Balyan of Climate Trends. Speaking to ThePrint about her March report on winter air quality in Indian cities, she pointed out the limitations of the study.

“More research is needed to understand this phenomenon better. But certain factors like the number of air quality monitoring stations in the city, and where they are located too could influence this data. Some cities like Delhi have over 40 monitoring stations, while some might only have 2-3,” she said.

Another issue in Varanasi is the disparity in the data from manual monitoring stations versus real-time stations. Varanasi currently has five manual and four real-time stations, with BHU being the only one that does both.

Manual and real-time monitoring stations use the same methodology to capture data about pollutant concentration per cubic metre of air. However, for manual stations, the analysis of air quality samples is done manually in a laboratory and then uploaded, while real-time monitoring stations have in-built analysis systems that doesn’t require manual intervention.

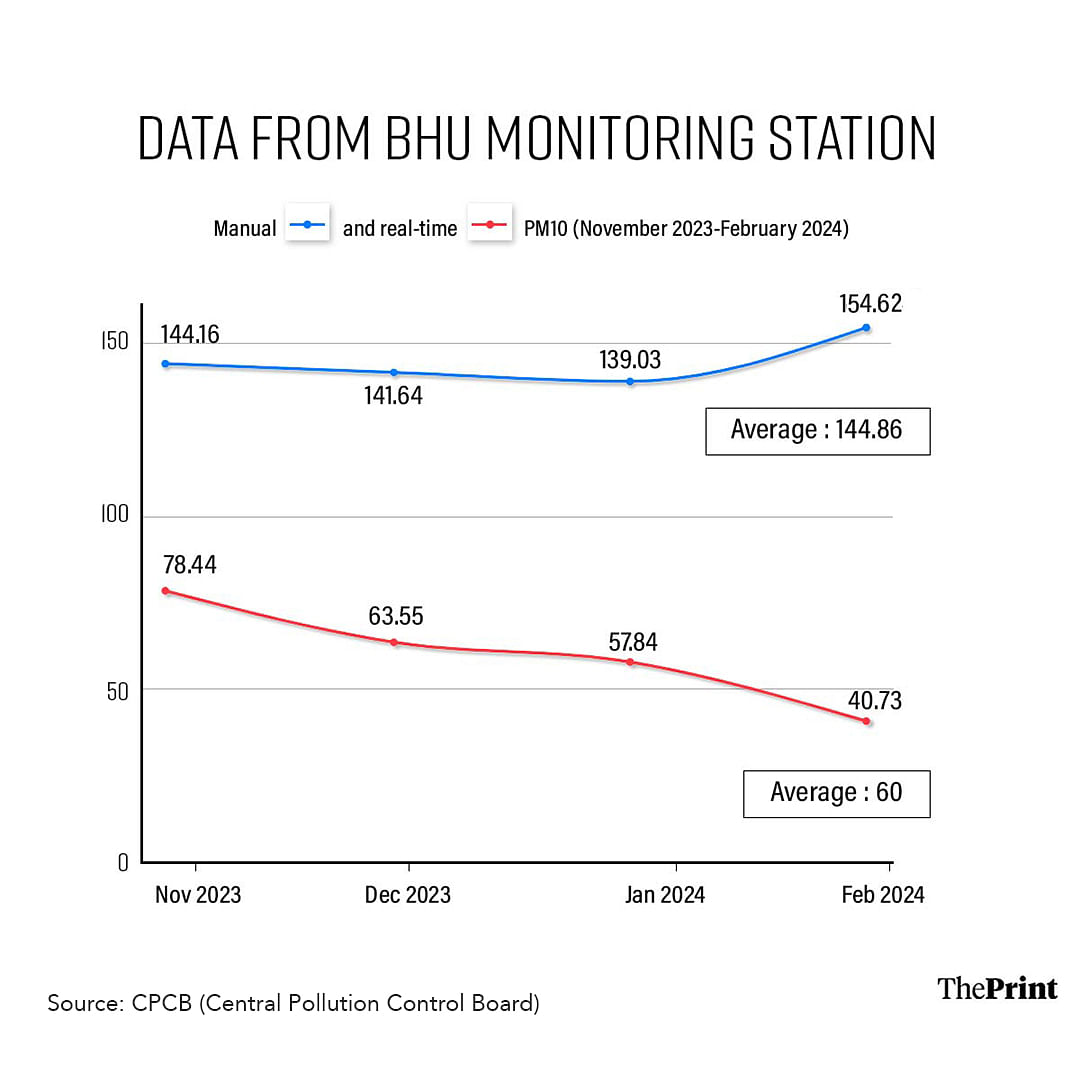

ThePrint analysed real-time and manual air quality data from Varanasi’s stations from November 2023 to March 2024 and found huge contrast in PM10 readings at BHU. The monthly average PM10 level for BHU’s real-time station ranged from 78.4 to 40.7, while the manual data was between 139 and 154.

The overall average for manual was 144.8 — more than twice the real-time reading of 60.

According to S.N.Tripathi, a professor at IIT Kanpur’s Sustainable Energy Department (SEE), this discrepancy is too wide to be usual.

“Usually, we expect some discrepancy between manual and real-time data within the standard deviation, owing to the different ways in which data is collected. Manual is a monthly figure while real-time is collected every 15 minutes. But such large discrepancies where one data is double the figure of the other isn’t normal and shouldn’t arise,” Tripathi told ThePrint.

Climate Trends, CREA, and most other air pollution analysts use real-time data because it is readily available on the website. Meanwhile, manual data needs to be updated every month and leads to delays.

However, Dahiya says there’s a need to develop a holistic air quality index that takes into account the average of both readings.

When asked about the variation in the data, Sanjeev Kumar Singh of the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board attributed it to the difference in manual and real-time data collection.

“Manual stations only record data for 104 days a year, while real-time stations record it every day. I agree such huge differences are rare, but the real-time stations are what the CPCB uses and we rely on it too,” he said.

He also categorically denied any data quality or monitoring problems in Varanasi, saying that the air pollution board uses “state-of-the-art equipment that meets international standards to measure air quality”.

“You can say that there are fewer monitoring stations, I agree. But you cannot raise allegations against the data,” he said.

The solutions

Dahiya, Tripathi, and Balyan all acknowledge the need for more monitoring stations to get a more accurate sense of the data for an area as large as Varanasi.

“To better understand the air quality and the exposure of citizens to bad air, we need more monitors and a hybrid monitoring system with real-time monitoring and sensors in appropriate locations,” Tripathi said.

Despite his denials on data quality, UPPCB official Singh acknowledged the need for more air quality monitoring stations. But he also said that real-time monitoring systems are expensive.

“We are switching to real-time monitoring because it provides accurate information readily, but one device costs upwards of Rs 1 crore,” he explained, adding that the WHO is currently working with states in the Indo-Gangetic Plain to ramp up air quality monitoring and that there are plans to set up 190 more stations over the next few years.

Shekhar, meanwhile, points out the perils of publishing reports extolling Varanais’s improving air quality. When such reports are published, people stop caring about how their actions affect the air, he said.

“Only looking at data from a distance won’t give you information on the ground. However, it will undo the work done by activists over the years to make people aware of air pollution’s harmful effects. When people see these headlines, they’ll think the air has improved and their job is done, but that it isn’t true,” he said.

This is an updated version of the story.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: India’s National Clean Air Programme hasn’t curbed pollution. It needs Swachh Bharat-like push