Firozabad: In Firozabad’s Imam Bara bangle mandi (market) — some 200 km from the national capital Delhi — 54-year-old Ghulam Mohammad is waiting for customers. Around him are shimmering glass bangles of varied colours — from traditional red and green to an eye-watering orange.

It’s wedding season but this dusty and languid part of Firozabad — home to a major glass bangle industry — bears no signs of any frenzy. As the sun casts its long afternoon shadows, bangle traders like Ghulam Mohammad sit inside their shops in the near-empty street, whiling away the hours until closing.

“There was a time when the area from Imam Bara to Rasulpura used to be bustling with buyers. It was difficult to pass through here,” Mohammad tells ThePrint. “But now it remains mostly empty. That should tell you enough about the state of the (glass bangle-making) industry.”

Known as ‘kaanch nagari’ (glass city) and ‘suhag nagar’, this small industrial town in western Uttar Pradesh is facing a major challenge — its 200-year-old glass bangle industry, once its pride, now appears to be on its last legs.

Of its 120 bangle-making units, only 50 are currently functional. The rest are either closed for maintenance or shut down completely, with some even being converted into the more lucrative bottle-making business.

So what ails Firozabad’s famed bangle industry? According to economists, factory owners, and industry experts ThePrint spoke to, it’s a compounding of factors, from changing fashion trends and declining demand for glass bangles to disruptive government policies such as the 2016 demonetisation and the rising price of natural gas — essential for the industry — that have led to this situation.

The industry’s problems are aggravated by the fact that the city comes under the Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ) — a defined area of 10,400 sq km around the Taj Mahal to protect the monument from pollution.

“Business is not going well,” 55-year-old Jamil Khan, the manager at the Saubhagya Glass Industries near Imam Bara Bangle Mandi, tells ThePrint. The factory has been making glass bangles for 50 years but is now working at only half its capacity — another sign of a flagging industry.

The situation has worsened in the last 2-3 years, Khan says. “This year there is no demand at all. And no government has done anything for us.”

With Firozabad going to polls on 7 May, problems related to its mostly unorganised glass industry — which includes its bangle-making sector — are taking centre stage. For instance, Thakur Vishwadeep Singh, a glass industrialist and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) candidate for the constituency, has promised a separate manifesto for Firozabad’s glass industry.

“I have been dealing with these problems every day and am well aware of them. If I win, I will fix them,” Vishwadeep Singh tells ThePrint.

However, economists say that’s easier said than done — factors such as increased automation mean that Firozabad’s labour-heavy glass industry can’t compete with other glass-making markets. This means Firozabad has lost its monopoly over the industry, says Prashant Agarwal, a professor of economics at the city’s SRK College.

“Firozabad has always been a labour-heavy market, but with changing times and due to mechanisation, labour is no longer a big issue. That’s why glass industries are shifting to other areas,” the professor, who published a research paper titled ‘Health and Environmental Impacts of Glass Industry: A case study of Firozabad Glass Industry’ in 2014, said, adding that rising ancillary costs, such as that of natural gas, are now affecting the industry.

On his part, a senior official from the Firozabad administration admits that only policy intervention can help the bangle industry survive. But he also says that while the district administration can only render limited help to the industry because the area comes under the TTZ, it is “working” to help the industry. “We take the problems of industrialists seriously and work on them,” this official said.

Also Read: How Akhilesh Yadav’s daughter Aditi is learning ropes on campaign trail in family bastion Mainpuri

Declining demand

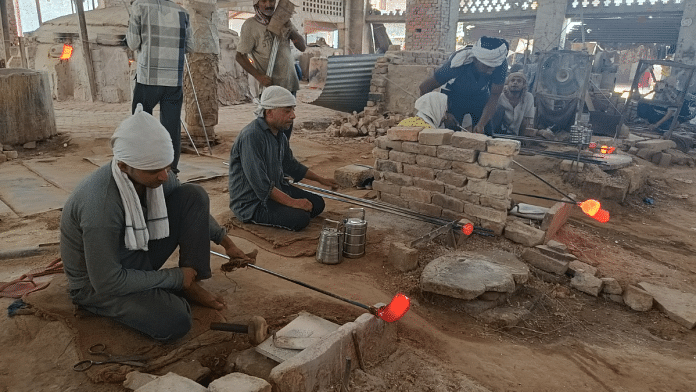

Bangle-making, like glass-making in general, is challenging work. A mixture of sand, soda, and chemicals is fed into an earthen furnace and melted at 1,200 degrees Celsius. This creates a gob of molten glass, which is then scooped out and beaten into a cone to help carve out bangles. This is eventually passed through a machine to help sift out the damaged pieces.

The process is time-consuming, taking up to 12-15 hours to just melt the glass. Since this is done at very high temperatures, the areas around the furnaces — or bhattis — get extremely hot.

At Saubhagya, 200-odd employees are hard at work. A gulliwala scoops a gob of glass out of a furnace and carries it to the karigars (artisans), who will mold this lump into colourful bangles.

In one corner, Khan opens his record book for inspection. This factory, which used to function for 24 hours until five years ago, now does only 12. “Many big factories in Firozabad were closed or converted to bottle-making units. For many owners, running factories became a loss-making deal,” he says morosely.

According to the 2019-2020 study on Firozabad’s glass bangle industry by Pune’s Flame University, the Modi government’s 2016 demonetisation crippled heavily cash-reliant glass bangle industry.

“All stakeholders were hence left without cash for transactions or bulk orders. The introduction of GST (the Goods and Services Tax) created more problems for the industry by creating tax rule divides between the retailers and the wholesalers,” the study, titled ‘Chudiyan: A study into the lives of Firozabad’s glass bangle industry workers’, says.

Another contributor was the increasing demand for bangles made of brass, metal, and seep. Mohammad Alkaab, who works at the Saubhagya factory, says: “Bangles have always had great importance in Indian tradition. It has been associated with weddings, which is why this industry is still alive. But times have changed and the interest in glass bangles has declined.”

Significantly, while there’s a fall in the demand for glass bangles, there’s more demand for brass and metal ones from Rajasthan and Delhi. As a result, traders too have begun to stock more of those.

“More than half of the bangles we sell are from Rajasthan,” says Imran Shagir, who owns a bangle shop in Firozabad’s Naya Rasoolpur. “What can be worse for this industry?”

How bangle factories were affected

According to a 2019 Union Ministry of Small and Medium Enterprises report, the glass industry is a major source of income — either directly or indirectly — for over 50 percent of Firozabad’s population.

The city also accounts for 70 percent of India’s total unorganised glass production, with nearly 35 percent of its products exported to other countries, the report, ‘Cluster Diagnostic Report and Action Plan Glass Cluster, Firozabad’, says.

The glass industry is divided into three large sub-groups — bangle-making, glassblowing, and bottle-making.

According to various businessmen ThePrint spoke to, Firozabad’s glass industry is estimated to have an annual turnover of Rs 10,000 crore, with a total capacity of 5,000-6,000 tonnes per day. Of this, bangle-making is estimated to be a Rs 1,000 crore industry, with a production capacity of 1,500 tonnes per day.

Until 1996, most of the bangle-making units used coal for production. But that year, the Supreme Court, concerned about the effect of pollution on the Taj Mahal, passed an order not only prohibiting any increase in manufacturing units, but also asking the existing industry to shift to natural gas.

According to the city’s businessmen, this order had a lasting effect on the glass industry. Until then, there were 600 small and big industries in the entire area of Agra and Firozabad. While 400 of these moved to natural gas, the others were forced to shut down or relocate.

Among those who faced the consequences of compounding industry problems was Nitin Goel, in his 40s. Goel had to close down his bangle factory after the COVID-19 pandemic because he could not afford the rising cost of natural gas.

For context, according to a notification from the Union petroleum ministry on 30 April, the rate for domestic natural gas for the period between 1 May and 31 May is notified at US$ 650.90 /MMBTU (Rs 541.97).

Today, Goel owns a wholesale bangle shop at the bangle market. “Many like us couldn’t afford to keep running the factory,” he says, adding that many bangle-making units are now of the city’s bustling market.

According to Sanjay Aggarwal, president of the All India Glass Manufacturers Federation (AIGMF), while the central government began to provide natural gas to the local glass industries to help them survive after the SC order, many bangle-making units couldn’t benefit from it, and remained at a disadvantage.

“This industry was not in a position to expand itself because it was not an organised sector but was scattered across Firozabad.”

In 2012, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government changed its pricing policy by introducing a Unified Price Mechanism (UPM) for all similarly situated industries.

For the glass-bangle industry, this pricing change meant that natural gas became even dearer. “The bangle industry was greatly affected by the increase in gas prices and could not absorb it. From 2015, many converted to bottle-making units, which isn’t traditional here,” AIGF president Aggarwal says.

In his speech in Firozabad on 2 May, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath claimed that his government’s policies have taken the region’s industry to greater heights. “Today Firozabad is known in the world for its glass work,” he said.

But factory owners want more. “The industrialists here are not in a position to fight for their rights because there are many restrictions that prevent them from expanding their businesses,” Sanjay Aggarwal, who also owns Kwality Glass Works, tells ThePrint.

Mohammad Saif, manager at Nadar Bux & Co Glassworks — one of Firozabad’s oldest bangle factories — agrees. “Work is not like it used to be. Running a factory is no longer an easy task. Raw materials are becoming expensive. Operational costs have increased manifold but there’s no corresponding demand in the market.”

Like economist Prashant Agarwal, Firozabad Vyapar Mandal President V.S.Gupta, too, blames the lack of innovation for the state of the bangle industry.

“This has always remained an unorganised sector. Although the laborers here are quite skilled and know their job well, they continue to work in the traditional manner. No innovations were introduced,” Gupta, who’s also in the bangle business, tells ThePrint.

Rise of bottle-making industry

Although there is no official data, various unofficial estimates say Firozabad has a total of 198 glass-making units, including bangle-making units. Of this number, 160 are functional.

A decline in the traditional glass bangle-making units has corresponded with an increase in bottle-making units — according to AIGMF president Sanjay Aggarwal, the number of bottle-making units has gone up from 1-2 in 1996 to 22 currently. Alcohol bottles make up 80 percent of the total bottle production, he adds.

So what accounts for this shift towards the bottling industry? According to economist prof. Prashant Agarwal, it was due to the factors cited earlier, along with technological advancements such as the invention of the LED bulb. This led to a decline in the glass bulbs produced in Firozabad.

“In such a situation, the industries here had no other option but to shift towards the glass bottle industry. Today, Firozabad is making a large number of bottles which are in demand in the world. And work is being done in a mechanised manner instead of using manual labour,” the professor says.

All of this signals the slow end of the bangle-making industry. To help it survive, the economist calls for urgent policy intervention. “There should either be some systemic overhaul or new policy initiatives to help the bangle-making industry survive. Otherwise, it’s taking its last breaths.”

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)