New Delhi: Frequent disinvestment of government stake, muted production levels, high dividend payouts to the government and coal pricing have hurt Coal India — the largest coal-producing company in the world — leading to a steady erosion of its market capitalisation since 2015.

Coal India has also faced investor concerns over a possible fall in demand for the fossil fuel amid a strengthening push for renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power, and the uncertainty brewed for a year, in 2017-18, by the appointment of a slew of temporary chairpersons didn’t help matters either.

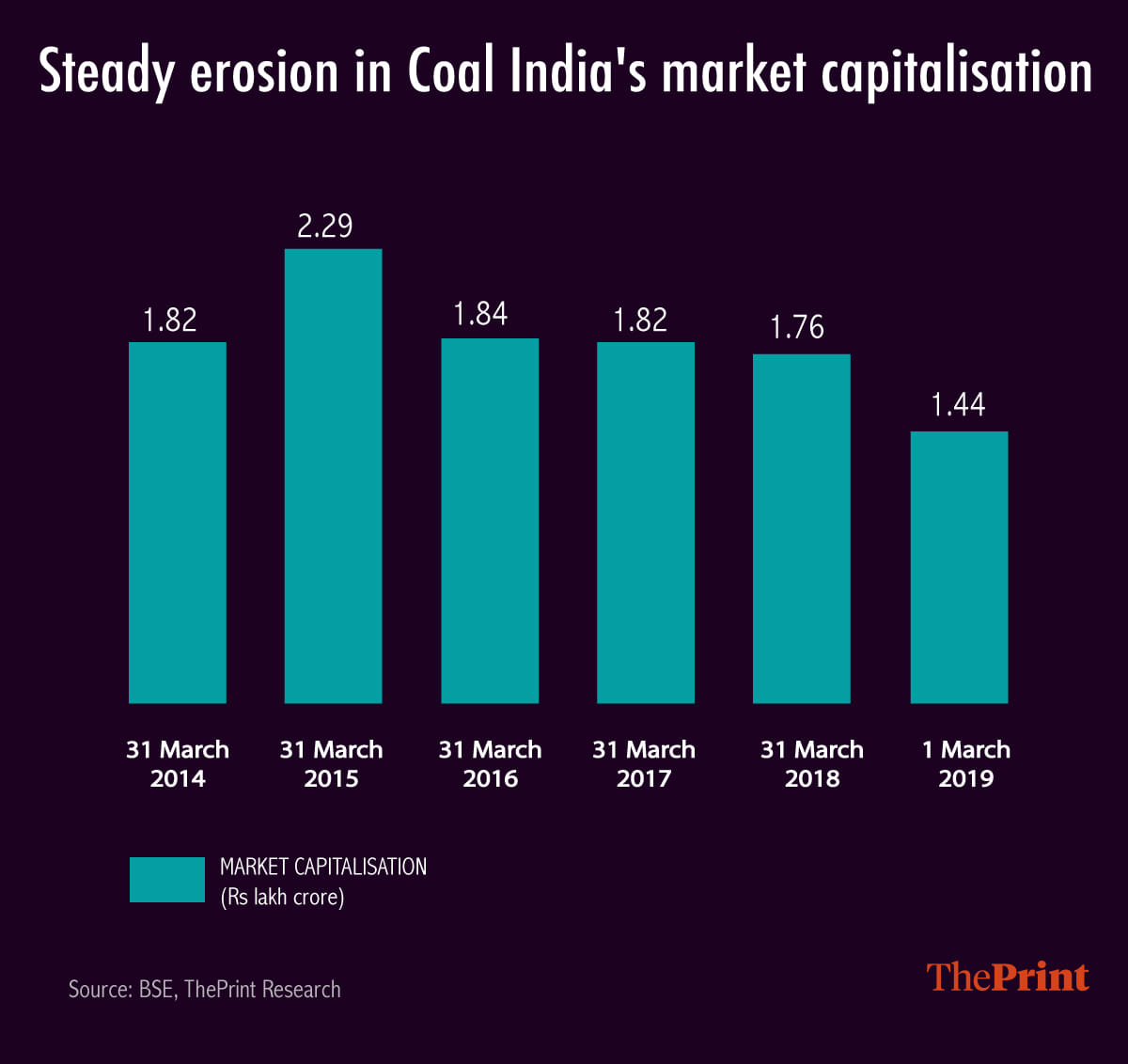

During the tenure of the Narendra Modi government, Coal India’s market capitalisation peaked at Rs 2.29 lakh crore in March 2015. It has fallen ever since, with the market cap standing at Rs 1.44 lakh crore as of 1 March 2019, according to data from the stock exchanges.

Meanwhile, the share price of Coal India — a Maharatna company — fell approximately 36 per cent to Rs 232.45 (1 March 2019) from Rs 362.4 on 31 March 2015.

Analysts and sector experts attribute the erosion of market capital to a host of reasons.

Ashutosh Tiwari, head of research-institutional equities at the investment bank Equirus Capital Private Ltd, said Coal India’s share price had come down on account of the constant talk about the promoter, the government, divesting some stake.

As of December 2018, the government held a 72.9 per cent stake in Coal India, down from 78.3 per cent in September 2018, and nearly 90 per cent in March 2014. Since 2014-15, the government has sold more than Rs 33,000 crore of Coal India’s shares.

“There is always some news of the government divesting some stake to meet its divestment targets,” Tiwari added. “This reduces the prices as the issue is typically offered at a discount to the market price [to attract investors].

“In addition, the volume growth of sales and production has always been muted,” he said.

However, Tiwari added that the performance of Coal India had improved in 2018-19 as “improved” benchmark coal pricing offset the impact of wage increases on profitability.

The Coal India chairman did not respond to an email sent by ThePrint for his comments. The coal giant’s spokesperson too had not responded by the time of publishing. This report will be updated when a response is received.

Also read: The future of coal is dark

Many a reason

According to former Union coal secretary Anil Swarup, the “first and foremost” reason for the fall in Coal India’s market cap was “the absence of a full-time chairperson for nearly a year in 2017-18”.

“An organisation like Coal India cannot make do with a temporary chairperson,” he added.

“The second reason is the enhanced dividend payout, which came under government pressure and not on account of increase in profits. This adversely impacted the cash reserves of the company,” said Swarup.

“Another reason is the limit placed by the government on the amount of coal that can be auctioned. Auctioned coal fetches a better price any day compared to the coal allowed for linkages based on a notified price,” he said.

In a research note dated 20 February, the financial services firm Motilal Oswal had pointed out that the Coal India stock had seen a fall over the last two to three years despite having a strong return on equity (RoE).

The RoE is described as “a measure of financial performance calculated by dividing net income by shareholders’ equity”.

The research note had also pointed out concerns among investors about the sale of Coal India shares even in a weak capital market, and the potential impact on the demand for the fossil fuel amid the shift towards green energy sources over worries about climate change and pollution.

However, allaying the concerns of investors, the report said there was a large scope for import substitution — boosting local production to offset the need for imports — as domestic coal production still met only two-thirds of India’s demand.

“Coal India’s ability to ramp up production and evacuation are the only bottlenecks,” it said.

The report added that the government “can reduce its stake by another 20 per cent maximum else it can lose control, which would be worth Rs 22,000 crore at the current market cap. Future selling will be much less than in the last five years”.

Also read: Modi govt promised to end coal imports by 2016, but they’ve been on the rise since then

People are looking for shortsighted immediate gains -only encashed fossil fuel market -but show a blind eye on the long term gains accrued from saving fossils underneath.