This cycle is unlikely to start reversing till the new bankruptcy law grows up a little.

Imagine India’s GDP growth had collapsed to 3 per cent; inflation was about to hit double digits; exports were tanking; and the country’s twin deficits — in the government’s budget, and in the nation’s current account — were out of control.

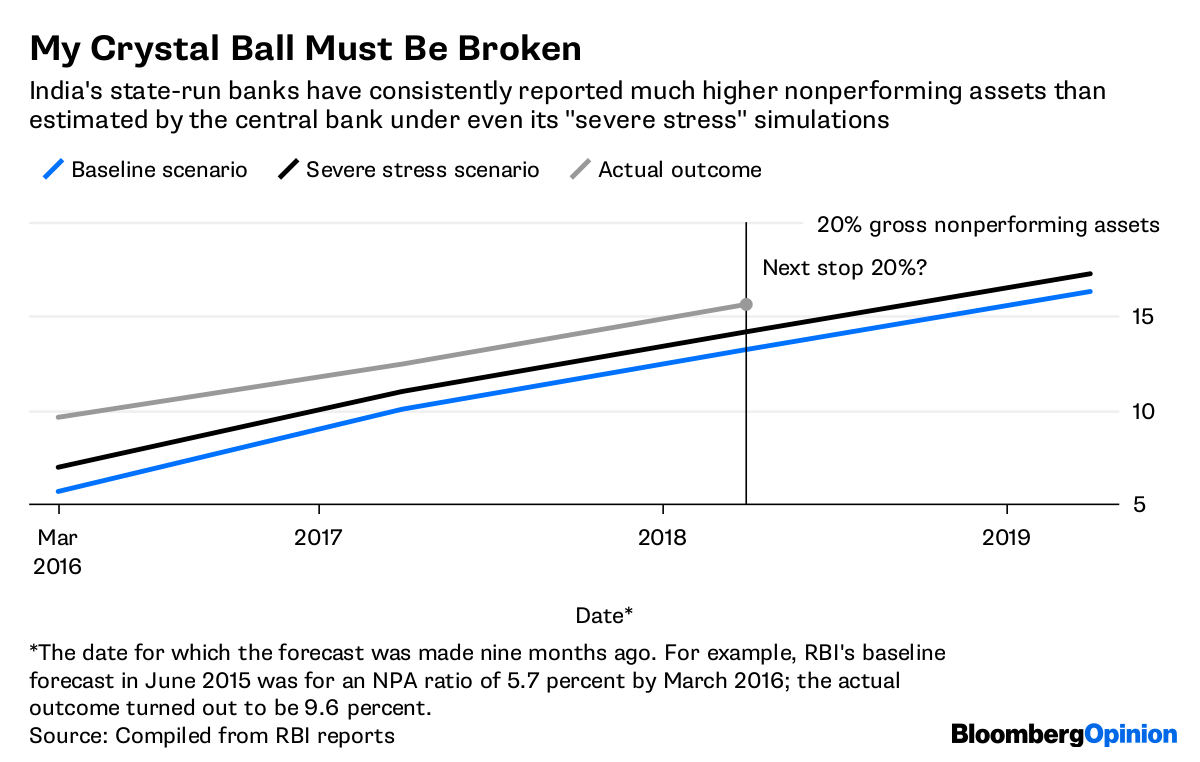

It’s only when the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) tries to imagine such a dire scenario for March 2019 that its simulation exercise for bad loans throws up a figure of 17.3 per cent of state-run banks’ total assets. Since most reasonable investors would dismiss the possibility of economic ruin lurking just around the corner, they’re likely to take comfort from the central bank’s baseline estimate of distress: 16.3 per cent.

While that’s still a scary number for a group of lenders that control 70 per cent of the banking system’s assets, it suggests the bulk of the pain is already in the rear-view mirror. With state-run financial institutions disclosing an aggregate nonperforming asset ratio of 15.6 per cent in March, a 0.7 percentage point increase projected over 12 months could even give rise to hopes of a recovery.

However, putting too much faith in the RBI’s stress test could end up misleading investors. The asset-quality problem is very likely heading for the 20 per cent mark.

Just look at the last three years of data.

In June 2015, 2016 and 2017, the baseline estimates of distress RBI gave in its stress tests were on average 3 percentage points lower than the actual NPAs of government-controlled lenders nine months later. In fact, the outcomes were around 2 percentage points worse than what the central bank saw when it asked its crystal ball about a “severe stress” scenario.

What if this year is no different?

To make an allowance for the RBI’s optimism, you should add 3 percentage points to its baseline Non-Performing Asset (NPA) projection of 16.3 per cent. In other words, almost a fifth of Indian state-run banks’ assets might have soured by March next year.

If the broader economy deteriorates, as many as 10 out of 21 taxpayer-funded lenders could risk falling short of minimum regulatory capital, the RBI says. Don’t be surprised if that happens anyway — even without macroeconomic indicators flashing red.

The gross bad-loan ratio for India’s overall banking system — including public-sector as well as fully privately owned lenders — may rise to 12.2 per cent, the highest in almost two decades, RBI estimates show.

When will this cycle start reversing? Until the nation’s new bankruptcy law grows up a little, big checks from buyers of stranded corporate assets will remain stuck in court proceedings. Meanwhile, the RBI has taken away the various restructuring options banks used as fig leaves to keep classifying dud loans as standard. That welcome rule change could, in itself, test banks’ balance sheets more severely this year than any economic shock in the RBI’s vector auto-regression model.

For India’s banks, 20 per cent NPAs could arrive well before the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. Investors hardly need to summon up visions of an economic dystopia to arrive at that conclusion. – Bloomberg Opinion