New Delhi: The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), announced on the sidelines of the G20 leaders’ summit in New Delhi in September last year, is more than just a grand economic project. It has a lot more to do with India’s geopolitical positioning than pure economic logic.

The project, announced as a part of the Group of Seven’s (G7) Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) to much fanfare, saw the US, the European Union (EU), Germany, Italy, France, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and India signing a memorandum of understanding (MoU), which US President Joe Biden labelled a “big deal” at the time.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar have consistently brought the project to the forefront of the conversation on New Delhi’s foreign policy vision.

In part two of a four-part series on India’s grand vision for connectivity projects, ThePrint will be looking at the IMEC and its strategic place in New Delhi’s plans. The first part gave an overview of all four corridors and why India is pushing for them.

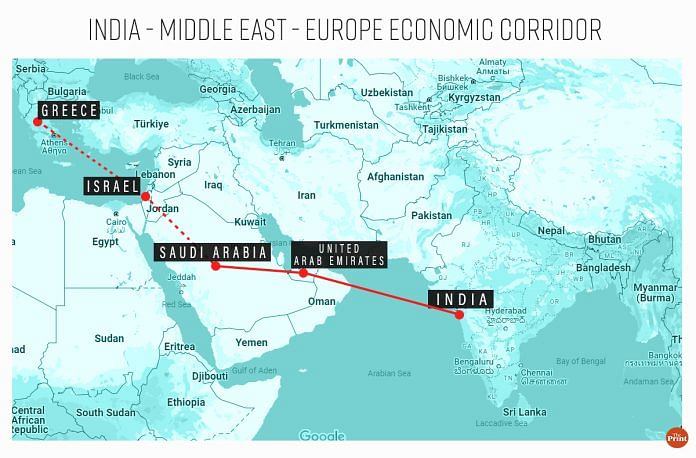

The IMEC project would see goods from the western coast of India travel to the UAE by ship. From there, the goods would be carried by rail through Saudi Arabia and, ideally, reach the Mediterranean at the port of Haifa before being transported to Europe by ship. It would give India a second route to Europe — one that would disentangle the current Suez Canal choke point.

For New Delhi, the IMEC is part of a larger vision of connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific, with India as the bridge connecting the two parts. Jaishankar said as much during a round-table discussion in Tokyo during his visit there in March.

“Connectivity is also acquiring greater salience with new production and consumption centres. India is today working on major corridors, both to its east and to its west,” said Jaishankar during a roundtable discussion in Tokyo earlier in March.

Jaishankar added: “They include, in the west, the IMEC initiative through the Arabian Peninsula and the International North-South Transport Corridor. And to the east, the Trilateral highway in Southeast Asia and the Chennai-Vladivostok route (that) also has polar implications.”

The IMEC has received significant support from two of the West Asian countries, the UAE and Saudi Arabia. However, questions remain over two important connecting points — access to the Mediterranean (via Israel) and the port of entry to Europe.

It is reliably learnt that Israel — which is yet to normalise ties with Riyadh — is keen to be a part of the project, potentially solving the issue of access to the Mediterranean. Greece, meanwhile, has staked a claim as the doorstep to Europe. Neither country is part of the project at the moment.

Also read: India slams China for remarks on Pannun murder ‘assassination plot’

What is IMEC?

The IMEC contains two corridors — the eastern corridor connecting India to the Arabian Gulf, and the northern corridor connecting the Arabian Gulf to Europe. The route across the Arabian Gulf is by rail that would connect the UAE to Israel, via Saudi Arabia and Jordan. From India and Israel, the goods would travel by ship.

According to the MoU signed in September 2023, the railway route will also see the building of allied infrastructure — cables for electricity and digital connectivity, and a pipe for clean hydrogen.

India’s motivation behind the IMEC is not based on “raw economic numbers”, Harsh V. Pant, vice president of studies and foreign policy at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF), told ThePrint.

“Economic numbers would surely look different depending on where you sit. From India’s strategic policy perspective, both the prime minister and the external affairs minister have emphasised linking the IMEC to Southeast Asia, thereby making India a bridge connecting the West to the East,” said Pant.

For Muddassir Quamar, an associate professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Centre for West Asian Studies, the motivation for such connectivity projects, especially in Asia, has always existed but gained prominence after China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) started.

The BRI — touted as the ‘project of the century’ by Chinese President Xi Jinping — envisions a maritime road and a new silk route belt (One Belt One Road) that would connect different regions of the world to Beijing.

“India’s quest for connectivity in the region pre-dates the BRI. For India, logistical and transport connectivity can enhance trade with three different regions — Europe, West Asia, and Central Asia,” Quamar told ThePrint.

Quamar added: “What has happened over the years is that even though the Chabahar Port [in Iran] is functional, India’s quest for access to the Mediterranean has not materialised. The North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) has not worked smoothly.”

This has led India to look for alternative routes, leading to IMEC, said Quamar. He also pointed to a second motivation for IMEC — access to the gas fields of the Eastern Mediterranean.

“Large fields of gas have been found in the Eastern Mediterranean. Smooth connectivity to the region can ensure that India can also import gas from this region. New Delhi’s reliance on gas will continue to grow,” said Quamar.

Also read: ‘Third parties have no right to interfere,’ says China on India backing Philippines

India — bridge between the East and the West

Apart from access to gas and a new trading route to Europe, IMEC as a political project could give India an edge in Southeast Asia — a region where China has spent billions of dollars to gain strategic influence.

“The message of connecting West Asia with East Asia in a large part is to provide a certain resonance or (create) curiosity among the Southeast Asian countries by New Delhi. It offers an alternative to China in the region and thereby reflects India’s positioning of linking IMEC to its eastern transport projects,” said Pant to ThePrint.

The economics of such transnational projects follows geopolitical logic, added Pant.

Quamar added that while there might be some economic sense to the linking of IMEC with other corridors, the likelihood of it working out is “quite high” if there is “political will” behind it.

Political will — at least, within the Arabian Gulf countries — is seemingly quite high. One of the reasons for this, both experts told ThePrint, is that both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are looking to restructure their economies and reduce their dependence on fossil fuels.

Despite the conflict that has broken out in Gaza after Hamas’s attacks on Israel on 7 October 2023, neither Saudi Arabia nor the UAE have announced that they are backing out of the project.

“Earlier, a bold statement like cancelling IMEC would have been made [by countries like UAE and Saudi Arabia] but it has not yet happened. When things settle down in the region, they will look at it again,” said Pant.

In the past few years, Israel has been able to normalise ties with a few West Asian countries, including the UAE and Bahrain, under the ambit of the US-mediated Abraham Accords, which stress peaceful coexistence by ensuring religious freedoms. It is learned that there was a chance of normalisation of ties between Riyadh and Tel Aviv before the current outbreak of violence, as well.

Biden even alluded to IMEC as being one of the reasons for Hamas’s attacks on Israel. India and the UAE signed a framework for IMEC in February 2024, months after the violence broke out in Gaza — a sign that political support for the project remains.

The question of how the final bridge between the West and the East will operate remains. ThePrint has learned that there have been bilateral conversations between New Delhi and Tel Aviv on the project after the outbreak of violence in Gaza. The port of Haifa in Israel is operated by an Indian multinational, the Adani Group, giving more reason to believe that it would be the last stop in Asia before goods are sent to Europe.

However, questions remain over the doorstep in Europe. The Greek port of Piraeus, one of the largest ports in Europe, is owned and operated by a Chinese state-owned company, COSCO Shipping.

There is also the fact that any route around the Suez Canal would affect India’s strategic partner, Egypt.

“Egypt is not only a strategic partner of India, but also a strong partner of the US in the region. The stakes for Washington D.C. are also high and thereby the US may lead efforts to reconcile with Cairo on the IMEC,” said Pant.

This is the second in ThePrint’s four-part series on India’s envisaged transnational transport corridors. Read the first part here.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also read: Modi must find out what Bhutan needs. India can use it to tackle China’s gray zone warfare