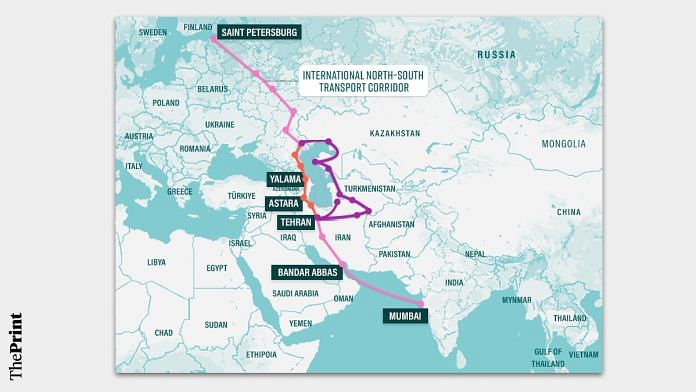

New Delhi: Proposed in 2000, the International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC) was initially meant to transport goods from India to Russia via Iran as an alternative to the conventional Suez Canal route. But geopolitics and administrative issues meant that the proposed corridor went dormant.

Two decades later, the INSTC has become active once again.

Diplomatic sources, government officials, and analysts that ThePrint spoke to point out that the trade boom between India and Russia after the invasion of Ukraine coupled with New Delhi’s vested interests in Iran’s Chabahar Port has brought a once-dormant transport corridor back into focus.

At the time of its proposal, it was an ambitious project: 7,200 km of sea, rail and road lines crossing numerous borders. India was to gain access to the Central Asian and Eurasian markets, while bypassing Pakistan.

Apart from India, Russia and Iran, 10 more countries — Azerbaijan, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine, Belarus, Oman, and Syria — signed onto the project later but implementation waned.

This was due to poor rail connectivity within Iran, less number of return cargoes and burdensome customs clearances at various borders, sources in the shipping ministry told ThePrint.

“When the dry runs were conducted, it was found that streamlining of common clearances at borders was needed — an issue that may affect IMEC (India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor), too. When a cargo goes from a port to a truck and then a rail route, and there is additional paperwork or clearances, it creates a burden on the exporter,” one of the sources said.

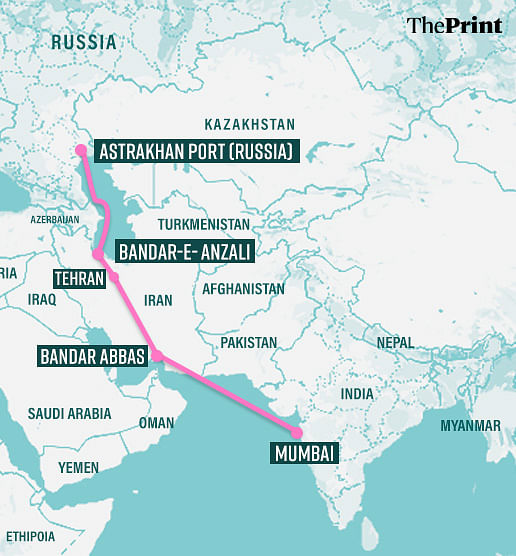

In 2014, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry conducted a dry run from Mumbai to Iran’s Bandar Abbas by sea, Tehran to Bandar Anzali by rail and then by sea onto Russia’s Astrakhan.

Also Read: From East to West, India is making a big push for transnational transport corridors. Here’s why

What brought INSTC back into focus?

Two dry runs were conducted in 2014 and 2017 on two routes to Azerbaijan via Iran and to Russia’s Astrakhan via the Caspian Sea.

The studies thereafter found the INSTC more cost and time effective than the Suez Canal route, according to Shankar Shinde, former chairman of Freight Forwarders Associations in India (FFFAI). Shinde led the 2014 dry run from the Indian side on behalf of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

“We concluded that this was a viable route but insurance, documentation and other issues remained,” Shinde told ThePrint. “But the INSTC has been operational since 2018-19. American sanctions [against Iran] slowed things down, but smaller shipments did flow before July 2022.”

In July 2022, the first major commercial consignment through the INSTC was sent from Russia to India. (The cargo were reportedly wood laminates, not discounted Russian oil primarily being routed through the Red Sea.)

Weeks prior at the Caspian Sea Summit in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, Russian President Vladimir Putin had referred to INSTC as a “transport artery from St Petersburg to ports in Iran and India”.

In the following months, India’s trade deficit would expand sevenfold due to rapid imports of cheap Russian oil — from $4.86 billion in April-January FY 21-22 to $34.79 billion in the same period in FY 22-23.

Reports began to suggest that the INSTC was Russia’s new “economic escape route” in the face of Western sanctions.

“When Iran came under US sanctions in 2019, Indian companies became cautious [of INSTC]. But sanctions against Russia led to a boost in India’s trade with Moscow which brought some positivity back into the conversation about INSTC and revived it in a way,” Gulshan Sachdeva, Professor of European Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, told ThePrint.

Armenia & Azerbaijan’s competing roles

Originally, the INSTC was viewed as a potential way to route goods to Europe through Russia, though that has been dampened after Moscow launched its war against Ukraine.

“The Europeans are probably not in favour of such linkages with Russia. That’s where Armenia comes in,” said Sachdeva.

Armenia has been proposing a corridor from Mumbai to Bulgaria’s Varna through the Black Sea. This helps Armenia bypass its regional adversary, Azerbaijan.

This corridor builds on Iran’s idea of a Persian Gulf-Black Sea Corridor, first proposed in 2016. It would be in the opposite direction of goods flowing to Central Asia via the Caspian Sea, and would not involve Russia.

According to the Armenia Embassy in India, inclusion of the Chabahar Port in the INSTC makes sense for the Mumbai-Varna route that Armenia is pitching as a corridor to Europe.

“The development of the Chabahar fits well into the logic of creating a viable alternative route to Europe. This route connecting Asia with Europe can boost connectivity and trade among the participating sides, by connecting India, through the Bandar Abbas and Chabahar ports in Iran, to Bulgaria, Romania, Greece and further,” the embassy told ThePrint in response to a media query.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan has become further entrenched in the INSTC. Not only Azerbaijan enjoys a highway connection with Iran, Russia is funding and helping build the “missing link” connecting Azerbaijan and Iranian railways. This is about 170 km of rail between Rasht (Iran) and Astara (Azerbaijan), construction for which is set to commence this year.

India has been growing closer ties with Armenia, built on its support to New Delhi on the Kashmir issue and the growing Indian arms shipments to the South Caucasus country. India, Armenia and Iran have also forged a trilateral in contrast to Azerbaijan, Turkey and Pakistan’s grouping.

However, experts question if India’s relations with Armenia could hurt its INSTC ambitions.

In a piece for The Diplomat, Seamus Duffy, research associate at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, calls India’s position in the South Caucasus “inflexible”.

“India has not been shy in supporting Armenia with limited arms imports. India’s plans for the completion of the INSTC in fact hinge on such support…[else] it would likely have to complete the INSTC with the help of Pakistan-allied Azerbaijan,” he explains.

China has also been making progress on the “Middle Corridor” — a multimodal transport route between Beijing, Central Asia, Caspian and Black Sea basins — launched in 2014. It is officially known as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR).

Last month, a container train from China’s Xian arrived in Azerbaijan’s Absheron using this route. It went through Kazakhstan and the Caspian Sea in just 11 days as opposed to the usual one-month window. But challenges remain for Beijing, explains historian and lawyer Arunansh Goswami.

“The ‘Middle Corridor’ will help China a lot economically, but keeping in mind China’s ‘East Turkistan (Xinjiang)’ problem, a corridor which includes several Turkic countries along with China may not be viable in the long-run,” said Goswami, who participated in the first Indo-Armenia Dialogue on the sidelines of the Raisina Dialogue this year.

Importance of Chabahar Port

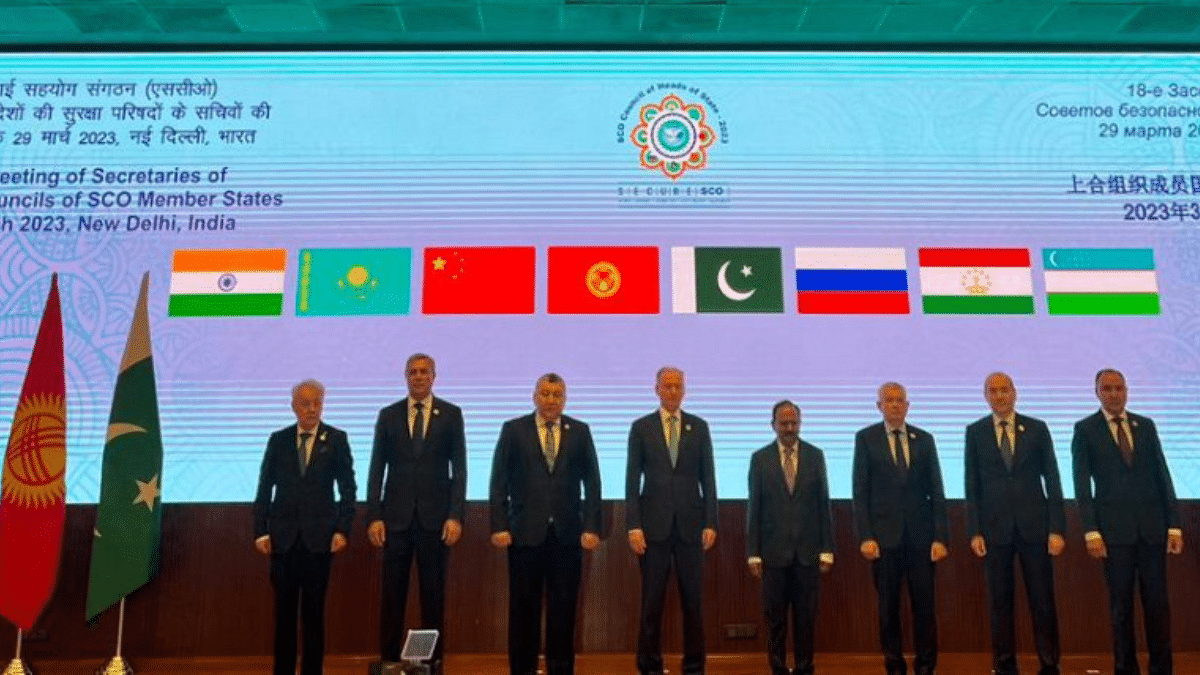

While Bandar Abbas has been Iran’s busiest port, India has long been pushing for the Chabahar Port to be linked to the INSTC as well. Last March, National Security Advisor (NSA) Ajit Doval reiterated that India would like Chabahar to be included in the framework of the INSTC, while speaking at an NSA-level meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in Delhi.

Unlike Bandar Abbas, Chabahar is located closer to India’s west coast and is a deep-sea port that can take full-size container ships. India has invested in one of two ports at Chabahar — Shahid Beheshti. It has committed about $500 million towards development of this port since 2016.

Operated by the state-owned India Port Global Limited (IPGL), Shahid Beheshti is also strategic as it has been used to ship Indian humanitarian goods to Afghanistan, bypassing the land route through Pakistan.

According to Shinde, India conducted a dry run project in 2020 via Chabahar for “seamless borderless movements” and for compliance with the Transports Internationaux Routiers, International Road Transport (TIR) system.

Both India and China seek to use Chabahar for their own strategic interests. Pakistan’s Gwadar port, funded by Beijing as part of China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), is located merely 100km away from Chabahar.

Meanwhile, India and Iran have been close to finalising a long-term contract for the strategic port.

Sources in the Iran Embassy in India told ThePrint that the deal could be signed “within weeks”, which could increase the “speed of goods transit” and the “capacity of the INSTC”.

That said, INSTC is yet to fully materalise fully on ground.

“Indian exporters still face challenges. Banks are hesitant to touch any goods that transit through Bandar Abbas due to sanctions [against Iran]. There also aren’t enough large freight forwarders to ensure quick movement of cargo across the multiple modes of transport,” explained Ajay Sahai, Director General & CEO of the Federation of Indian Export Organisations (FIEO), which functions under the commerce ministry.

This is the third in ThePrint’s four-part series on India’s envisaged transnational transport corridors.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: IMEC — bridge between East and West, as well as India’s queen’s gambit against China