Informed opinion might see demonetisation as a reckless disaster, but in Indian politics, this consensus does not matter.

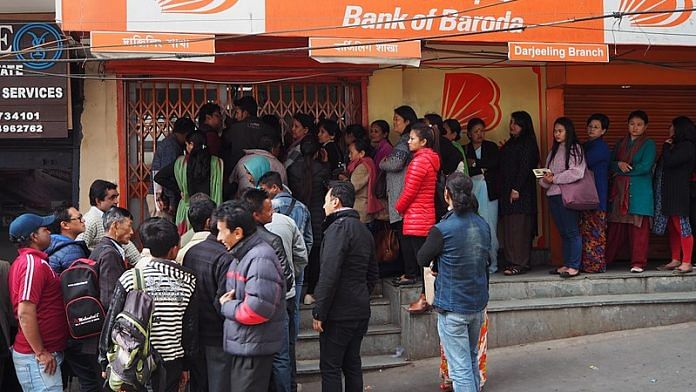

A year after Prime Minister Narendra Modi suddenly extinguished nearly 90 per cent of India’s currency by value by invalidating the country’s two highest denomination currency bills, Indians are still debating the merits of the move.

At this point, the economic consensus — barring a handful of experts with close links to the Indian government or the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party — appears overwhelming. Demonetisation, as the policy is popularly known, was a risky and destabilising move that caused vast economic damage for little tangible gain. But viewed through a political prism things look quite different. Far from punishing Modi, voters have rewarded him. This apparent paradox has potentially serious implications for economic policymaking in India.

For now, the left-of-center opposition Congress Party — whose own record in office (2004–2014) was hardly stellar — has launched a spirited attack on demonetisation on its first anniversary.

In the Financial Times, party scion Rahul Gandhi, criticized Modi’s “arbitrary and unilateral” decision that, instead of wiping out corruption as advertised, has wiped out “confidence in our once booming economy.” In a rare interview, former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, an Oxford-trained economist, called demonetisation a “catastrophic economic policy,” and a “monumental blunder” whose “turmoil was entirely self-inflicted.”

These criticisms largely echo those of the vast majority of prominent experts who have written about demonetisation over the past year. Former World Bank chief economist Kaushik Basu invoked Adam Smith, and accused the Modi government of ignoring the laws of economics and intervening in the market with “a blunt and heavy hand.”

Former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram Rajan, with characteristic understatement, said that “there were potentially better alternatives” to achieve the policy’s main goals. Modi initially listed these as fighting corruption, black money, and counterfeit currency used to fund terrorism.

Harvard’s Larry Summers, who has long advocated the abolition of the $100 note and the 500 Euro note, pointed out that free societies do not generally pursue expropriation. Steve Forbes called the move “breathtaking in its immorality.” Berkeley’s Pranab Bardhan described it as “one of the grandest hoaxes in Indian political history.”

By contrast, support for demonetisation among experts has been thin on the ground. A month after the decision, Columbia University’s Jagdish Bhagwati and Johns Hopkins’s Pravin Krishna hailed it as a “courageous and substantive economic reform” with “the potential to generate large future benefits.” More recently, however, Bhagwati and Krishna, along with Carleton University’s Vivek Dehejia, have struck a somewhat more cautious note, conceding that based on the “rationale originally advanced” it “would at best be unclear” if demonetisation can be counted as a success.

Suffice to say that the weight of informed opinion leans heavily toward viewing demonetisation as a reckless disaster that slowed economic growth, caused widespread job losses, and dented the institutional credibility of India’s central bank. It has also, as I wrote in the Wall Street Journal last year, tarnished Modi’s reputation as a sound economic manager.

Here lies the rub: In Indian politics, this consensus does not matter. For the most part, voters take a dramatically different view from economists on demonetisation. Critics may point out that only 6 per cent of India’s black money (illegally untaxed income) is held in cash, and that most of it found its way back to the banking system anyway, belying early hopes of a massive government windfall. But for many ordinary Indians demonetisation remains a shining example of an incorruptible leader striking a bold blow against corrupt elites. As their logic goes, those who complain about it must be corrupt themselves.

This realization deepened for me earlier this year, when I traveled in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh ahead of an important state election that Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party ended up winning in a landslide.

Of the scores of people I asked about demonetisation — one of my pet obsessions, as anyone who follows me on Twitter can attest to — many readily admitted to suffering personally in its aftermath. I heard stories from auto drivers who skipped meals to feed their children and shopkeepers who put off family weddings. But the vast majority of those I spoke with — including those who suffered — said they approved wholeheartedly of the policy. Many were convinced that Modi had grievously wounded the rich. Others thrilled to the sight of such a “bold move.”

What does this mean for India? If you’re an optimist, you can hope that Modi has learned his lesson and will never again attempt to pull off such sweeping change without expert advice. But pessimists can draw the opposite lesson. In the world’s largest democracy, good economics is not necessarily good politics. In fact, the opposite is sometimes true. As Modi’s political juggernaut shows, even deranged economic decisions can be followed by smashing electoral success.

Sadanand Dhume is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

This article originally appeared on the American Enterprise Institute website.

Mr. Dhume,

To address your question “What does this mean for India? ” –

1. It means that the future is bleak indeed. It means that future policy decisions will follow the same course and let emotion trump basic logic.

2. It’s political success ensures that DeMo is very likely going to be repeated, perhaps on a grander scale for a larger impact. Say to demonetize 99% of all currency.

3. It means that the biggest winner from DeMo – is Pakistan. The Pakistani person who came up with the idea of paying “stone throwers” must have got a medal of honour. For a paltry investment of paying 50-60 kashmiris to riot, the ROI was to get all India shut down for months!

4. It means that India’s influence in Nepal and Bhutan – countries that accept INR – will diminish. They would be wary of Indian currency in future, leading to increased Chinese influence.