The Gender Budget Statement shows Rs 31,390 crore allocated to women-only schemes, but over two-thirds of these are generic schemes like the PM Awas Yojana.

The Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party are once again locked in a war of words over women’s reservation.

Successive central governments headed by both parties have talked a big game when it comes to women’s empowerment. But when it has come to putting their money where the mouth is, they have only ended up paying lip service.

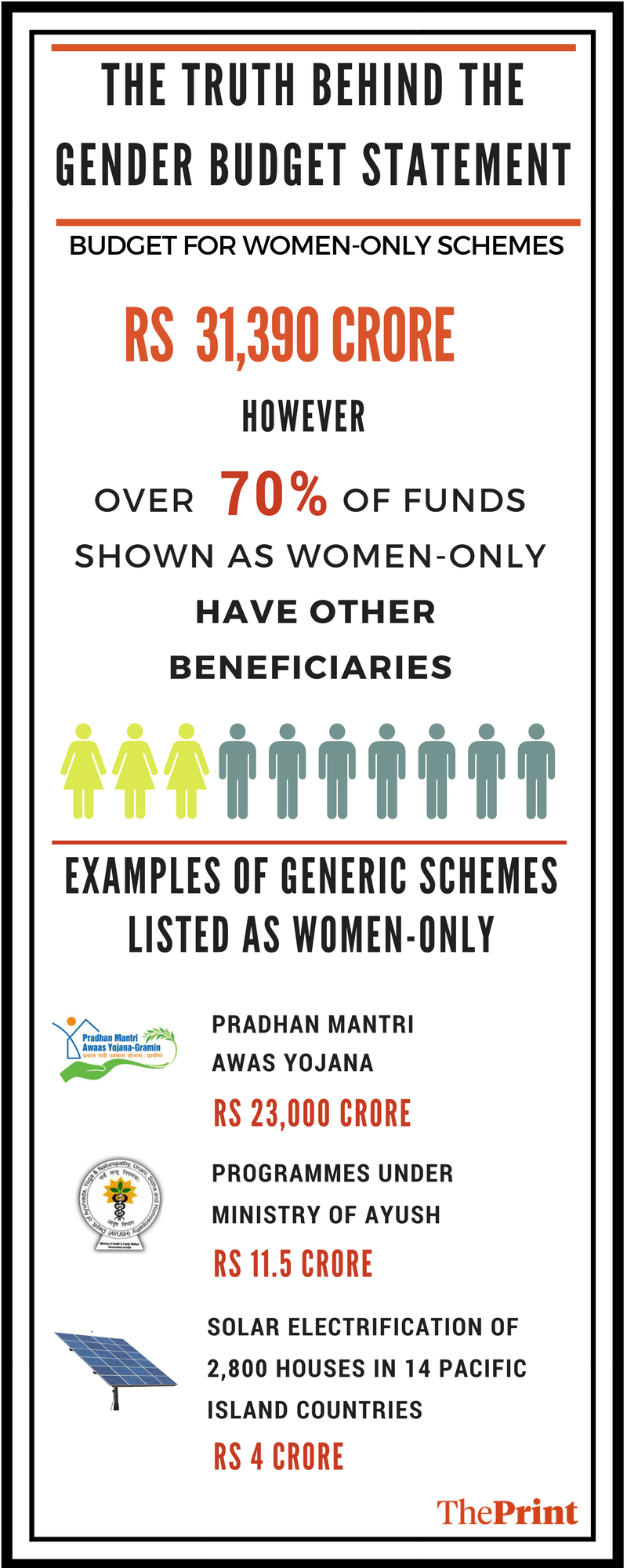

According to the Gender Budget Statement (GBS) for 2017-18, the Centre claims Rs 31,390 crore has been allocated for women-only schemes.

But scratch the surface, and it turns out that Rs 23,000 crore of this amount actually belongs to the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) – a scheme that isn’t women-only as it also serves manual scavengers, primitive tribal groups, legally-released bonded labour groups, and members of the SC/ST communities.

Similarly, programmes under the ministry of AYUSH, such as the Central Council for Research in Unani Medicine, the National Institute of Siddha (NIS), the Central Council for Research in Siddha, and the Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences, are also included as ‘women-only’ schemes in the GBS.

Also included is a scheme under the external affairs ministry for the “solar electrification of 2,800 houses in 14 Pacific island countries to empower women”.

And it’s not just Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP government that is in the dock. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s UPA-I government, which introduced gender budgeting to India in 2005-06, was also guilty of the same.

While experts say that the exercise had relatively more momentum under the UPA regime, there were instances of non-women-exclusive schemes being enlisted under the 100 per cent women beneficiary section before the Modi government took charge as well.

In the 2013-14 GBS, a sum of Rs 15,184 crore allocated to the Indira Awas Yojana, was listed under the 100 per cent women beneficiary section.

A worrying sign

Gender budgeting is an internationally-recognised tool to bring benefits of development to women.

It recognises that various sections of society benefit from the national budget differently, depending on their socio-economic positions. It entails dissecting government budgets to determine its gender differential impacts and to ensure that gender commitments are translated into budgetary commitments.

For instance, if the government is seeking to expand primary education, it ought to take cognisance of the lower enrollment rate among girls vis-a-vis boys, and introduce steps to balance the rate. Typically, the steps taken by the government to this effect will fall under gender budgeting.

However, experts point out that while all formal mechanisms are in place, gender budgeting is something only done on the side in the women and child development (WCD) ministry, without any rigour or momentum.

An official in the ministry, the nodal agency for gender budgeting, was evasive when asked why the PMAY, for example, was listed as a women-only scheme. The official sought to divert the question to the rural development ministry, saying the latter supplied the data and could possibly have disaggregated numbers.

When asked to explain how this sum was actually utilised to benefit women, the WCD ministry official said “all schemes percolate down to different sections of society”.

The ministry’s nonchalance is a huge problem, because as the nodal agency, it needs to actively review the outcomes of the gender budget, and disaggregate the data on expenditures. Instead, it is merely taking the rural development ministry’s data on the PMAY at face value, and dumping it en masse into the women-only section of its GBS.

However, it is not completely the WCD ministry’s fault either.

Paromita Majumdar, who was associated with the ministry as a consultant specifically responsible for supervising gender budgeting, said the “ministry is given no authority to actually implement gender budgeting in its true form”.

The finance and WCD ministries are required to work in tandem for gender budgeting, yet the attitude in the finance ministry is that of a “big brother”, she said. “There is no rigour, no momentum. We’ve really diluted things under the present regime,” Majumdar added.

An international body which closely monitors gender budgeting in the country also agreed that there is a general attitude of negligence in the ministry.

Bangladesh shows the way

While gender budgeting is a complex process, it is easily achievable with some concerted inter-ministerial effort.

For example, if there is a scheme which the home ministry has listed as a women-exclusive scheme, both the finance ministry and WCD should coordinate to ensure the amount is not just sanctioned, but also utilised, and actually reaches women on the ground.

In Bangladesh, for instance, a holistic mechanism is in place. Gender issues are embedded in the ‘Medium Term Budget Framework’, which is used to prepare the national budget. But this is followed up with rigorous monitoring.

A model has been developed, wherein all expenditures are disaggregated to indicate what percentage of allocated funds benefit women.

Further, a gender budget report is published alongside the budget, which explains how activities of different ministries have fared in empowering women.

In India, on the other hand, information on gender budgeting in the nodal ministry itself is glaringly lacking.

As Majumdar puts it: “It’s unfortunate that the little momentum gained by gender budgeting has faded away and the role of the gender budget statement, for all its potential, has been restricted to a budget circular in India.”

Editor’s note: This report has been updated to correct the reference to an international organisation critical of the Women and Child Development Ministry’s handling of gender budgeting.