Bangkok: Over the past few decades in Thailand, a crackdown or coup would eventually bring an end to street protests and life would more or less go back to normal until the next round of demonstrations.

But this time the Thai establishment has a bigger problem: The student-led protest movement doesn’t want power for itself — it wants to fundamentally change a political system that has seen about 20 military coups since 1932. And they also aren’t afraid to criticize the monarchy, the lynchpin that holds the system in place.

Discussing the monarchy openly has long been taboo in Thailand, where insulting senior members of the royal family is punishable by as many as 15 years in prison. The new space where some feel comfortable criticizing King Maha Vajiralongkorn started on social media before spreading to the streets, and the royalist establishment led by Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-Ocha is now struggling to shut it down.

His government this week imposed an emergency decree banning large gatherings, arrested key protest leaders and took action to stop the “disrespect” of the royal institution. Prayuth, a former army chief who led a 2014 coup, said Friday that he wouldn’t resign and would lift the emergency decree ahead of its expiration in 30 days “if the situation improves.”

“The country needs to have stability to deal with the economy that’s been hit by the pandemic,” he told reporters, adding that the protests had become “severe.” Some 51 people were arrested in demonstrations this week, according to the Thai Lawyers for Human Rights.

Hong Kong Style

Protesters turned up in large numbers in defiance of police on Thursday night, and have vowed to continue demonstrations. In a letter from jail after his arrest this week, protest leader Parit Chiwarak called for continued pop-up gatherings throughout the country. He said protesters should remain flexible and avoid staying overnight at one place — mirroring tactics used recently in Hong Kong and other parts of the world.

The government now may need to take more aggressive steps to stop them, raising fears of another deadly military crackdown similar to what Thailand saw in 1973, 1976, 1992 and 2010 — particularly as groups of royalists organize to confront the pro-democracy demonstrators. Even if they stop the movement on the streets, authorities would still need to find some way to quash the discussion on social media and address grievances over perceived inequality, corruption and abuse of power that have fueled support for the protests.

“Because this movement started on social media, the momentum of the movement remains there,” said Titipol Phakdeewanich, dean of the political science faculty at Ubon Ratchathani University in northeastern Thailand, adding that new leaders would emerge as others are arrested. “The government’s strategy could backfire and end up bringing out more people to join the movement.”

Sluggish Economy

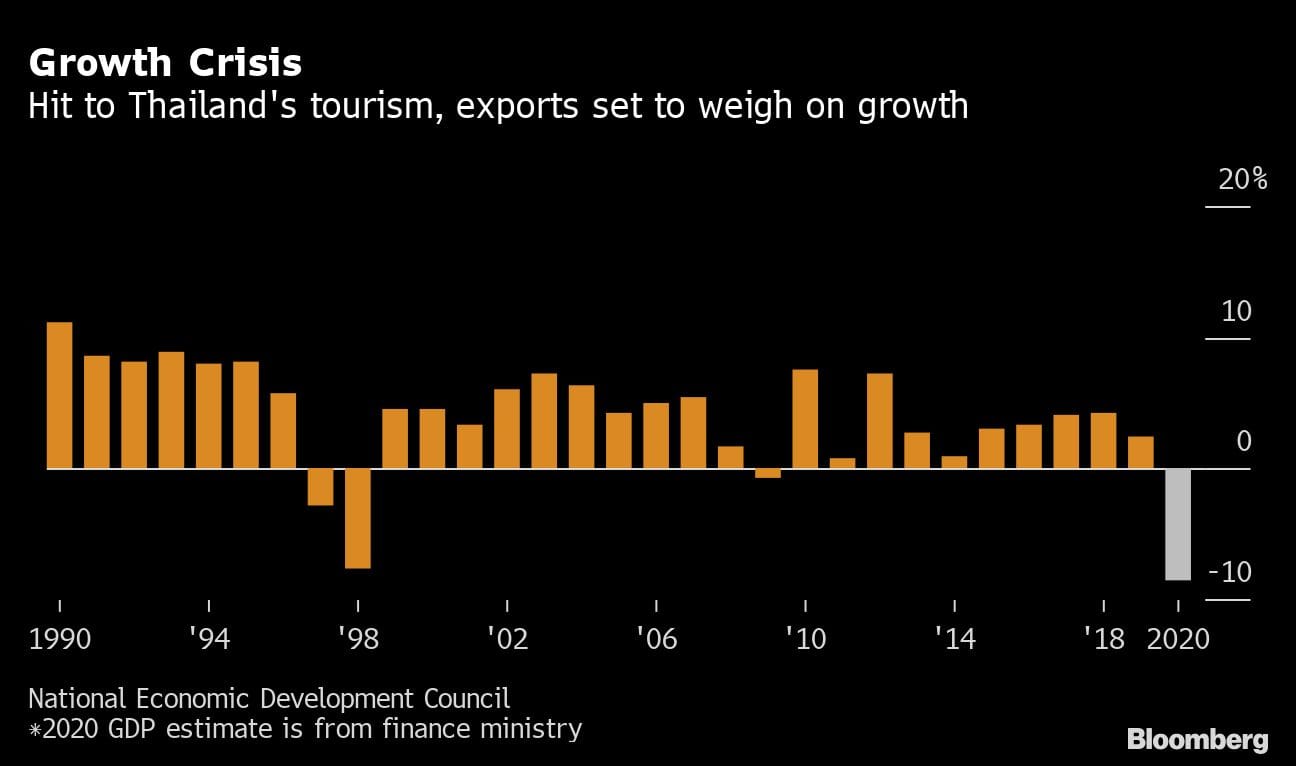

The protests are underpinned by years of sluggish growth now exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, which has put the Thai economy on course for its worst performance ever by derailing the two main drivers: tourism and trade. The benchmark SET Index of stocks has lost 21% this year.

Those economic woes have put a bigger spotlight on the divide between rich and poor. The World Bank said in March that the number of Thais living in poverty had climbed in recent years, while a study released last year by the Bank of Thailand’s research institute found that about 36% of corporate equity is concentrated in the hands of just 500 people.

Vajiralongkorn’s wealth in particular has become a source of resentment, with protesters demanding more control over royal assets that include extensive landholdings in downtown Bangkok and sizable stakes in two of Thailand’s biggest listed companies: Siam Commercial Bank Pcl and Siam Cement Pcl. They have also increased scrutiny of public funds used to finance the king’s lifestyle, this week shouting “my taxes” when giving the three-finger salute — a symbol of the demonstrations — to a passing motorcade carrying Queen Suthida Bajrasudhabimalalakshana.

‘Genuine Grievances’

Many young people in particular are joining the protests because they don’t see a viable economic future and they have “genuine grievances” over how the country has been run under a Cold War-era political system that gives more power to the military, monarchy and judiciary than elected politicians, according to Thitinan Pongsudhirak, director of the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.

“If you ask who is backing them, well, their grievances are backing them,” he said. “Putting an end to these grievances requires some accommodation and some concessions and some change and reform. And we’re not seeing that — we’re only seeing the contrary.”

Although the protesters aren’t backed by any specific political group, the pro-democracy camp in parliament has condemned moves to silence them. Pheu Thai, the largest opposition party, said in a statement Thursday that the government should immediately lift the state of emergency and release the arrested protest leaders. The political group linked to Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, a banned opposition leader who has been among the most vocal critics of the monarchy, planned to help bail protesters out of jail.

Charter Changes

Those parties have also spearheaded attempts to rewrite the constitution, one of the main protest demands along with the resignation of Prayuth and a host of changes to the monarchy designed to make it more accountable to Thailand’s 69 million people. The government has said it’s open to some unspecified changes in some areas of the charter, which was drafted by a military-appointed panel and helped Prayuth remain in power after last year’s election.

But the majority coalition that backs Prayuth has delayed that process. The establishment has a long history of undermining attempts to introduce reforms that would give real power to elected officials, and analysts are skeptical it’s anything more than a way to delay action until the current wave of anger subsides.

“The government will probably use the promise of charter amendments and referendum — a timely affair — as a token way to bide its time and outlast the demonstrators, while in fact it makes little, if any, changes,” said Paul Chambers of Naresuan University’s Center of Asean Community Studies, who writes frequently about Thailand’s military.

No Concessions

Prayuth himself has shown no sign of resigning and has avoided directly addressing demands related to the monarchy, which include prohibiting the king from endorsing any coups and revoking restrictive lese majeste laws. Thanakorn Wangboonkongchana, a secretary to the minister attached to the prime minister’s office, said “Thai people couldn’t put up with” the actions of the protesters, calling them “disrespectful of the monarchy.”

“The monarchy is loved and respected by Thai people,” he said in a statement Thursday. “The government has to stop those actions.”

The protests are starting to gain traction globally. Thailand on Friday blocked the website change.org after a petition calling for Vajiralongkorn to be declared persona non grata in Germany, where he spends the bulk of his time, gained more than 100,000 signatures. German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said this month that Thailand’s king shouldn’t be conducting state business from the European country.

Prayuth’s administration hasn’t shown any willingness to compromise and clashes are possible going forward, according to Kevin Hewison, an expert in Thai politics and an emeritus professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“The government probably thinks that if they arrest a few people, keep them in jail and crack a few heads that’d be enough,” he said. “But that’s probably not the case with this group. Watching 15-year-old girls in school uniforms climbing out of the barricade to stand in front of the police — that’s something I haven’t seen before in Thailand.” – Bloomberg

Also read: How Covid gives Thailand national parks a chance to recover from damage caused by tourism