New Delhi: Faced by default of loan obligations by countries which are partners in its ambitious global Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has had to reportedly develop a system of bailing out these nations, which already owe it huge sums of money and are now financially distressed.

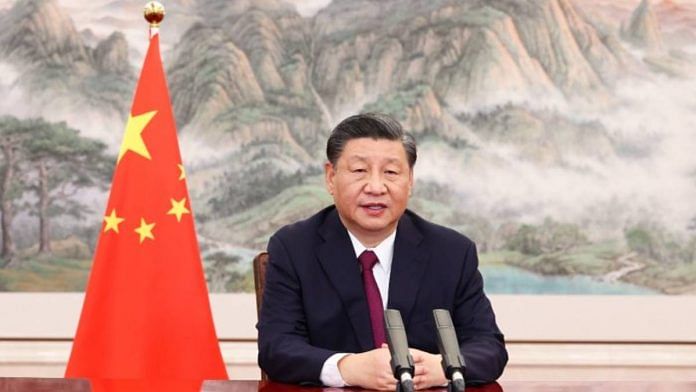

More than 150 countries, many of them developing and emerging economies, are part of President Xi Jinping’s BRI — touted as the “project of the century” — which envisages new trade routes connecting China with the rest of the world and includes construction of ports, roads, railways, airports and other infrastructure.

Since 2013, when the BRI was launched, China has lent huge sums of money to many of the partner nations for the development of the large infrastructure projects which are part of the initiative. A report published in Financial Times in April, pegged the BRI lending figure over the past decade at approximately $1 trillion.

With the Covid pandemic hitting many of these debt-burdened nations hard, China has had to renegotiate or even write off debts to the tune of $76.8 billion between 2020 and 2022, data released in March this year by the Rhodium Group, an independent research provider, has shown.

Additionally, China has had to provide emergency funding to some of these distressed nations, through global swap lines and rescue loans, to the tune of $185 billion between 2016 and 2021, noted a March 2023 paper by researchers from the World Bank, AidData, Harvard Kennedy School and Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

The paper pointed out that “as of 2022, 60 per cent of China’s overseas lending portfolio supports debtors in distress, up from just 5 per cent in 2010”.

These numbers, however, may just be the tip of the iceberg.

According to another paper published in 2021 by researchers from the World Bank and Kiel Institute, the “size and characteristics of China’s lending boom have remained exceptionally opaque”.

Srikanth Kondapalli, dean, School of International Studies, and professor of China studies at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), told ThePrint: “No official numbers have been released by China about the amount of money lent by the government. Countries signing MoUs [memorandum of understanding] with the nation or Chinese banks, such as Industrial and Commercial Bank of China or Export-Import Bank of China, cannot tell anyone of their loans.”

Researchers from the University of Munich, Harvard Kennedy School and the Kiel Institute have also highlighted that around 50 per cent of Chinese lending is not included in the World Bank database. This is problematic when understanding the total debt of a country, especially in a default.

For instance, Zambia became the first African country to default on its debt obligations post the Covid pandemic in late 2020. According to a September 2021 Reuters report, it was later found that Zambia’s debt to China was nearly twice the official estimate.

China experts ThePrint spoke to said emerging and developing economies are induced to look at the nation for funding of projects that other international lenders might ignore, also because it’s often easier to get loans from China than from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or World Bank.

For China, the loans are an important geo-political tool, often involving significant trade-offs with the receptors, the experts added.

In a press briefing in March, however, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Mao Ning had strongly rejected the idea that Chinese loans are “debt traps” or “opaque loans”, stating, “China has always carried out investment and financing cooperation with developing countries based on the principle of openness and transparency”.

“We never force others to borrow from us or forcibly ask any country for debt repayment. We never attach any political strings to loan agreements, or seek any selfish political interests,” she added.

Also Read: Chinese provinces built big-ticket infra on debt. Now a $23-tn crisis threatens to derail Xi’s BRI

Why do countries borrow from China?

Ritu Agarwal, associate professor at Centre for East Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, explained: “China started lending through concessional loans in the 1990s, looking to take over as the developing world’s chief lender, without requiring the same due diligence as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or other lenders.”

Gunjan Singh, assistant professor at O.P. Jindal Global University, added that “smaller nations go to China because Beijing has always been keen to extend loans without looking for guarantees of repayment, as well as ignoring the domestic realities of the recipient nation”.

Organisations like the IMF, World Bank and the Paris Club have certain principles based on which they lend to countries, specifically understanding their debt servicing capabilities, Kondapalli said.

Chinese lending, on the other hand, functions on different principles. “What China gets from these loans is unclear in each case, given that none of the agreements are made public. But there are strategic reasons behind it for the communist nation,” he added.

Chinese strategy behind lending

Loans are a strong geo-political tool for Beijing, said Singh.

“The Chinese image has changed over time to one where Beijing is ready to invest or provide loans, but it is using these loans to extend its influence as well as geo-strategic presence,” she explained, adding that “China has always provided loans at higher rates than other international financial institutions”.

The idea of an image makeover is not new. “China’s ‘peaceful rise’ was an official policy undertaken by former president Hu Jintao”, according to Agarwal.

“The idea behind the ‘peaceful rise’ was to remake China’s image as an alternate model of prosperity, as well as create conditions for economic interdependence between China and third countries,” she said.

According to the experts on China, the nation had joined the IMF as a debtor in the 1980s before recasting itself as a lender and partner of the developing world. Borrowing from China was made much easier than from other institutions.

“Loans (from other institutions) have to be passed or approved by all member nations. And the main goal is that the loans need to be beneficial to the receiving countries. The level of scrutiny and guarantees make these loans appear slower and less successful,” Singh pointed out.

The trade-off

While Chinese lending terms are usually hidden, the March 2023 paper by researchers from World Bank, AidData, Harvard Kennedy School and Kiel Institute mentioned earlier put forth data on certain loan agreements made with China, and the collateral put forth by the borrowing country.

In 2016, Angola received a $6.9 billion loan from China Development Bank while offering “unspecified income from oil exports” from Sonangol, Angola’s state-owned petroleum and natural gas company, as collateral.

A $10 billion loan to Venezuela in 2015 was backed by Petróleos de Venezuela income from daily oil sales to China National United Oil Corporation. Petróleos de Venezuela is a state-owned enterprise of the Venezuelan government.

“China’s lending strategy in cases like Angola or Sri Lanka was planned with a view of their strategic resources,” explained Kondapalli.

“China’s interest in Sri Lanka was the Hambantota International Port. Despite India’s $3 billion support to Sri Lanka last year at the height of its financial crisis, the government of Sri Lanka allowed the Chinese spy ship Yuan Wang 5 to dock at Hambantota,” he added.

China’s usage of loans as leverage has not gone unnoticed.

“After the Hambantota development, smaller nations have become more careful and want to be thorough about the loans promised by China,” said Singh.

Nevertheless, this leaves questions about the future of the global economy, given the financial distress faced by economies around the world. As the study by researchers from the World Bank and Kiel Institute noted: “If history is any guide, multi-year debt workouts with serial restructurings lie in store.”

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: No investment in Russia, dip in Pakistan, pivot to Saudi — China’s BRI takes a turn