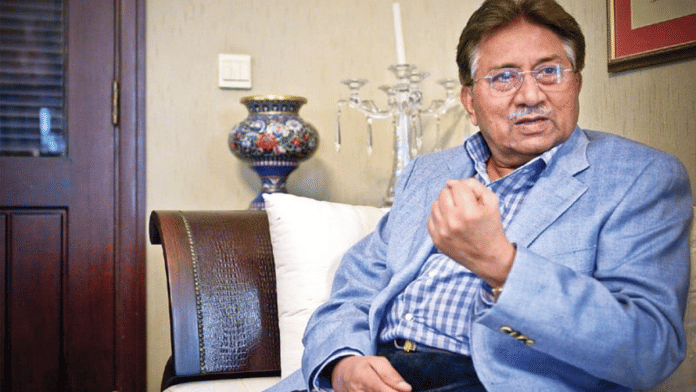

New Delhi: “The Chief cut the Gordian knot: ‘Enough!’” the great writer Maria Vargas Llosa wrote of some other despot, in another land. “Great ills demand great remedies.” Even though he was not known to have been fond of reading literary novels, the sentiment would likely have the approval of General Pervez Musharraf, who passed away at a Dubai hospital on Sunday at the age of 79, after a long battle with cancer fought mainly in exile from his homeland.

Like Lllosa’s tyrant, General Musharraf forgave his own sins: His autobiography casts his 1998 military coup as having saved Pakistan from corrupt politicians, and takes credit for having steered the country through the treacherous years following 9/11.

His critics will, most likely, remember another General: one responsible for large-scale human rights violations, including extra-judicial executions; fuelling jihadist fires; the overthrow of the Constitution, which led to a death sentence for treason.

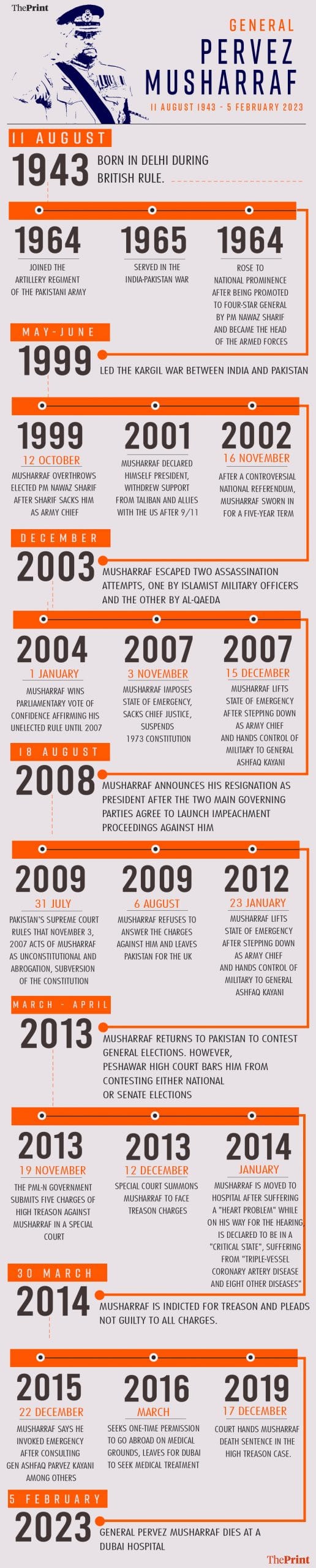

Born in 1943 to the civil servant Syed Musharrafuddin and his wife Zarin Musharraf, the youngest of three brothers, the man who went on to become army chief and president, migrated from India to Pakistan at age four. His upbringing was westernised: His Aligarh Muslim University-educated father, and Indraprastha College-educated mother, at one point kept a dog they called Whiskey.

Following some years in Turkey, the family moved back to Pakistan in 1956. Musharraf studied at the Forman Christian College University, before joining the Pakistan Military Academy at Kakul, aged 18.

Like many military officers of his generation, Musharraf served in the India-Pakistan war of 1965, and fought with the élite Special Service Group in 1971. He commanded a Brigade in operations along the Siachen glacier—without success—in 1987. That battle became something of an obsession: In 1988-1989, he presented a plan to then-prime minister Benazir Bhutto to recapture the glacier by taking Kargil. He was rebuffed.

In 1998, Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif sacked army chief, General Jehangir Karamat. In search of a pliant successor, Sharif picked Musharraf bypassing two more-senior candidates, Lieutenant-Generals Ali Kuli Khan and Khalid Nawaz.

The choice was to prove a bad one. Musharraf executed his long-cherished Kargil plan in 1999, by some accounts without the knowledge of his prime minister. Nawaz sacked his army chief — even as the general was on a flight home from Sri Lanka — precipitating a coup. The prime minister ended up in prison, and then exile. The general became his country’s leader.

Following Kargil, levels of violence in Kashmir surged — a sign that the general wasn’t giving up on his anti-India agenda. Then, 9/11 happened, and the United States threatened to bomb Pakistan “into the stone age” unless it helped bring down the Taliban.

General Musharraf proved successful at playing both sides in the game that followed. He continued to support the Taliban, and some allied jihadist factions. At the same time, he provided logistical and intelligence support to the US. Like all double games, though, this was a perilous one: The jihadists he double-crossed mounted multiple assassination attempts, and stepped-up violence against the Pakistan Army.

Even as these events unfolded, Jaish-e-Muhammad jihadists attacked Parliament House in 2001, sparking off an India-Pakistan crisis. General Musharraf succeeded in deterring India from going to war, by threatening it would escalate into a nuclear conflict. He soon realised, though, that even the crisis imposed asymmetric costs on Pakistan.

Lieutenant-General Moinuddin Haider, one of Musharraf’s closest advisors, was to later recall telling him: “Your economic plan will not work, people will not invest, if you don’t get rid of extremists.”

Haider was backed by other influential figures, including former intelligence chief Lieutenant-General Javed Ashraf Qazi. “We must not be afraid,” General Qazi said in the wake of the 2001-2002 India-Pakistan military crisis “of admitting that the Jaish was involved in the deaths of thousands of innocent Kashmiris, bombing the Indian Parliament, (the journalist) Daniel Pearl’s murder and even attempts on President Musharraf’s life.”

To end the conflict with India, Musharraf launched an ambitious programme of secret diplomacy, first with Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The plan came within a hair’s breadth of success.

Fearing Musharraf’s policies were leading to internal crisis and a showdown with their long-standing Islamist clients, the Pakistan Army’s leadership quietly helped ease him out of military office in 2007. Events rapidly spiralled downwards. In 2007, amidst a showdown with the judiciary, he was forced to impose an emergency. Later that year, former prime minister Benazir Bhutto returned home, only to be assassinated in an attack which a United Nations investigation later suggested had official complicity.

In 2008, the new Pakistan People’s Party-Pakistan Muslim League government impeached Musharraf, and forced him into exile — just as he had done with Sharif. Following nine years in the president’s palace, Musharraf moved to a three-room apartment off Edgware road, worth an estimated £1 million — modest by the standards of Pakistan’s élite. The smells and sounds of London’s ethnic-Arab quarter — kebab shops and shisha-bars — accompanied the general as he left home occasionally, for a game of golf or dinner at the Dorchester.

General Musharraf returned to Pakistan three years after he left, but his hopes of a political career ended in ruins. In 2013, he was placed under house arrest. The next year — likely because of his close personal relationship with Army chief General Raheel Sharif — he was allowed to leave the country for medical treatment.

The last years of General Musharraf remained shadowed by the legal fallout from his years in office. In December 2019, a special court declared him a traitor and sentenced him to death in absentia for abrogating the Constitution and declaring an Emergency. The conviction was later annulled, but Musharraf could never return to his homeland.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Pakistani leaders want to ‘reimagine’ the nation but must cut lavish defence spending first