New Delhi: For over two decades, Pakistan’s most famous real estate tycoon Malik Riaz flew high. As the go-between for the country’s military and political elite, he enjoyed unparalleled connections, but then flew too close to the Sun.

He built an empire that competed with the army in its favourite business, fought and won a legal battle with the navy over the use of their name ‘Bahria’, and seemingly drove a wedge between the two forces. Now, sitting in Dubai, the chairperson of Bahria Town is persona non grata in Pakistan, with his assets frozen, and cut to size by the army he was once in bed with. There’s a way out for him, but it means turning back on his dear friend Imran Khan. But Riaz won’t do that—it’s not good business.

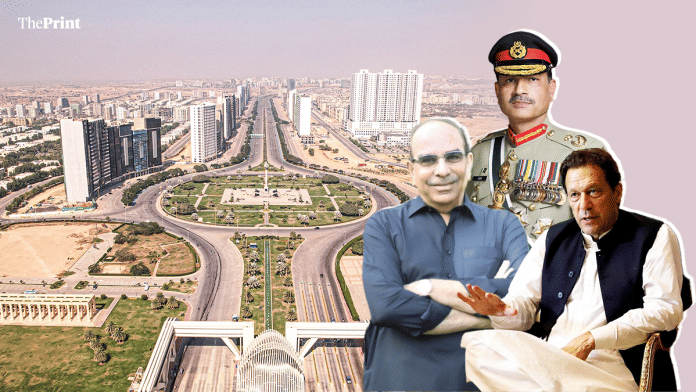

Pakistan’s biggest corruption case is a saga of friendships gone sour, military-ruled real estate, and a politician who tried to outwit the most powerful institution in the country. The Al-Qadir Trust case, also referred to as the £190 million National Crime Agency (NCA) scandal, involves former Pakistan prime minister Imran Khan, real estate mogul Riaz, and the Pakistan military. Six years later, Imran Khan is in jail, and the once “untouchable” Riaz is now essentially seeking a compromise with the establishment.

Insiders familiar with the case told ThePrint that Riaz’s rise was based on deep ties with both politicians and the military, which he enjoyed for years, until the big fallout—the military wanted him to turn approver against Imran Khan. But for a businessman like Riaz, becoming a witness would cripple his credibility.

Now, with the current military regime helmed by Field Marshal Asim Munir, who one person described as a “mad bully”, Riaz is looking for a settlement that won’t come through. Even President Asif Ali Zardari’s attempts have failed. For many, Riaz’s fall highlights how the saying rings true in Pakistan—“most countries have an army, but Pakistan’s army has a country”.

Pakistan navy vs army

In Pakistan, real estate is strict military business. Since the 1980s, the Defence Housing Authority (DHA), run by the military, has dominated the elite housing market in the country. Into this world stepped Riaz, a contractor who, by the late 1990s, had aligned himself with the Pakistan navy’s Bahria Foundation housing project. The Urdu word ‘Bahria’ has been used for the country’s navy.

In 1996, Riaz’s construction company Hussain Global made an agreement with the Bahria Foundation to start what is purportedly Asia’s largest private housing society, Bahria Town. According to this agreement, the Bahria Foundation was offered a 10 percent share just for allowing the use of the name ‘Bahria’ for the scheme which would create a gated community for the navy. The remaining earnings went to Hussain Global, Riaz and his family members.

Four years later, however, the foundation asked Riaz to stop using the name ‘Bahria’ for the society, once the agreement ended. They claimed that it was damaging the reputation of the armed forces.

Riaz agreed to not use it permanently, but his team requested to use it for 18 more months. However, in 2002, the Pakistan navy filed a case against him, after which Riaz got a stay order from a local court, claiming that the Bahria Foundation had forced him to sign the 1996 agreement, and continued expanding his housing project in Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Lahore and Karachi.

While the partnership collapsed, Riaz went fully private with the name ‘Bahria’, going from power to power, now that he had essentially won against the Navy.

Over the next decade, with an alliance of friendships with generals, he became the real estate mogul who built sprawling gated properties across major cities, like Rawalpindi, Lahore, and eventually Karachi, where his 60,000-acre or 24,000-hectare mega project effectively created a “parallel metropolis”. With its manicured lawns, golf courses and Dubai-style master planning, Bahria Town became the next big thing in the country.

To put it into perspective, a former government official requesting anonymity told ThePrint, “It basically created a whole alternate Karachi. If I had to compare with India, Karachi is almost as big as Bombay. Think of it—one day, a developer gets up in the morning, and builds a new Bombay there which gives much better facilities”. By the early 2010s, not only was Bahria Town competing with DHA, it was outpacing it in scale and public profile. That success carried risk.

For Pakistan’s military, which treats DHA as both a welfare scheme and a vast profit engine, the once favourite with the generals had now become a rival. For the first time, the military’s own housing projects had a competitor.

In March 2015, a civil court accepted Bahria Foundation’s request to stop Riaz from using the name ‘Bahria’ for his project. Then in 2018, a district court ruled in favor of Bahria Foundation and ordered Riaz to pay 388.13 million Pakistani Rupees (approximately 121 million Indian Rupees) in damages.

The court also imposed a fine of 15,000 PKR (over 4,000 INR) as court fees, to be given to Bahria Foundation. Originally, the foundation had demanded 688.83 million PKR (213 million INR), but the court decided on a lower amount. Interestingly, Barrister Gohar Ali Khan, who is now the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaaf chairman, had represented Riaz’s housing society in court in 2018.

Also Read: Asim Munir lands in China’s Tianjin, becomes first Pakistan army chief to attend SCO Summit

Bahria vs DHA

The project, launched around 2013–15, marked a turning point in Riaz’s fortunes. Until then, his modus operandi had been clear—cultivate ties with retired generals, gift them plots, bring them on board, and ensure the military elite had a stake in Bahria’s success. In Pakistan, this was simply how business was done. “Just as in India, politicians hold the keys, in Pakistan it is the generals who matter”—as a government insider put it.

DHA and Riaz together reportedly took control of land worth 62 billion PKR (19 billion INR), affecting around 150,000 low and middle-income people.

But Bahria Town Karachi upset this delicate balance. For decades, DHA Karachi had been the crown jewel of elite housing, providing a secure neighborhood where businessmen, politicians, and even underworld figures like Dawood Ibrahim once had homes.

The rivalry quickly soured into hostility. For the army, Bahria’s rise was no longer just about real estate, it was about “institutional dominance”, said one journalist, speaking to ThePrint about the case. The breaking point came with the Karachi land acquisitions in Malir, setting off a chain of legal and political battles that would ultimately pit Riaz against the most powerful institution in Pakistan.

The dispute came to a head when the country’s Supreme Court, allegedly under pressure from the military, as another insider put it, forced Bahria Town to settle at 475 billion PKR (148 billion INR) over cheap land deals by the government in Karachi’s Malir district. An investigation by Pakistan’s leading national daily Dawn showed that Bahria Town Karachi (BTK) was being developed over 23,300 acres (9,000 hectares) in Malir, Karachi’s green belt. In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that BTK had illegally acquired thousands of acres, declaring the acquisition “void ab initio”, and criticising the Sindh Board of Revenue and Malir Development Authority for their role.

While the court later allowed BTK to retain 16,896 acres (6,000 hectares), it strictly barred any further expansion, warning that violations would trigger criminal action against both government officials and Bahria’s management. Despite this, Dawn’s investigations suggested that BTK quietly expanded into Jamshoro district, adjacent to Malir.

DHA also accused Bahria of owing 1.4 trillion PKR (434 billion INR) to it in Rawalpindi-Islamabad land transactions.

What happened in UK

Even as the Karachi case unfolded, a parallel drama began in London. In 2019, Britain’s National Crime Agency (NCA) froze £190 million ($239 million) in assets linked to Riaz and his family on suspicion of money laundering.

UK law allowed for civil settlements without criminal charges if funds were returned. But instead of being routed into Pakistan’s treasury, then prime minister Imran Khan’s PTI government, advised by accountability chief Shahzad Akbar, allegedly approved an unusual plan—seized funds would be deposited directly into Supreme Court’s account, offsetting Bahria Town’s 460 billion PKR (143 billion INR) settlement.

Soon after, Bahria Town also donated land for a new educational institution, the Al-Qadir University Trust, founded by Imran Khan and his then wife, Bushra Bibi. Riaz was said to have good ties with Bushra Bibi.

For Pakistan’s National Accountability Bureau (NAB), this raised red flags. Investigators alleged it was a quid pro quo—Riaz’s UK-frozen funds were used to settle his debts, while the land grant benefitted Khan’s trust. NAB claims the arrangement deprived the state of more than $239 million (over 21 billion INR).

Imran Khan government-era officials dispute this framing. His accountability adviser Akbar told ThePrint that the UK funds were never meant for Pakistan’s treasury, that the Supreme Court’s account is a government-controlled channel, and the land went to a registered trust, not Khan personally.

“The NCA case was civil, not criminal; had it gone to trial, it could have dragged on for years with uncertain results. The settlement ensured the money returned to Pakistan, parked in the Supreme Court’s account. Between 2020 and 2022, the Court even earned billions in profit by investing those funds in savings accounts,” Akbar said.

For him, the real controversy began later, when political rivals and the military establishment turned the arrangement into a corruption case against Khan.

Army vs Imran Khan

By 2022, Imran Khan was ousted, and Pakistan’s new ruling coalition backed by the army allegedly weaponised the Al-Qadir Trust case. In early 2024, he was sentenced to 14 years in prison, while Riaz faced a sweeping crackdown.

For Imran Khan’s opponents, the case is simple—state funds were misused to help a politically connected tycoon. For his allies, it is a politically motivated narrative designed to sideline him permanently.

Even former Inter-Services Intelligence chief Faiz Hameed, who was once considered close to Imran Khan, was embroiled in the case. In May last year, former Pakistan federal minister Faisal Vawda accused Hameed of being the “architect, mastermind, and biggest beneficiary” of the Al-Qadir Trust case. Hameed was later court-martialled for his corruption allegations in another real estate scam—the first ISI chief in the history of Pakistan to ever be court-martialled. Both Hameed and Riaz were asked to turn approver against Khan, but refused.

Other cases against Khan, from disclosures of state gifts (Toshakhana case) to challenges over his marriage (Iddat case), have largely collapsed in court.

The Iddat case was filed against Imran Khan and wife, Bushra Bibi by the latter’s former husband Khawar Maneka, six years after their marriage, claiming that Khan had married her during her Iddat period of close to three months, which is a mandatory waiting period after a divorce in Islamic law. In 2024, both were acquitted.

But the Bahria Town saga has stuck. The reason, observers say, is simple—attach Imran Khan’s name to Riaz, and public opinion turns sharply. One insider said that Riaz once told him, “If you want to destroy someone in Pakistan, link them to Malik Riaz. The narrative alone will finish them.”

A journalist who worked on the Bahria case added, “The generals personally gained from him. But institutionally, once Bahria grew bigger than DHA, it had to be cut down.”

Behind the scenes, the pressure was intense. Family members were harassed, assets frozen, and even associates in the UK threatened. But both Imran Khan’s allies and Riaz himself refused to concede guilt or strike a deal, according to sources familiar with the case.

Akbar insists his only “crime” was refusing to testify against Khan: “There is not even an allegation that I took a bribe. My sin was challenging the army’s influence while in government, and later, refusing to become their witness.”

An offensive abroad

What particularly angered the establishment was Riaz’s decision to go on the offensive abroad. Instead of retreating, he launched BT Properties Dubai—a multibillion-dollar project in South Dubai that quickly sold out in its first phase. For many investors, Bahria Town remained a trusted brand. For Pakistan’s army, this was open defiance.

Now, the crackdown has only deepened under army chief Munir, whose tenure marks what critics describe as the “most overtly authoritarian phase in recent memory”. Munir, insiders say, sees no room for compromise. Where past chiefs operated with a mask of political accommodation, his approach is blunt—consolidate control, crush opposition, and keep the economy, especially land and real estate, firmly under military oversight.

At present, Riaz faces a stalemate. Pakistani authorities have frozen Bahria Town’s accounts, seized assets, and arrested staff, forcing a near shutdown. The NAB is also seeking his extradition from the UAE. The NAB Rawalpindi, earlier this month, auctioned three out of six commercial properties owned by Bahria Town as part of efforts to recover dues under a court-approved plea bargain.

According to former government officials, the auction was held to recover the outstanding amount agreed in the judicial settlement. Bahria Town’s Rubaish Marquee was sold for Rs 500 million. Conditional offers were also received for Corporate Office One and Corporate Office Two, with final approval still pending. The other three properties did not attract acceptable bids, and will be put up for auction again at a later date.

Another official in the know said that Riaz’s properties in London are being sold to a man close to Pakistan army, Masawar Abbasi, whose name was on Pakistan’s Fourth Schedule under the Anti-Terrorism Act in early 2019 over alleged links to land mafias and extremist groups. However, by October the same year, his name had been quietly removed, reportedly with the help of influential connections like Junaid Afridi, brother of then interior minister Shahryar Afridi. That timing had raised questions as it had coincided with the launch of his media network, fuelling speculation that the military had helped position him as a proxy.

“This is the new wave. Riaz’s properties are being auctioned, and right now his own brother has been in ISI custody for six weeks. Many of his people, ex-army brigadiers, generals, even Asim Munir’s own course mate, Colonel Khalil ur Rehman who was Bahria Town’s Vice executive, are in FIA (Federal Investigation Agency) custody. Moreover, instead of bowing down or agreeing to pay, Riaz launched a new mega project in Dubai. For the army, that was seen as an open insult—as if he was spitting in their face. And now, they’ve decided they won’t spare him,” a government official told ThePrint.

“It is a classic story of Military Inc. First, the faujis capture all the resources to erect an empire of $200 billion, and when any competitor rises, he is taken down. They use state machinery and power to take them down—NAB, FIA, FBR (Federal Board of Revenue), SBP (State Bank of Pakistan) , all pawns of the military-run empire. Our national anthem is ‘Yeh Watan tumara (fauj) hai, hum hain khawamakha is mein (this country is the army’s, we are in it for nothing)’.”

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: Serving major gen appointed to Interior Ministry as Pakistan army corners high-ranking civilian post