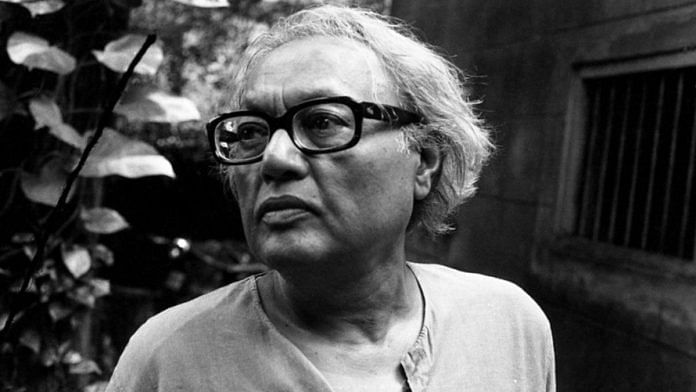

Armed with a pocket-sized notebook and an insatiable curiosity, Subrata Mitra trailed French director and screenwriter Jean Renoir’s set for The River in Kolkata. The 21-year-old science graduate had already been rejected to work as an assistant on the 1951 film but he continued to observe and document every nuance and shadow with meticulous sketches. His stubbornness paid off; not only was he noticed by the film’s cinematographer, Claude Renoir, but he also met his lifelong collaborator—Satyajit Ray. Mitra’s protege, filmmaker Dev Benegal, documents this encounter in an essay remembering the cinematographer.

Then, Ray was still an illustrator working at an ad agency. He had just acquired the rights to make his debut film Pather Panchali. After meeting Mitra in 1951 on Renoir’s set, Ray entrusted him with the cinematography of what is now regarded as a landmark movie in Indian film history.

The work of French street photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson enchanted them both. They wanted to bring his use of light and contrast to the silver screen.

It was in this pursuit that Mitra introduced ‘bounce lighting’. Used in Aparajito (1956), it was a technique unheard of in Indian cinema. By using a white cloth and studio lights, the cinematographer stimulated a “diffused daylight feel”. And inspiration struck him everywhere. Benegal writes how he used a plastic cup on an Indian Airlines flight to make a light meter.

From his meticulous attention to detail to groundbreaking techniques, Mitra’s legacy illuminates Indian cinema.

Also Read: Satyajit Ray: Cine maestro & literary genius who could say no to Indira Gandhi, Narasimha Rao

A wizard of light

Mitra, who had never held a motion picture camera before Pather Panchali, created a National Award-winning film with Ray. The film has been featured on multiple global top 100 movie lists.

Ray’s son and director Sandip Ray describes Mitra as ‘a man ahead of his time, a remarkable technician’.

“He would check every single print personally. These are the people we classify as geniuses. There is no better word to describe him,” he says.

The Ray-Mitra collaboration birthed a revolution in Indian cinema. They created masterpieces like Pather Panchali, Charulata (1964), and Devi (1960). Mitra’s lens wove emotions, as seen in the iconic freeze-frames at the end of Charulata—when the hands of the lead characters are reaching out to each other.

“It was because of him that in father’s films, it would feel like there was no artificial light at all. He was a wizard, a master. The camera was something he knew by heart. How else could a man create magic in his first film,” Sandip says.

Also Read: Shatranj Ke Khiladi to Sadgati — when Satyajit Ray found his inspiration in Premchand

Perfect cinematic eye

Journalist Ranjan Dasgupta describes Mitra as the “perfect cinematic eye of Satyajit Ray”. “So well did he understand Ray’s thoughts, imagination and visualisation that his camera interpretation of them was sans any flaws,” he writes.

In an essay, Ray wrote about “Subroto, my cameraman” who has “evolved, elaborated and perfected a system of diffused lighting whereby natural daylight can be simulated to a remarkable degree”

Their collaboration lasted 15 years until creative differences led to a dignified parting after 1966’s Nayak. Mitra’s departure left a hole in Ray’s films. An article in Outlook paying its ‘tribute to a master’, says that the post-Mitra era, though still poignant, “wore a more home-made look; their elegance more approachable”.

Mitra’s brilliance extended beyond Ray’s films. In 1963, he worked on his first Merchant-Ivory Productions’ The Householder. Over the decade, he collaborated with the production house on other films like Shakespeare Wallah and The Guru.

Mitra shot only in black and white until 1962’s Kanchenjunga. It showcased his refined experimentation with colour, despite the nascent state of colour processing in India. His work in New Delhi Times earned him his first and only National Award for Cinematography in 1986.

The same year the Government of India conferred Mitra with Padma Shri, the fourth-highest civilian award. In 1997, The Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute in Kolkata appointed Mitra as Professor Emeritus of Cinematography.

And while Mitra’s legacy lives on in his landmark films, his name has faded away since his death on 8 December 2001.

In the dimly lit corners of nostalgia, Mitra’s presence lingers but as Ashok Mehta, a National award-winning cinematographer, lamented, “We Indians do not celebrate our genius, that’s why we need a Richard Attenborough to present our Gandhi to the world. And, we do not appreciate technology as an art, that’s why Subrata Mitra’s retrospective is celebrated in Italy, not here”.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)