India’s first IVF baby was born less than three months after the world’s first ‘test tube’ infant came into the world in 1978. Bengali physician Subhash Mukhopadhyay, also known as Subhas Mukherjee, pioneered it. But nobody believed him.

In-vitro fertilisation is one of the most popular and successful fertility treatments in the world. Mukherjee is credited as the ‘creator’ of India’s very first test-tube baby, Kanupriya Agarwal, nicknamed ‘Durga’ on 3 October 1978 in Calcutta (now Kolkata). The feat was accomplished a mere 67 days after the birth of the world’s first IVF baby, Louise Brown, in Britain.

But he was only credited for his achievement after his death as he did not publish his research work in peer-reviewed journals. He was, instead, ostracised by the medical and scientific community and the state government after an “expert” panel rejected his work. The central government forbade him from travelling outside India for any scientific conferences or meets.

His achievements were recognised only after India’s second physician to succeed in IVF, Dr TC Anand Kumar, reviewed Mukherjee’s notes in 1986. Unfortunately, Mukherjee had already taken his own life on 19 June 1981, reportedly writing, “I can’t wait every day for a heart attack to kill me.”

The 1990 Bollywood film Ek Doctor Ki Maut is loosely based on his life.

Also Read: Girindrasekhar Bose—India’s first psychoanalyst was pen pals with Sigmund Freud

The journey to discovery

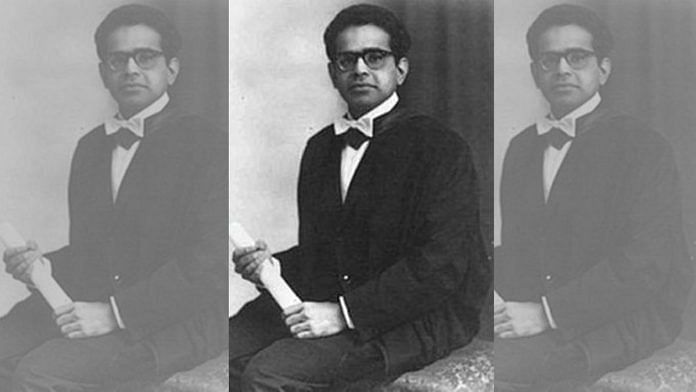

Mukherjee was born on 16 January 1931 in Hazaribagh in what is today Jharkhand. He graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in physiology from the University of Calcutta two years after Independence. Subsequently, he pursued an MBBS from Calcutta’s National Medical College in 1954 and earned a PhD in reproductive physiology from Rajabazar Science College in 1958.

A decade later he earned another PhD from the University of Edinburgh in reproductive endocrinology.

He joined as a professor at NRS Medical College in Calcutta in 1967, where he lived on campus. Mukherjee resided just one floor above an animal house he had built, where he kept rodents, rabbits, and monkeys for fertility experiments.

His research focused mainly on biochemical changes in pregnancies, and he was a pioneer in proposing reasons for complications decades before methodical research confirmed it. He had also worked on cholesterol and hormone relationships in ovaries when in Edinburgh, slowly developing a deep commitment to research in reproductive physiology and endocrinology.

He finally moved on to BS Medical College in Bankura, West Bengal, where he successfully created the first IVF baby.

Durga, whose parents wanted her to remain anonymous, was named to mark the day she was born—during the Durga Puja festival in West Bengal, at Calcutta’s Belleview Clinic.

Also Read: Bengal’s Ram Brahma Sanyal was Indian zoo pioneer in 1800s. Wrote handbook on care, breeding

Kept out of the limelight

The scientific community was not easily accepting of Mukherjee’s claims of a successful IVF implant and birth, as his techniques differed from the internationally-accepted methods established during the first IVF implant in England. Physiologist Robert G Edwards, gynaecologist Dr Patrick Steptoe and embryologist Jean Purdy, the team behind the first test-tube baby, had attempted to use the same method as Mukherjee but failed.

The process of IVF requires the release of an egg cell. Mukherjee used the human menopausal hormone gonadotropin to do this. The British team had also attempted to do this, but failed to preserve fertilised embryos as women progressed in their menstrual cycle; so they switched to trying with the natural cycle’s egg release. However, Mukherjee found out that if the embryos were frozen, he could use them for a woman’s next cycle. This technique of cryopreservation of embryos was scientifically reported five years after the birth of Durga.

Researchers, doctors and scientists did not believe his groundbreaking work was real when he presented it at various institutions in India. As the complete details of his work were not published in a scientific paper, he was mocked relentlessly and openly shunned by scientists, with the government following suit.

According to reports, an expert committee had been set up by the West Bengal government to evaluate his methodology, which refuted the authenticity of his work. The committee consisted of a radiophysicist, a neurologist, a gynaecologist, and a physiologist who had no experience in IVF research. He was immediately barred from travelling internationally for scientific events and to provide information about his work to anyone.

This embargo led to several innovative and novel techniques being buried under the sand – unearthed and recognised only years later.

After suffering a heart attack and being unable to cope with public ridicule, Mukherjee died by suicide in 1981.

Also Read: ‘Rothschild of Calcutta’, Mutty Lall Seal spent his wealth on education, health, uplifting women

Posthumous recognition

India’s first scientifically documented IVF baby, though it was the country’s actual second, was by TC Anand Kumar. Harsha Chawda Shah was born in Mumbai on 16 August 1986. The work was published in two scientific journals and received great recognition.

When Kumar was still regarded as the first physician to perform IVF in India, one of Mukherjee’s close friends and associates, food technologist Dr Sunit Mukherjee, asked him to review Subhas Mukherjee’s work and handwritten notes.

Upon reading the material, it was immediately clear to Kumar that Mukherjee had indeed performed the procedure successfully. It became evident that Durga’s family had requested he not publish details of the birth fearing their own ostracism in the community.

Kumar officially announced his findings, bringing recognition to Mukherjee’s work.

Kumar collected all of Mukherjee’s work and published them in the journal Current Science in 1997. Since then, his work has been cited and recognised globally.

Today, Mukherjee is widely celebrated for his seminal innovative technique of cryofreezing embryos and has the honour of having several labs across the country named after him.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)