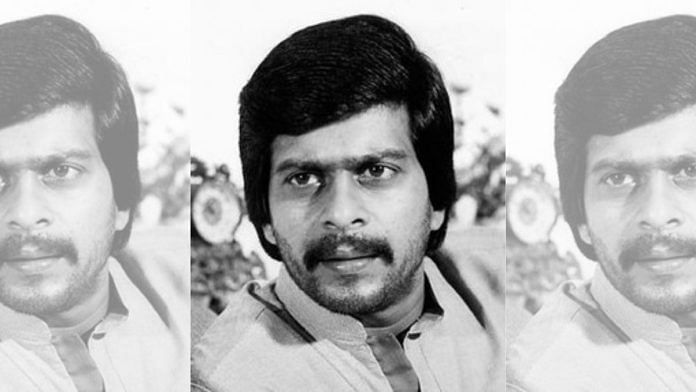

Bengaluru has changed from a city of lakes and retirement communities to a hub for startups and IT parks, but what’s remained constant is actor and director Shankar Nag. His legacy is woven into the fabric of the city. More than 30 years after his death, rickshaw drivers still display stickers of him on their three-wheelers—a way of honouring the actor who changed the way they thought of their profession, through his film Auto Raja (1982).

When director Sushma Veerappa made a documentary in 2013 on Bengaluru’s auto rickshaw drivers, she called it Shankar Nag Kelkond Bandaga (When Shankar Nag Comes Asking). She situated her work around a hypothetical question: How would the actor view Bengaluru today.

“Autorickshaw drivers still see Nag as ‘a rebel, saviour and their alter-ego’. The fact that he remains in public memory means he is a kind of superhero,” she said at the time.

He inspired an auto driver, Ramanna, to make a Kannada documentary film on his life. The world’s largest cinema hall equipped with Onyx Cinema LED screen in Bengaluru, Swagath Shankarnag Chitramandira is named after him. Kannada actor Naveen Shankar in a 2023 interview said that it was Nag who inspired him to add Shankar to his name.

“He was a beautiful flash of lightning, full of power, not the type that destroys what it lands on, but illuminates the path,” says his wife, actor and thespian, Arundhati Nag.

And across India, a generation of Indians remember him as a man who brought RK Narayan’s Malgudi Days to their homes. Directed by Nag, the series ran for 20 years. It was his brother, actor-turned-politician Anant Nag who convinced him to take up the job.

Also read: Child bride to doctor—Bengal’s Haimabati Sen traded her gold medals for a monthly stipend

Rise of ‘working class hero’

Nag acted in over 90 Kannada movies, in a career spanning 12 years from 1978 to 1990. He met his wife when he was studying in Mumbai.

“Shankar was very gentle. I’ve never seen him angry. That’s speaking a lot. As the woman, as his partner we really have never fought. Not once,” says Arundhati.

She recalls that Nag was actively involved with the Chhabildas Movement for experimental Marathi theatre, a space that came up as a reaction to the prevalent commercialisation of cinema and theatre. It was where he met Amol Palekar, Smita Patil and Girish Karnad. He assisted theatre director and screenwriter Sai Paranjpye in many of her early films, says Arundhati Nag.

He got his big break in Girish Karnad’s Ondanondu Kaladalli in 1979. In the Kannada-language adaption of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954), Nag plays a mercenary who finds himself embroiled in a power struggle between two warring brothers.

The movie became a cult classic in Karnataka, and earned him a national award at the Delhi International Film Festival. And he also earned the moniker, Karate King. American film critic Vincent Canby in his review of the film in The New York Times, wrote that Nag’s character “has a lot of the force and humour of the younger Toshiro Mifune [the Japanese actor who played a samurai in the original movie].”

Then came Auto Raja (1982) —where he played Raja, an autorickshaw driver which deals with inter-class love. Shankar Nag’s Raja made him a working-class hero, much like Dev Anand’s Mangal in Taxi Driver (1954).

His directorial debut Minchina Ota (1981) is also considered a masterpiece. It won seven state awards and a Filmfare Award for best director. Nag was the writer, director, producer and actor in the film.

In a book about his brother, Nanna Tamma Shankara, Anant Nag wrote about how much directing a film mattered to him.

He recalled the controversy around Accident (1985), a film that Shankar Nag had directed. It was about an influential politician’s attempts to save his son who had run over pavement dwellers. Anant Nag wrote about how a censor board refused to clear the movie’s climax of the hero killing the minister. The country was still raw over assassination of Indira Gandhi, at that time. Nag was unhappy about the change.

Ananth recalls how during the live telecast of Gandhi’s funeral, the moment he stood up, out of respect for her, Shankar screamed at him, asking him to sit down. For Shankar, politics did not override art and Ananth calls this moment Shankar’s first ‘political decision’.

The man who did it all

Nag always retained his love for theatre even when he was a movie star. With his wife, he created a group called Sanket Theatre in Bengaluru, which still produces many plays. It’s now the Sanket Trust and oversees activities at Ranga Shankara, a theatre that Arundhati Nag started in 2004. Today, it is one the more prominent theatre spaces in India.

For Arundhati, this is not something she ‘inherited’ from her husband, her partner in theatre. As thespians, they were both equal on stage. “It is our legacy that I uphold now. If I had died in the accident and Shankar would have lived, he would have built the theatre and since he is not there, we few friends, got together, and built it,” she says.

On the morning of 30 September 1990, Nag died in a car crash at Anagodu village on the outskirts of Davanagere in Karnataka. A lorry hit the car he was travelling in along with Arundhati and their daughter.

In his biography, Nag’s brother notes that on breaking the news of his death to his mother, she said, “He was supposed to die many years ago as a child in Mumbai when he almost got hit by the truck. The time he got until now since then was his gift. A second birth.”

For Arundhati, Shankar and his legacy lives on. “If Shankar is around anywhere, he’ll be proud of us,” she says.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)