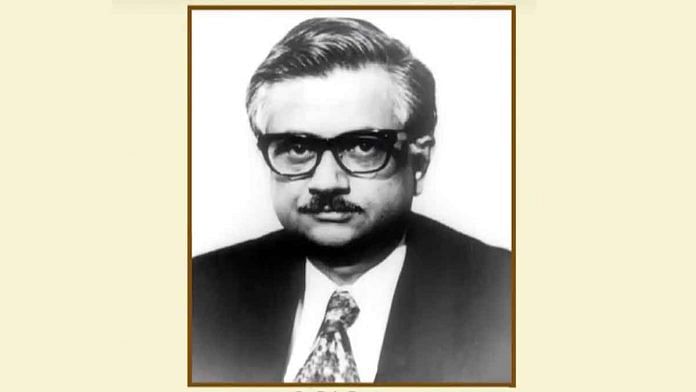

A birthday tribute to nuclear physicist Raja Ramanna, who played a crucial role in the early days of India’s advent as a nuclear power.

New Delhi: Nuclear physicist Raja Ramanna, then 53, was in Iraq as a guest of Saddam Hussein in 1978 when the latter reportedly left him stunned with a strange request.

Hussein wanted Ramanna to stay back in Iraq and take over the country’s fledgling nuclear programme.

This was four years after Ramanna had led India’s first nuclear test in Pokhran, an event that had got the world to sit up and take notice.

Hussein’s request scared Ramanna, who is said to have stayed up the whole night, wondering if he would ever be able to return home. He took the next flight back and was only then able to breathe easy.

This incident stands testament to Ramanna’s renown as a nuclear physicist, but the scientist, born 28 January 1925 in Tumkur, Karnataka, was a man of many more talents: An accomplished pianist who played concerts and a scholar of Sanskrit literature and philosophy.

On his 94th birth anniversary, ThePrint remembers Raja Ramanna, who played an important role in the crucial early days of India’s advent as a nuclear power.

A shared love of music

According to his profile on the Vigyan Prasar website, Ramanna wrote in his autobiography Years of Pilgrimage (1991) that his mother Rukminiamma was a voracious reader who was born into a wealthy family. Rukminiamma, he wrote, was the “first woman in Mysore to use electricity for domestic purposes”.

His father B. Ramanna, he said, “was in the judicial service of the Mysore state and earned the reputation of being a kind-hearted judge”.

Ramanna received his early education in Mysore and Bangalore, where he attended the Bishop Cotton School and St Joseph’s School. He subsequently joined the Madras Christian College, where he got a BSc in physics, before joining London University for his PhD.

His first meeting with Homi Jehangir Bhabha, the father of the Indian nuclear programme, happened in 1944, arranged by a mutual acquaintance who was aware of their shared love for Mozart.

Three years later, Bhabha offered Ramanna a job at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), the centre of India’s atomic energy programme. But it was another two years before Ramanna joined TIFR, as he was then in the midst of his PhD.

In 1949, he joined TIFR, from where he was transferred to the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), India’s primary institution for indigenous nuclear power and technology, in 1953 as the head of the nuclear physics division. BARC was then known as the Atomic Energy Establishment, Trombay, only earning its present name after Bhabha’s death in 1966.

Ramanna went on to become the director of BARC, where he headed the team that conducted India’s bomb detonation at Pokhran in 1974.

Talking about Pokhran, he told India Today in a 1983 interview that the blast changed India’s engagement with the world.

“We may have become suspect in the eyes of some vested interests in the world. I cannot do anything if countries suddenly decide to change their minds about giving us supplies. Even before the blast, all these restrictions had been talked of,” he said.

Asked if the explosion had set India’s nuclear programme back because of the criticism it elicited, Ramanna replied, “As for setting us back a decade, this is playing about with words. I could say instead of being pushed, the programme has been enhanced by five decades. It has lifted our backs.”

Ramanna is said to have had a good rapport with former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, during whose tenure the Pokhran test was conducted.

“When Mrs Gandhi returned to power in 1980, with a renewed interest in the nuclear weapons programme, Ramanna was in close contact with her,” The Guardian wrote in his obituary in 2004.

Also read: Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar, a petroleum luminary who fired up India’s science & tech pursuit

Keeping talent from flying away

Apart from his active role in furthering India’s nuclear programme, he also helped Bhabha organise training programmes at the Atomic Energy Establishment.

According to the website of the Department of Atomic Energy, his contribution to the training programmes is as significant as his role in nuclear weapons development.

He had an abiding interest in nurturing Indian talent — an interest fuelled by his fear of ‘brain drain’. “He felt that the training school churned out scientists for the future and also helped greatly to stall ‘the emigration syndrome’,” the website adds.

The profile on the website also features an interesting anecdote involving Ramanna and Dr P.S. Nagarajan, a student of the first batch of the training school.

“Dr Ramanna was scheduled to address the trainees,” the profile reads. “Nobody noticed when a young officer came, stood near the small table nearly reclining against it and started talking…One of the trainees approached the officer and told him that they were waiting for Dr. Ramanna. ‘I am Dr Ramanna’, he said. Nobody could believe that the person who looked like a college boy was indeed Dr. Ramanna,” it adds.

Beethoven, Mozart, Liszt

In Years of Pilgrimage, Ramanna reveals himself as a man of varied talents, including playing the piano. He wrote a book on music, The Structure of Music in Raga and Western Music, and frequently performed at concerts with Beethoven, Mozart and Liszt on his playlist.

In 1978, the nuclear physicist served as the scientific adviser to the defence minister and simultaneously held the post of director-general of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO). In 1988, he was invited by industrialist J.R.D. Tata to be the first director of the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore.

Two years later, he became minister of state for defence, briefly, under V.P. Singh.

Over the years, he was awarded three of India’s four most prominent civilian awards — Padma Shri, Padma Bhushan and Padma Vibhushan.

He died at the age of 79 years in Mumbai on 24 September 2004. He was survived by his wife, two daughters and a son.

Also read: German Ambassador to India is diplomat by day and concert musician by night