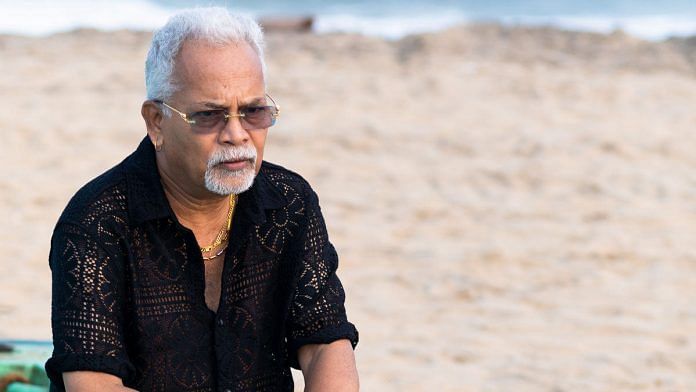

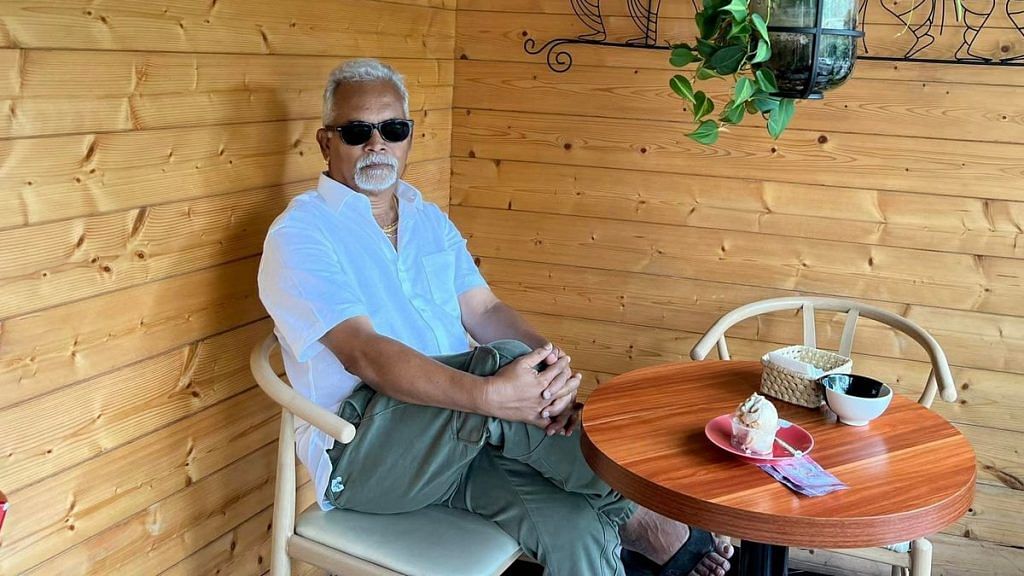

Pune: Charu Nivedita, born with another name, is a 70-year-old Tamil male writer who sports torn jeans and three gold necklaces.

The necklaces were gifted by three fans. A fourth fan pays the monthly rent of Rs 50,000 for the writer’s house in Chennai’s upmarket Mylapore. Another fan has sponsored his travels to different parts of the world.

A short, wiry man, Charu told me recently at the Kerala Literary Festival on Calicut beach, “In Tamil Nadu, I am a rock star.”

But, as he and some fans who followed him to Calicut acknowledged, the statement is not entirely true.

While Charu Nivedita does have a cult following, and the recent translation of his historical satire Conversations with Aurangzeb (2023) has garnered major literary attention across the country, his work hasn’t been universally embraced.

Described as “auto fiction”, “postmodern”, and “meta narrative”, his writing plunges into themes of unconventional sex and extreme violence, drawing comparisons to the French philosopher and writer Georges Bataille (1897-1962), who pioneered the “literature of transgression”.

But for those very reasons, Charu Nivedita’s work has also been despised. For decades, he was dismissed as a peddler of porn. “At many literary events, discussions of my work led to physical violence,” he recalled. Fearing for his life, he lived for five years under the pseudonym ‘Muniyandi’, the name of a rural Tamil deity.

What his critics did not probably realise was that all the sex and violence in his literature were reflections of the life he had experienced.

Also Read: ‘You can be a respectable Hindu and still an atheist,’ says author Gurcharan Das

‘Worse than untouchable’

Charu Nivedita was born into a poor family belonging to the Kattunayakan community, a Scheduled Tribe in Andhra Pradesh. Around 1945, the family migrated to Nagore, a coastal town in Tamil Nadu. “We were considered worse than untouchable,” he said. “Our women were said to be unchaste.”

The Nagore slum he grew up in had hordes of black pigs and no toilets. “Women relieved themselves behind bushes. Males like myself went to the cremation ground, fearing ghosts, snakes, and other venomous creatures.”

The loss of human dignity, the grip of superstition, and the acts of extreme violence that recur frequently in his fiction were all a daily part of his childhood.

Somehow “navigating through life”, he studied up to the pre-university level, obtaining a certificate after a two-year struggle.

Although he lacked the required qualifications, he got a job in Chennai as a clerk in the Tamil Nadu prison department. Inspired by the French writer Jean Genet (1910-86), who wrote about his past as a petty thief, Charu Nivedita considered writing stories about the criminals he met in the course of his work.

But he was soon transferred to another department, one he describes as “effectively a prison”. Seeking escape from that situation, he landed himself a clerical job in a government department in New Delhi.

This office, he recalled, was a den of corruption, so he routinely bunked work and went to a library where he read the works of French postmodern writers. “I absorbed their ideas and incorporated these into my burgeoning repertoire of stories,” he added.

While his stories were published in small Tamil magazines, no book publisher showed interest in his longer works due to their transgressive themes.

In 1988, he quit his job and moved to Chennai, where he started self-publishing his books, raising money by selling his wife Avanthika’s jewellery. However, the Tamil literati treated him as an “untouchable”, and the income from writing was paltry.

To make ends meet, he resorted to pickpocketing. That phase ended after one failed attempt in a crowded bus, and so he became a “catamite”—catering to the desires of older gay men. Then, he said, a woman entered his life and guided him to a “more conventional existence”.

Along the way, he became a Francophile, a connoisseur of Latin America cinema, an admirer of Arab and ancient Tamil literature, an expert cook, and a lover of strays.

Prodigious writer

Over the past 45 years, Charu Nivedita has written nearly a hundred small books on diverse topics such as world cinema, music, arts, and Arabic literature. His prolific output also includes seven novels, several short story collections, two plays, and a large number of newspaper and magazine articles.

However, major literary recognition eluded him until around two decades back. “There was a boom in the software industry, and a new generation of readers emerged. People started to take note of me,” he said.

While his Tamil readership remains modest, Charu has garnered “significant popularity” in Kerala through Malayalam translations of his works.

An English translation of his second novel, Zero Degree (1998), was published in 2008 and has been reprinted thrice. An excerpt from the novel appears in 50 Writers, 50 Books—The Best of Indian Fiction, published by HarperCollins (2013).

Conversations with Aurangzeb, his most recent work to appear in an English translation, has received rave reviews and has been discussed at many literary fests.

But it is an earlier autofictional work, Marginal Man (2018), the translation of a 2011 Tamil book, that gives a fuller picture of this extraordinary writer and his approach to writing.

Marginal Man

Marginal Man is ostensibly the story of a ‘Shudra’ Tamil writer named Udhaya, who grows up in the hovels of Nagore and Thanjavur.

Apart from recounting his own experiences, Udhaya tells the stories of two women he marries and several other people he comes to know: a lusty, married woman having an affair with him; a juvenile Dalit murderer; a compulsive fornicator; and a deranged recluse who thinks he has become a woman.

Running into nearly 700 pages, Marginal Man is divided into three parts, each with chapters of varying length. The longest chapter runs into 120 pages, the shortest comprises small paragraphs covering half a page.

A few chapters are written in a conventional narrative style, but most are in the form of vignettes interspersed with sociological or political commentary, references to Sangam works, and allusions to other writers and films.

The narrators switch—at one place, it’s a penis—and across the pages, the stories traverse time and space. In one paragraph, we are in Tamil Nadu, in the next we are in France, Malaysia or Singapore.

Sex forms a large part of the book, with vivid descriptions of encounters experienced by Udhaya and his male friends, the sexual thoughts of his woman friends, and details such as the varied ways in which female genitalia features in the Tamil lexicon of swear words.

This writing is graphic, even crude, and predictably, has drawn a lot of flak. But in the expanse and depth of the novel, the detailing of sex and violence, in all their ordinary and extraordinary forms, is necessary.

For this is a work about what seethes beneath the surface of daily life in the small towns and metropolises of India, especially Tamil Nadu.

The story of Udhaya is only one of several stories told in the book, and even that is not completely told. Rejecting the conventionally accorded central role of the author in the creation of fiction, Marginal Man gives space to several other voices who do not typically appear in mainstream writing.

Unique voice

Like his protagonist, Charu Nivedita was also once a ‘marginal’ person. But through his voice, he found a place in the literary world.

This voice is complexly constituted. As in the writer’s other works, the registers used in Marginal Man shift continuously, from Wikipedia-style text to lyrical passages; poetry to prose; tender and moving evocations to crass jokes; the scholarly to the burlesque.

Following the French writer Georges Perec (1936-82), who wrote the novel, La Disparition, without using ‘e’, the most frequently used letter in French, Charu composed his novel in Tamil without the use of ‘oru’ (‘a’, ‘an’ or ‘the’). This ‘lipogrammatic’ choice, which goes back to ancient Greek literature, is not reflected in the English translation.

However, the writer’s other innovative uses of language have been retained in the translation—such as entire paras composed of only one word, like the orgasmic “oghad” written over 200 times. Similarly, sprinklings of Tamil citations, French poetry, and sentences in large, bold lettering, akin to the intertitles in Jean Luc Godard films, carry over.

Also Read: ‘We write every word’—Daisy Rockwell busts illusion that translators don’t taint literary work

‘Wondrous journey’

How does one judge a work as unconventional as Marginal Man? In a WhatsApp conversation, Charu Nivedita agreed on three basic criteria—authenticity of voice, the acuity of a vision that challenges established representations, and craftsmanship.

On the last count, Charu admitted, Marginal Man flags. Six people, including himself, worked on the translation, but the outcome of their brave effort to reproduce the novel’s multiple registers is patchy. Also, he said, the sprawling novel required a “good editor”.

Published by a group of Charu’s friends in Chennai, Marginal Man is a demanding book. But those who read it till the end will experience what the Malayalam writer Paul Zacharia called a “wondrous journey”.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)