One evening, legendary composer Naushad Ali sat at his harmonium, immersed in his music, when a stranger barged into his home, tossed a bundle of cash onto the instrument, and declared: “You will compose the music for my film, Mughal-e-Azam.”

Startled and insulted, Ali picked up the money and flung it off his terrace. Notes fluttered down like autumn leaves, leaving bewildered house staff scrambling to gather them. The audacious visitor was none other than film director K Asif. At the time, the early 1950s, he was an unknown entity in Indian cinema. But his vision for Mughal-e-Azam (1960) knew no boundaries—of time, patience, or obsession.

Naushad eventually came around and what followed was a creative alliance that would shape one of Indian cinema’s greatest musical scores.

“This one man’s virtue was that he dreamt a beautiful dream, and he brought that very dream to life in the real world exactly as he had envisioned it,” said Rajkumar Keswani, author of the book Dastan-e-Mughal-e-Azam, in an earlier interview with ThePrint. “This one man gave millions of people the courage and determination to turn their dreams into reality.”

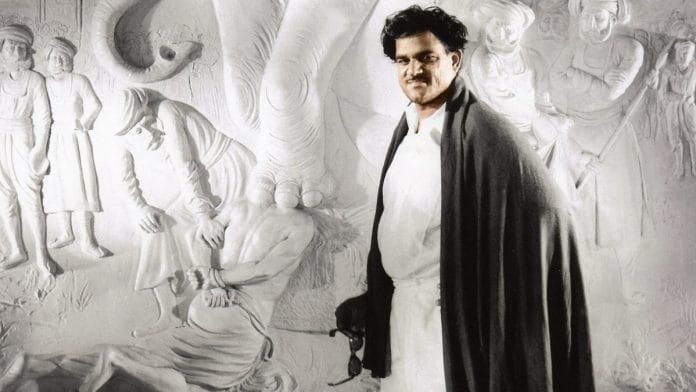

From his audacious recruitment of Naushad to his insistence on real pearls and painstaking attention to historical accuracy, Asif never compromised on his vision. Financial setbacks, actor replacements, and production delays plagued the film at every turn, yet he remained steadfast, sculpting what would become Indian cinema’s most celebrated epic.

He died on 9 March 1971, before completing his final project, Love and God, which was only released posthumously in 1986. Only three of his films saw the light of day, but that was all it took to make him a legend.

“People often credit Waqt as Bollywood’s first multi-starrer, but Asif had already done it in 1945 with Phool. He brought together an ensemble cast of huge names like Prithviraj Kapoor, Suraiya, and Durga Khote at a time when such a thing was rare,” said filmmaker Karan Bali. In Phool, Prithviraj Kapoor played the patriarch of a Muslim family who had to fulfil his father’s dream of building a mosque.

Most directors with such a short reel would have faded into obscurity. But Mughal-e-Azam ensured K Asif’s name would never be forgotten.

Also Read: Why Dilip Kumar initially said ‘no’ to Mughal-e-Azam

From a tailor to a titan

Born in Etawah, Uttar Pradesh, Asif arrived in Bombay at 17 with dreams as grand as the Mughal empire itself. His uncle initially set up a tailoring stall for him, but Asif was more interested in charming his female customers than stitching clothes. Seeing where his true passion lay, his uncle nudged him toward filmmaking. By his early 20s, he was a full-fledged director.

His first venture, Phool, was a box-office hit, but Asif was already fixated on something much bigger—the story of Emperor Akbar, his son Salim, and the doomed love of Anarkali.

“His films weren’t just made; they were sculpted,” said Bali, on the making of Mughal-e-Azam. Every rupee he raised was used to make the epic as grand and as authentic as possible.

“Whether it was importing glass from Belgium for Sheesh Mahal, commissioning special footwear from Agra, or having Dilip Kumar’s wig made in England—no expense was spared,” he added.

Mughal-e-Azam wasn’t just a movie for Asif. It was an all-consuming pursuit of cinematic excellence. It devoured over a decade of his life, drained vast fortunes, and pushed him to the brink of ruin. Yet, he never wavered. The film’s final budget is debated, with estimates ranging from Rs 10.5 million to Rs 15 million, making it the most expensive Indian film of its time.

He demanded nothing less than perfection, often clashing with financiers, actors, and technicians, testing their patience with his meticulous vision. He halted shooting for months just to acquire authentic period costumes, insisted on elaborate set designs, and reshot entire sequences if they didn’t meet his exacting standards, according to Anitaa Padhye in her 2020 book, Ten Classics.

At one point, his financier threatened to pull the plug. But Asif was a gambler, a dreamer, and an artist who bet everything on one film.

In a 2024 interview, veteran actor Prem Chopra recalled Asif as the kind of director who would sell his “last shirt” to complete a film. “He was an absolute fakir… but he made an evergreen film,” he said.

Also Read: Ameen Sayani was the town crier for millions. He took Bollywood music to rural India

The perfectionist

Asif insisted on using real pearls in a scene where Salim returns from war, delaying production for months until they were procured. Compromise was not an option. During the filming of a battle sequence in Jaipur, he noticed electric poles in the background—an anachronism in Akbar’s era. Instead of adjusting the camera angle, he halted production, left Jaipur, and spent three months persuading municipal authorities to remove the poles before resuming the shoot.

“Even when legendary filmmakers like David Lean and Roberto Rossellini visited the Sheesh Mahal set and claimed that filming there was impossible—because the mirrors would reflect the camera—Asif didn’t back down. Instead, he and his cinematographer, RD Mathur, took it as a challenge and devised a way to shoot without reflections ruining the shots,” Bali told ThePrint.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, the legendary Hindustani classical singer, was initially reluctant to sing for films. But Asif was determined to have his voice in Mughal-e-Azam’s musical sequences. At the time, playback singers earned a few hundred rupees per song, so Bade Ghulam Ali Khan quoted an unprecedented Rs 25,000, possibly assuming Asif would refuse. To his surprise, Asif readily agreed. The result was two unforgettable songs rendered by Bade Ghulam Ali Khan—Prem Jogan Ban Ke and Shubh Din Aayo.

Despite countless setbacks, Asif refused to abandon Mughal-e-Azam. The film, which began in the 1940s, nearly collapsed when its original Akbar, Chandramohan, died and financier Siraj Ali Hakim migrated to Pakistan. Undeterred, Asif spent years securing new backing, eventually convincing businessman Shapoorji Pallonji Mistry to fund the project. After 15 years of recastings and financial hurdles, Mughal-e-Azam was finally released in 1960.

His next project, Love and God, based on the Persian love story of Laila-Majnu, was equally grand but met with tragedy. Guru Dutt, cast as the lead, died midway through production and was replaced with Sanjeev Kumar. But before the film could be completed, Asif died in 1971 at just 48. Years later, KC Bokadia attempted to finish it with Rajesh Khanna, but when Love and God finally released in 1986, it failed at the box office.

“For Asif, cinema wasn’t about budgets or deadlines—it was about creating something timeless,” Bali said. “His only goal was to make films that would be remembered for generations. And in that, he succeeded.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)