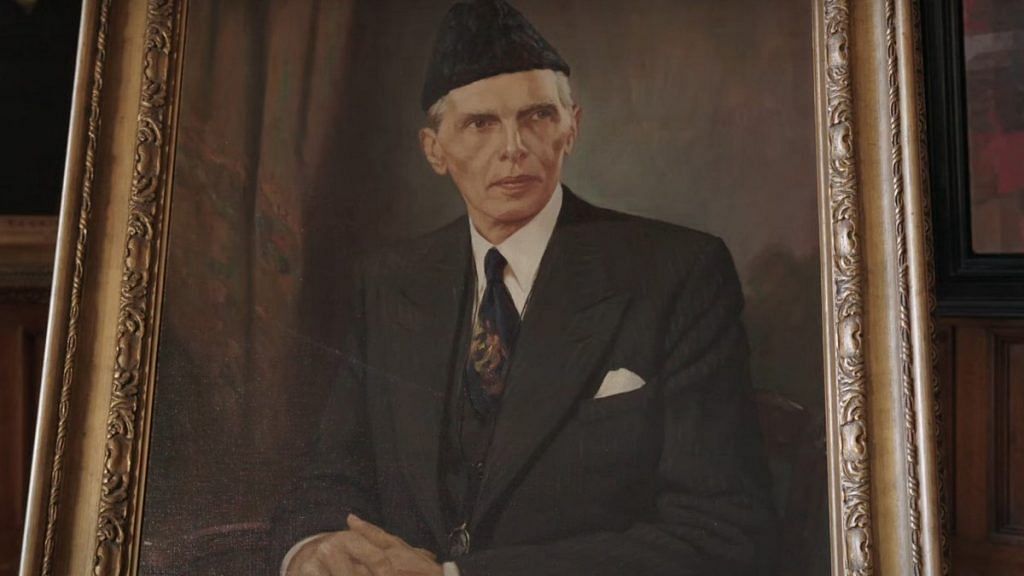

An oil painting of Pakistan’s founder Muhammed Ali Jinnah hangs at Lincoln’s Inn, the prestigious society of barristers in London. Dressed in a suit and tie, with a karakul hat perched on his head, Jinnah’s portrait gazes sternly into the distance. Among the portraits of English luminaries on the walls, his stands out as the sole non-white face.

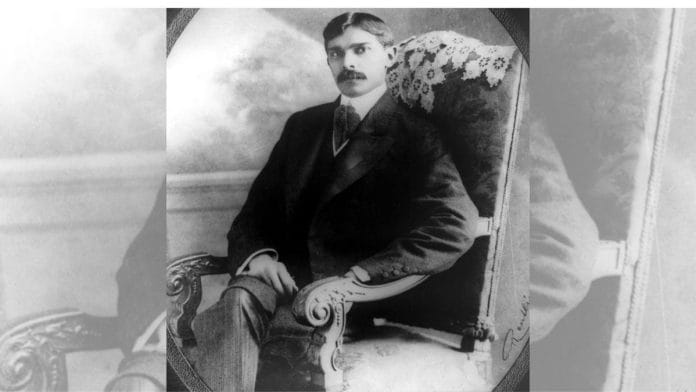

Little is known about a 16-year-old Jinnah’s first stint in England, where he enrolled at Lincoln’s Inn to study law. Initially sent to learn about the shipping trade, which his father— Jinnahbhai Poonja—was engaged in, Jinnah instead veered toward law and politics.

London left a deep imprint on him, though his early days were far from smooth.

“He [Jinnah] felt greatly alone in this strange land, was troubled by the cold climate, was uncomfortable in the midst of all those aliens and was not until then fluent enough in English language,” wrote former external affairs minister Jaswant Singh in his book Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence.

His departure to England in 1892 came on the back of two pivotal moments in his life. Marriage and his father’s financial misfortunes.

In May of that year, a court judgment stripped the family of its property. Unable to pay the decreed amount, Jinnah’s father decided it was best to send his teenage son to England before further damage was done to the family’s honour. Shortly after Jinnah left, Jinnahbhai declared insolvency, sold the family’s remaining property, and moved the household from Karachi to Bombay.

But marriage came first. Jinnah’s mother Mithibai, fearing he would end up marrying an Englishwoman and ruin the family name, arranged for him to marry 14-year-old Emibai, a distant relative from their ancestral village of Paneli. To fulfil his mother’s wishes and secure permission to travel to England, Jinnah acquiesced to the marriage without ever having met Emibai.

While in Karachi, Jinnah insisted that his wife shouldn’t cover her face in front of his father, dismissing the practice as archaic.

“There was something extremely modern, rebellious and non-conformist about Jinnah right from the beginning. This side of him was honed more when he travelled to London,” wrote Yasser Latif Hamdani in Jinnah: A Life.

By the time he returned to India at the age of 20 in 1896, both his wife and mother had died. His next marriage would come after a gap of 26 years, at the age of 42. He also decided to start building a career from scratch in Bombay rather than accede to his father’s request for him to work as a junior in the office of a prosperous advocate in Karachi.

“He had made up his mind,” wrote his sister Fatima Jinnah in My Brother. “He would go his own way; as usual, he wanted to learn the hard way—by kicks and hard knocks in life.” He’d already weathered several in London.

Also Read: Is Jinnah edging Mujib out in new Bangladesh? Hasina’s ouster reopens old histories

Life in London

The young Jinnah, by his sister’s account, was more interested in horses that studies. Hoping to set him on a “practical” path, his father got him an apprenticeship with an English friend, the general manager of a shipping company. But this was not to last.

Within a couple of months of arriving in England, Jinnah left Douglas Graham and Company, the shipping firm where he was apprenticing. Exposed to new ideas, however, new ambitions started to grow.

“He began to study and discuss about the lives of the great contemporary and past leaders of English public life. He discovered that many of them had studied for the Bar, and that a sound knowledge of law had stood them in good stead in their public life,” Fatima Jinnah wrote. The allure of the legal profession was too strong to ignore and Jinnah took a leap.

At the time, becoming a barrister did not require a degree. Admission to one of London’s four Inns of Court—Lincoln’s Inn, Gray’s Inn, Middle Temple, or Inner Temple—was the key to practicing law. Jinnah chose Lincoln’s Inn and began preparing for the entrance exam, the “Little Go,” which had three papers: English language, English history, and Latin.

Already displaying a penchant for putting forth strong arguments, Jinnah managed to gain exemption from the Latin portion of the exam.

In a petition to the bar council, Jinnah wrote: “Having spent my time in learning other languages which are required there [in India] I have not been able to learn the Latin language.”

He also claimed proficiency in several other Indian languages, considered “classics or second languages”. By most accounts, however, Jinnah was fluent in English and Gujarati, but only had rudimentary Urdu.

On 5 June 1893, Lincoln’s Inn admitted Jinnah, initially recording his age as 19 at the time of admission and 21 by the time he was called to the bar, according to archival records. However, Jinnah’s official birthday is 25 December 1876, which means he was just 16 when he enrolled and 19 when he passed the bar exam, making him the youngest person to achieve this distinction.

London marked the beginning of Jinnah’s romance with western civilisation and English culture.

“His eating habits changed. He preferred the bland English food over the greasy curried one that he had long been accustomed to,” wrote Yasser Latif Hamdani.

For his call to the bar, Jinnah even petitioned for his name to be changed, another step toward building a more modern identity.

“Sir, I beg to inform you that I am desirous of dropping the ending of my name, namely bhai – meaning Mr. Jinnah or in full Muhammed Ali Jinnah,” he wrote in a letter to the council.

Jinnah cultivated a cosmopolitan image, including a makeover of his personal style.

“He also traded in his traditional Sindhi long yellow coat for smartly tailored Saville Row suits and heavily-starched detachable-collared shirts,” wrote historian Stanley Wolpert in his book Jinnah of Pakistan.

A lot of the imagery associated with Jinnah—a tall, impeccably dressed, well-read, and charismatic politician—can be traced back to his time in London.

His lifelong habit of reading the morning newspaper from cover to cover was also born in England, where he had newspapers from across the world delivered to his doorstep. He would later start Dawn, Pakistan’s leading English language paper in 1941.

Jinnah’s love for Shakespeare, which he carried late into his life, was also formed in London when he frequented the Globe Theatre. After being called to the bar, he even auditioned for a Shakespearean theatrical company and landed a job offer.

His father, however, drew a line here and wrote Jinnah a letter, pleading with him to “not be a traitor to the family”. While that was the end of his stage career, Jinnah’s fondness for the limelight never quite left him.

Also Read: Why did Jinnah fade out of Congress? Gandhi reduced him to just a ‘Muslim’

Campaigning for Dadabhai Naoroji

The rise of British liberalism in the 1890s coincided with Jinnah’s transformative years in London. It was a time of political awakening, shaped by the ascent of leaders such as William Gladstone, who was elected as prime minister for a third time in 1892, and Dadabhai Naoroji, the first British Indian to enter the House of Commons as a Liberal Party MP.

“Jinnah attended sessions of Parliament and campaigned for Dadabhai Naoroji. These were clearly influences that he carried with him back to India,” Ayesha Jalal, a professor of history at Tufts University, told ThePrint.

The influence of Naoroji on a young Jinnah cannot be understated. Naoroji’s “drain theory” which argued that the British were siphoning India’s wealth, resonated with many Indians in England, including Jinnah.

The young barrister was appalled when outgoing Tory prime minister Lord Salisbury dismissed Naoroji as a “black man”.

“If Dadabhai was black, I was darker. And if this was the mentality of the British politicians, then we would never get a fair deal from them,” wrote Jinnah in a letter to his sister, as recorded in Stanley Wolpert’s biography.

Jinnah returned to Bombay in 1896, where he would first practice law and later enter politics as a liberal nationalist, joining the Indian National Congress.

Initially seen as a champion of Hindu-Muslim unity, Jinnah envisioned an India where both communities could coexist.

This is best exemplified through his role as an arbitrator between the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League (AIML). In 1916, Jinnah was instrumental in getting both parties to sign the Lucknow Pact, which pushed for constitutional reforms and self-rule from the British.

Breaking point

The cracks in this idealism soon began to show. Jinnah grew increasingly frustrated with what he saw as the Congress’ marginalisation of Muslim voices and its failure to address the concerns of minority communities.

The breaking point came after the 1937 elections, when the Congress refused to share power with the Muslim League in the United Provinces government.

“At that time there was no pride in me, and I used to beg from the Congress,” he said in a 1938 speech to the Aligarh Muslim University Students Union. “I worked so incessantly to bring about rapprochement that a newspaper remarked that Mr. Jinnah is never tired of Hindu-Muslim unity.”

He then made it clear he had changed his mind: “In the face of danger the Hindu sentiment, the Hindu mind, the Hindu attitude led me to the conclusion that there was no hope of unity.”

The liberal barrister and one-time aspiring actor who once campaigned for coexistence had started taking on what would be his final role—as Pakistan’s Quaid-e-Azam.

There is still debate about Jinnah’s motives—whether he used Partition as a bargaining tool for the Muslim League in a united India or truly wanted two separate nations. However, his call for Direct Action Day in 1946, demanding a Muslim homeland, led to violent communal riots that killed thousands and deepened the divisions leading to Partition.

Jinnah also left his contemporaries deeply divided. Lord Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India, dismissed him as a “psychopathic case”, yet MK Gandhi, despite their rift, said, “I am convinced Mr Jinnah is a good man.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

What is revolting is that Jinnah enjoys unmatched popularity in 21st century India. The list of his fanboys reads like a Who’s Who of Indian politics – Akhilesh Yadav, Tejaswi Yadav, Derek O’Brien, Mamata Banerjee, Mani Shankar Aiyar, Digvijaya Singh, etc.

The Left-liberal ecosystem in India, assisted by the Leftist- Islamist cabal in Western academia, has very effectively re-written modern Indian history in such a way that the blame for the partition of India has been placed on the shoulders of Savarkar, Golwalkar, Moonje, S Mukherjee and others from the Hindu right-wing political leadership. At the same time absolving Jinnah, Liaquat Ali, the Ali brothers, Suhrawardy and others from the Muslim League of any responsibility for the same.

History has been turned on it’s head – upside down.

The Hindus have been blamed while the Muslims were exonerated.