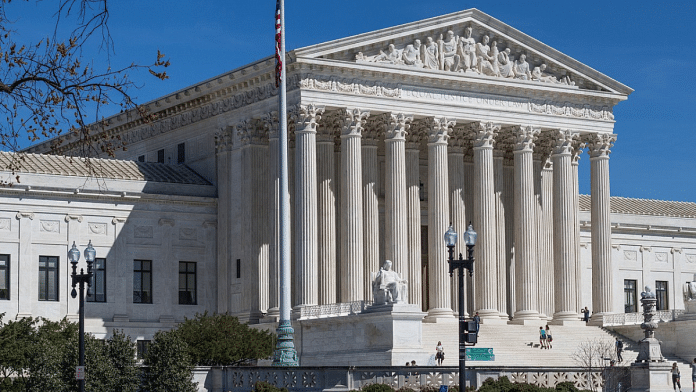

New Delhi: While the majority opinion by the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) struck down affirmative action in college admissions, the minority opinion decried “let-them-eat-cake obliviousness” and asserted that “deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life”.

On Thursday, the SCOTUS ruled that race can no longer be considered a factor in college and university admissions, and in effect, ended race-conscious admission programmes at colleges and universities across the country.

Affirmative action is a policy that aims to increase the representation of historically disadvantaged groups in education, employment and other areas. In the US, affirmative action has been used to benefit several such groups, including racial and ethnic minorities, women, veterans and people with disabilities.

“Many universities have for too long wrongly concluded that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned, but the colour of their skin. This nation’s constitutional history does not tolerate that choice,” the majority opinion said.

The question posed before the court was whether the admissions systems used by Harvard College and University of North Carolina (UNC) are lawful under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. It held that Harvard’s and UNC’s admissions programmes violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The majority opinion was delivered by Chief Justice John Roberts, and he was joined by his five fellow conservative peers — Justice Samuel Alito, Justice Clarence Thomas, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Justice Neil Gorsuch.

The three liberal justices on the bench — Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson — dissented in the UNC case, in which Justices Sotomayor and Jackson wrote separate dissenting opinions.

Justice Jackson, who was previously a member of the Harvard University’s Board of Overseers, recused herself in the Harvard University companion case.

However, the court added that nothing prohibits universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected the applicant’s life, so long as that discussion is concretely tied to a quality of character, or unique ability that the particular applicant can contribute to the university.

The court was petitioned by Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), a non-profit organisation whose stated purpose, as quoted in the judgment, is “to defend human and civil rights secured by law, including the right of individuals to equal protection under the law.” It had raised concerns over “Harvard’s mistreatment of Asian-American applicants” and said that “Harvard is obsessed with race”.

How do admissions currently take place at Harvard College and the University of North Carolina? What does the Equal Protection Clause say and why did the majority opinion feel that the clause was violated by the two colleges? What did the dissent say? ThePrint explains.

Also Read: US ending affirmative action for college admission is alarm for India. Rehaul reservation

How do admissions happen

The judgment noted that Harvard College and the UNC are two of the oldest institutions of higher learning in the United States, and every year, thousands of students apply to each school. Both the institutes employ a highly selective admissions process to make their decisions, it added.

“Admission to each school can depend on a student’s grades, recommendation letters, or extracurricular involvement. It can also depend on their race,” it said.

At Harvard, each application for admission is initially screened by a “first reader,” who assigns a numerical score in each of six categories — academic, extracurricular, athletic, school support, personal, and overall. For the “overall” category, a first reader can and does consider the applicant’s race.

Harvard’s admissions’ sub-committees then review all applications from a particular geographic area. These regional sub-committees make recommendations to the full admissions committee, and they take an applicant’s race into account.

When the 40-member full admissions committee begins its deliberations, it discusses the relative breakdown of applicants by race.

At UNC, every application is initially reviewed by one of approximately 40 admissions office readers, each of whom reviews roughly five applications per hour, the judgment said.

The readers are required to consider “(r)ace and ethnicity . . . as one factor” in their review, according to the judgment. Other factors include academic performance and rigour, standardised testing results, extracurricular involvement, essay quality, personal factors, and students’ background.

After assessing an applicant’s materials along these lines, the reader “formulates an opinion about whether the student should be offered admission” and then “writes a comment defending his or her recommended decision,” the judgment explained.

Following the first read process, applications then go through “school group review”, where a committee composed of experienced staff members reviews every initial decision.

The review committee either approves or rejects each admission recommendation made by the first reader, after which the admissions decisions are finalised. In making those decisions, the review committee may also consider the applicant’s race.

What does the law say

The SFFA filed separate lawsuits against Harvard and UNC. The question before the court was whether the race-based admissions programmes violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Before the court, SFFA argument focussed on Harvard’s purported discrimination against Asian-Americans.

It claimed that in some parts of the country, Asian-American applicants must score higher than all other racial groups, including Whites, to be recruited by Harvard. It alleged that Harvard admits Asian-Americans at lower rates than Whites, even though Asian-Americans receive higher academic scores, extracurricular scores, and alumni-interview scores.

The Fourteenth Amendment provides that no State shall “deny to any person . . . the equal protection of the laws”.

In the past, the US Supreme Court has explained that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed “that the law in the States shall be the same for the Black as for the White; that all persons, whether coloured or White, shall stand equal before the laws of the States.”

It looked at precedents to point out that the court has permitted race-based college admissions only within the confines of three narrow restrictions — such admissions programmes must comply with strict scrutiny, may never use race as a stereotype or negative, and must, at some point, end.

The strict scrutiny test mentioned among the restrictions has two steps — it checks whether the racial classification is used to “further compelling governmental interests”, and it asks whether the government’s use of race is “narrowly tailored,” that is, “necessary,” to achieve that interest.

‘Goals not sufficiently coherent’

Referring to the aforementioned three restrictions on race-based college admissions, the Supreme Court’s majority opinion said that the “respondents’ admissions systems fail each of these criteria and must, therefore, be invalidated under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment”.

The court felt that the interests that the universities view as compelling “cannot be subjected to meaningful judicial review”. These interests include training future leaders, acquiring new knowledge based on diverse outlooks, promoting a robust marketplace of ideas, and preparing engaged and productive citizens.

The court felt that, while these are commendable goals, they are not “sufficiently coherent” for application of the strict scrutiny test. “It is unclear how courts are supposed to measure any of these goals, or if they could, to know when they have been reached so that racial preferences can end.”

It added that, to achieve educational benefits of diversity, the universities measure the racial composition of their classes using racial categories that are “plainly overbroad (expressing, for example, no concern whether South Asian or East Asian students are adequately represented as “Asian”); arbitrary or undefined (the use of the category “Hispanic”); or underinclusive (no category at all for Middle Eastern students).”

It, therefore, felt that the universities fail to articulate a “meaningful connection” between the means they employ and the goals they pursue with those means.

Also Read: ‘Damaged your reputation’ — Over 500 academics write to IISc after it cancels talk on UAPA

‘Lacks logical end point’

The court also felt that the admissions programmes also lack a “logical end point” that precedents require. The universities had submitted that the end of race-based admissions programmes will occur once meaningful representation and diversity are achieved on college campuses, and when students receive the educational benefits of diversity.

Harvard had also submitted statistics to show the share of students admitted by race.

It submitted that each full committee meeting begins with a discussion of “how the breakdown of the class compares to the prior year in terms of racial identities”.

“If at some point in the admissions process it appears that a group is notably underrepresented or has suffered a dramatic drop off relative to the prior year, the admissions committee may decide to give additional attention to applications from students within that group,”

However, the court rejected these submissions, observing that “it is unclear how a court is supposed to determine if or when such goals would be adequately met”.

‘Let-them-eat-cake obliviousness’

In her dissenting opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor asserted that with its decision, the court “rolls back decades of precedent and momentous progress”.

“In so holding, the Court cements a superficial rule of colour blindness as a constitutional principle in an endemically segregated society where race has always mattered and continues to matter.”

She asserted that for more than four decades, it has been this court’s settled law that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment authorises a limited use of race in college admissions for the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body.

She felt that the majority judges’ interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment “is grounded in the illusion that racial inequality was a problem of a different generation”.

“Ignoring race will not equalise a society that is racially unequal. What was true in the 1860s, and again in 1954, is true today: Equality requires acknowledgment of inequality,” she observed.

She asserted that after more than a century of government policies enforcing racial segregation by law, society remains highly segregated. Her opinion also looked at how “both UNC and Harvard have sordid legacies of racial exclusion”.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, the top court’s first Black woman judge, also wrote a separate dissenting opinion.

“With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness, today, the majority pulls the ripcord and announces ‘colorblindness for all’ by legal fiat. But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life,” she said.

She called out the majority for their “ostrich-like” approach, and added, “The best that can be said of the majority’s perspective is that it proceeds (ostrich-like) from the hope that preventing consideration of race will end racism. But if that is its motivation, the majority proceeds in vain. If the colleges of this country are required to ignore a thing that matters, it will not just go away. It will take longer for racism to leave us.”

(Edited by Richa Mishra)

Also Read: Caste census is important — whether you are for or against reservation