New Delhi: In a judgement that could impact minority-run educational institutes in India, the Supreme Court Thursday struck down the Khalsa University (Repeal) Act, 2017, as “unconstitutional”.

Setting aside an order passed by the Punjab and Haryana High Court, a bench of Justices B.R. Gavai and K.V. Viswanathan ruled that the 2017 Act, “which was enacted with a purpose which was non-existent, would fall under the ambit of manifest arbitrariness and would therefore be violative of Article 14 (right to equality) of the Constitution”.

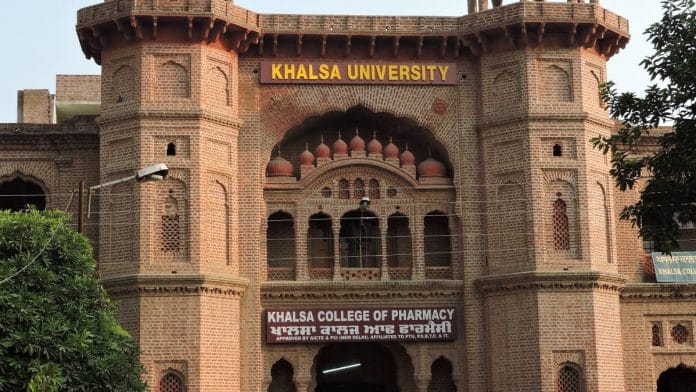

The 2017 Act repealed the Khalsa University Act, 2016, under which Khalsa University was established in Amritsar in the same premises as the historic Khalsa College established in 1892.

In the case Khalsa University vs the State of Punjab, a two-judge bench of the top court was dealing with a challenge to a division bench order passed by the Punjab and Haryana High Court at Chandigarh, by way of which the HC had dismissed the university’s plea for quashing of the Khalsa University (Repeal) Act, 2017.

ThePrint takes a look at the case and arguments from various sides.

Also Read: Supreme Court letting states subclassify SCs-STs. I call it ‘Constitution amendment by stealth’

Why was Khalsa University Act passed in 2016?

In 2010, Punjab framed the Punjab Private Universities Policy, on the basis of which a charitable society named ‘Khalsa College Charitable Society, Amritsar’ submitted a proposal to the state government for setting up a self-financing university.

The policy was set up with the aim of attracting “high-quality private sector investment and expertise” in the higher education sector. Under the 2010 policy, the Punjab government permitted the establishment of self-financed universities, which wouldn’t receive any grant or aid from it. It also provided for laying down a rationale proposal and well-defined conditions for the establishment of such universities to safeguard interests of stakeholders, former students, staff members, and genuine promoters.

The following year, in 2011, the higher education department of the Punjab government issued a letter of intent to Khalsa College Charitable Society for establishing and running Khalsa University in Amritsar under the 2010 policy.

Five years later, the Punjab Vidhan Sabha passed the Khalsa University Act, which was notified in November 2016 and sought to “establish and incorporate a University in the State of Punjab to be known as the Khalsa University for the purposes of making provisions for instruction, teaching, education, research, training and related activities at all levels in disciplines of higher education, including professional, medical, technical, general education, language and literature” and matters connected with it.

How did the matter reach SC?

After its establishment, the university started imparting studies in 26 programmes and admitted 215 students for its first academic session.

A few months later, in January 2017, the university registrar informed the principal secretary of the department of higher education that Khalsa University had been established in accordance with the 2010 policy, the 2016 Act, and University Grants Commission (UGC) guidelines.

A month later, the university received a communication from the UGC, informing it that its name was included in the list maintained by the UGC and that it was required to follow the UGC (Establishment of and Maintenance of Standards in Private Universities) Regulations, 2003.

The issue, however, got complicated following a change in the Punjab government in March that year. From April 2017 onwards, the university started receiving communications that it shouldn’t admit more students till its statute was approved by the government.

On 30 May, 2017, Punjab government passed an ordinance to repeal the 2016 Act. This ordinance was followed by the Khalsa University (Repeal) Act, which received Governor’s assent in July 2017.

Challenging the communications from the department of higher education, along with the 2017 ordinance, Khalsa University and the Khalsa College Charitable Society filed a plea before the Punjab and Haryana HC. However, the HC dismissed this petition on 1 November, 2017.

What was the university’s case?

In its plea, Khalsa University challenged the Khalsa University (Repeal) Act, 2017, as patently arbitrary, mala fide, discriminatory and violative of Article 14 of the Constitution.

Indicating that the decision had ulterior political motives, senior advocate P.S. Patwalia said in court that “public statements” made by Captain Amarinder Singh when he was in the Opposition clearly showed that he was opposed to the university’s establishment. For instance, Singh once said he was “touchy” about Khalsa College and wouldn’t allow the ruling party to tinker with its status, according to the advocate.

Immediately after becoming chief minister in March 2017, Amarinder had passed the 2017 ordinance repealing the Khalsa University Act, Patwalia said, adding that the university had been established under the 2010 policy of the Punjab government, alongside 15 other private universities.

Stating that out of all 16 universities set up under the 2010 policy, Khalsa University was the only one that was picked up and abolished, Patwalia dubbed the action as “arbitrary”.

Referring to the objective laid down in the repealing legislation, which was purportedly “to protect the heritage character of Khalsa College”, the petitioners argued that these objectives indicate that the 2017 Act was passed on the basis that Khalsa College has, over a period of time, become a significant icon of Khalsa heritage and the university, established in 2016, was likely to shadow and damage its character and glory.

Besides contending that Khalsa College was established in 1892 and the university over a half-century later, the petitioners gave an undertaking that the university’s establishment wouldn’t affect Khalsa College. The petitioners also said that the university was established to provide affiliation for just three colleges, namely Khalsa College of Pharmacy, Khalsa College of Education and Khalsa College for Women.

Relying on the top court’s 2017 ruling in Shayara Bano vs Union of India, where the court said the ground of manifest arbitrariness is also available for examining a legislation’s validity, the petitioners said that if a legislative enactment isn’t based on an intelligible differentia, then such a classification wouldn’t be permissible and the enactment would be liable to be struck down on grounds of manifest arbitrariness.

What was the state’s defence?

Appearing on behalf of the Punjab government in the SC, Additional Advocate General Shadan Farasat said that merely because Khalsa University was singled out against other universities under the 2010 policy, the same cannot be a ground for declaring the 2017 repeal Act as invalid.

Pointing to the inherent presumption of validity of a legislative action, the state contended that the burden with regard to proving invalidity, in such cases, would lie on the one challenging it.

Underlining that Khalsa College, over a period, received its heritage status, it added that the name “Khalsa” was associated with the college, and the university’s establishment tinkered with its heritage.

Emphasising that both the college and the university were established in the same premises, leading to possible confusion in the minds of general observers, it said the college had earned a huge reputation and the setting up of the private university could diminish it’s stature and lead to the possibility of Khalsa College Charitable Society allocating greater attention and resources to the latter while neglecting the former with its historic value.

Finally, the Punjab government said the petitioners had no vested right, and shortly after the 2016 Act was enacted, the 2017 repeal Act followed. During that short period, a few students were admitted to the university, the state said, while adding that it had taken care of these students, as the colleges they were studying in had got affiliated with other universities.

What did the top court rule?

Saying that the 2017 Act was brought about with the “sole purpose of repealing the 2016” law, the SC said it was clear that it dealt with only a single entity, that is, Khalsa University.

Underlining that it did not wish to go into the allegations of mala fides attributed to any individual involved in the passage of the repeal Act, the two-judge bench demarcated two questions for consideration in the case.

The first was, whether an enactment giving differential treatment to a single entity would be valid in law. The second was whether the 2017 Act was liable to be struck down on grounds of arbitrariness.

Would a law giving differential treatment to a single entity be valid?

Concerning the first question, the court relied on its 1950 ruling by a five-judge bench in Chiranjit Lal Chowdhuri vs Union of India, where it was faced with a situation where the Governor General had promulgated an ordinance on the basis of a finding that, mismanagement and neglect at Sholapur Spinning and Weaving Company had not only affected the production of an essential commodity, but also led to serious unemployment.

Subsequently, Sholapur Spinning and Weaving Company (Emergency Provisions) Act, 1950, was passed, which led to the dismissal of the mill’s staff.

Later, when the Act was challenged before the SC, one of the grounds for challenge was the application of the legislation to just one entity, and consequently, its discriminatory character, which was violative of Article 14. However, by a 3:2 majority, this ground was rejected by the constitution bench, given the totality of the circumstances in the case, and the situation being of an extraordinary character.

Although other companies were open to charges of mismanagement, the criterion by the government for singling out Sholapur mills could not be said to be arbitrary or unreasonable, the court said.

In its 65-page ruling, the bench clarified that there can certainly be a law that applies to one person or group, and the same cannot be held to be unconstitutional if it isn’t discriminatory in its character. However, the court said that had it been a bad law that arbitrarily selected one individual, class, or corporation and penalised them in a way that wouldn’t apply to others, its validity could be in question.

Answering the first question in the Khalsa University case in the affirmative, the apex court Thursday said that though the Punjab government had filed a reply in the present case, it did not deal with the petitioner’s arguments on discrimination. It also pointed out that no material was placed on record detailing the “compelling and emergent situations” that necessitated the enactment of the 2017 Act.

“We therefore find that the impugned Act singled out Khalsa University (appellant No.1) among 16 private universities in the state and no reasonable classification has been pointed out to discriminate Khalsa University (appellant No.1) against the other private universities,” the bench ruled, while dubbing the Act as discriminatory and violative of Article 14.

Can 2017 Act be struck down on grounds of arbitrariness?

On the second ground of challenge, which was that the Act suffered from “manifest arbitrariness”, the court explained that “manifest arbitrariness must be something done by the legislature capriciously, irrationally and/or without adequate determining principle”, as laid down in the 2017 Shayara Bano case.

The bench also said that the “only reasoning” given in the Act’s objectives was that over a period of time, Khalsa College had become a significant icon of Khalsa heritage and the university was likely to shadow and damage its character and glory.

However, it clarified that “Khalsa College which was established in 1892 is not a part of Khalsa University”. The same was evidenced by the undertaking furnished by the university that its establishment wouldn’t touch or adversely affect the college.

Even during the course of hearing, a specific statement has been made by the appellants that Khalsa College would not be affiliated with Khalsa University, the court said, while adding that maps had been placed in the college campus “clearly” revealing only the college built in 1892 was a heritage one, while all other buildings were later constructed.

“It can thus be seen that the very foundation that Khalsa University would shadow and damage the character and pristine glory of Khalsa College which has, over a period of time, become a significant icon of Khalsa heritage, is on a non-existent basis,” the court said, adding that the purpose of the 2017 Act was in fact “non-existent”, suffered from manifest arbitrariness and violated Article 14.

“We are therefore of the considered view that the impugned Act is also liable to be set aside on the same ground,” the apex court said in its ruling, striking down the 2017 law.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)