New Delhi: The upcoming assembly elections this month in Uttar Pradesh and Punjab are important for various political reasons, but they also mark a significant historical milestone.

In March 1952, Punjab and UP were among a list of 22 states that held legislative assembly elections for the first time. The polls in 2022, therefore, coincide with the 70th anniversary of assembly elections in these states.

According to Election Commission of India (ECI) reports, the first general and assembly elections in independent India took place between October 1951 and March 1952. Many of the other states from that time — including Bombay, Saurashtra, Hyderabad, and Madhya Bharat — have since been reorganised. Bihar, Odisha, and West Bengal had also voted in March 1952, but don’t have elections scheduled for this year. Manipur, which is also going to polls in February-March, was a Part C state then, which meant it did not vote for a legislative assembly at the time.

Punjab and UP have also seen some changes since the time of the first elections. In 1956, the Patiala and East Punjab States Union, which encompassed several princely states, was integrated with Punjab, and in 1966, some hilly parts of Punjab were merged into Himachal; that year, Haryana too was carved out of East Punjab. Uttar Pradesh has also changed shape, with Uttarakhand being carved out of it in 2000.

Nevertheless, elections for the assemblies in these two states will soon complete 70 years, with Punjab voting on 14 February and UP in seven phases from 10 February to 7 March. ThePrint takes a look at the nascent days of India at the polls.

Also Read: All the noise on Indian democracy hides the silence on idea of republic. It’s unhealthy

Setting the stage for independent India to vote

The Representation of the People Act, 1950 and 51 laid the ground rules for the first elections in independent India, providing for the delimitation of constituencies, preparation of electoral rolls, details of the system of conducting the polls, and so on.

The Election Commission of India was formed on 25 January 1950 (a day before the Constitution came into effect), with Sukumar Sen appointed as its first commissioner soon afterwards, but the making of the electoral rolls had already been initiated by the Constituent Assembly in 1948-49. In her book How India Became Democratic, writer Ornit Shani noted an interesting truth: “Indians were voters before they became citizens.”

A June 1952 article in the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) further observed that neither “parliamentary institutions nor the principle of election” were “new to India”. The concept of legislative councils had already been introduced in the country by the British in the 19th century. By 1892, elections were also being held to choose a section of members for legislative bodies.

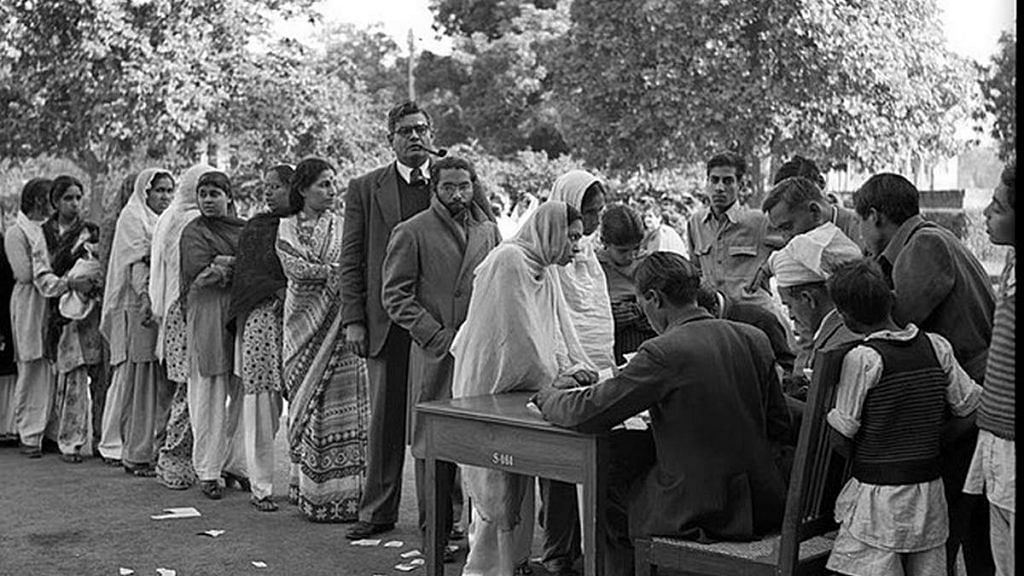

But the general and assembly elections of 1951-52 were novel. This was not only because they were the first polls in independent India, but because of the introduction of universal adult suffrage in the country.

Huge practical challenges

While the idea of every adult citizen having a vote was noble, it posed many challenges for the newly independent country. According to the ECI’s ‘Report on the First General Elections in India (Volume I)’, India had a population of 348 million at the time. Forty-nine per cent enrolled as voters.

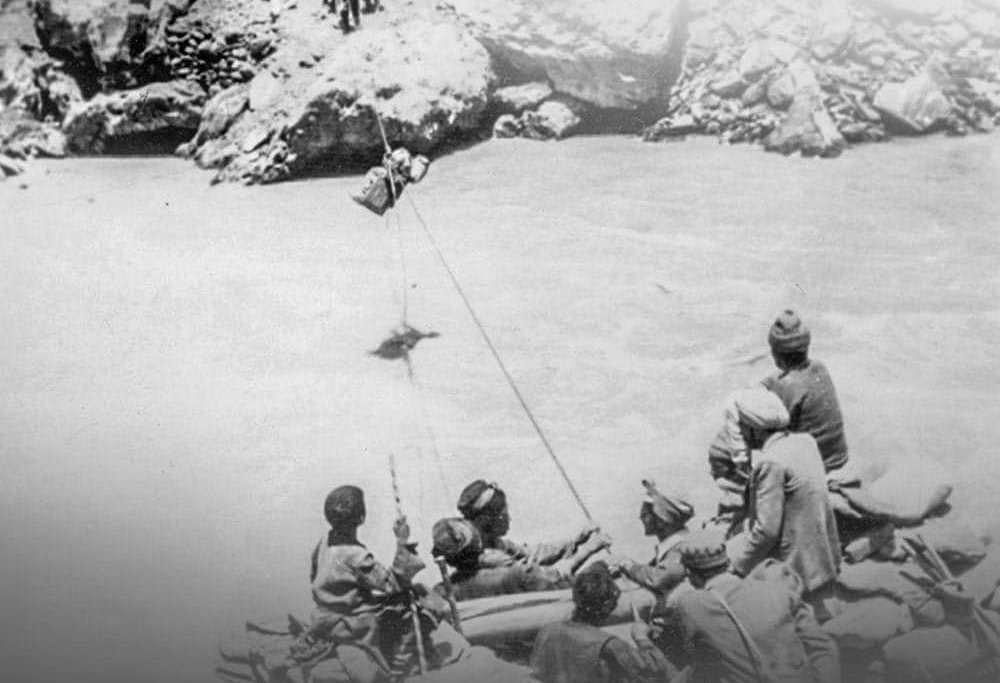

The authorities were determined to ensure that every Indian had the opportunity to exercise their right to vote. But there were logistical issues. Finding trained manpower for the job was in itself a challenge in a country that was still finding its footing. Many regions were remote and had poor connectivity in those days. This posed a problem both while drawing up the voters’ list, as well as during the actual election process.

Partition and the resultant inflow of people, especially in parts of Punjab, Delhi, and West Bengal, too needed to be addressed. The displaced populations were often mobile, moving within the states in search of shelter and livelihood. This added to the problem of drawing up voters’ lists, because there was the danger of the same person being included more than once.

“In Punjab it became necessary to re-check the entries in the rolls prior to preliminary publication so as to eliminate large numbers of obviously duplicate entries therein in respect of displaced persons who had moved from one place to another and been registered in more places than one,” observes the ECI report.

Another challenge faced by the ECI while drawing up the voters list was in identifying women. Many were reluctant to give their names, choosing instead to identify themselves as “wife of” or “daughter of”… . The ECI policies required voters to be listed by name, which resulted in about two to eight million women not being included in the voters’ list, according to the report.

The problem of illiteracy also posed difficulties. In fact, party symbols — synonymous with Indian politics today — were born of the need to solve this problem. “The percentage of literacy in India being in the neighbourhood of 16-6 only, it would have been impossible for the vast majority of voters who are illiterate to mark their votes on ballot papers with the names of contesting candidates printed on them,” explains the ECI report of the 1951-52 elections. Thus, symbols that were recognisable were devised for voters.

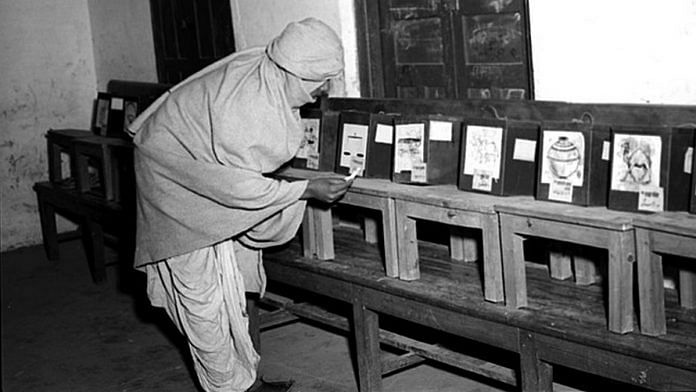

The scale of independent India’s first general and assembly election can be gauged from the fact that it required 25,84,945 ballot boxes, six hundred million ballot papers and 3,89,816 phials of indelible ink. The total cost of elections came to Rs 10.45 crore.

Also Read: As EVMs are debated, this is how the ballot box was made for India’s first 1952 election

Reaching the people: bullock carts for campaigning, no radio allowed

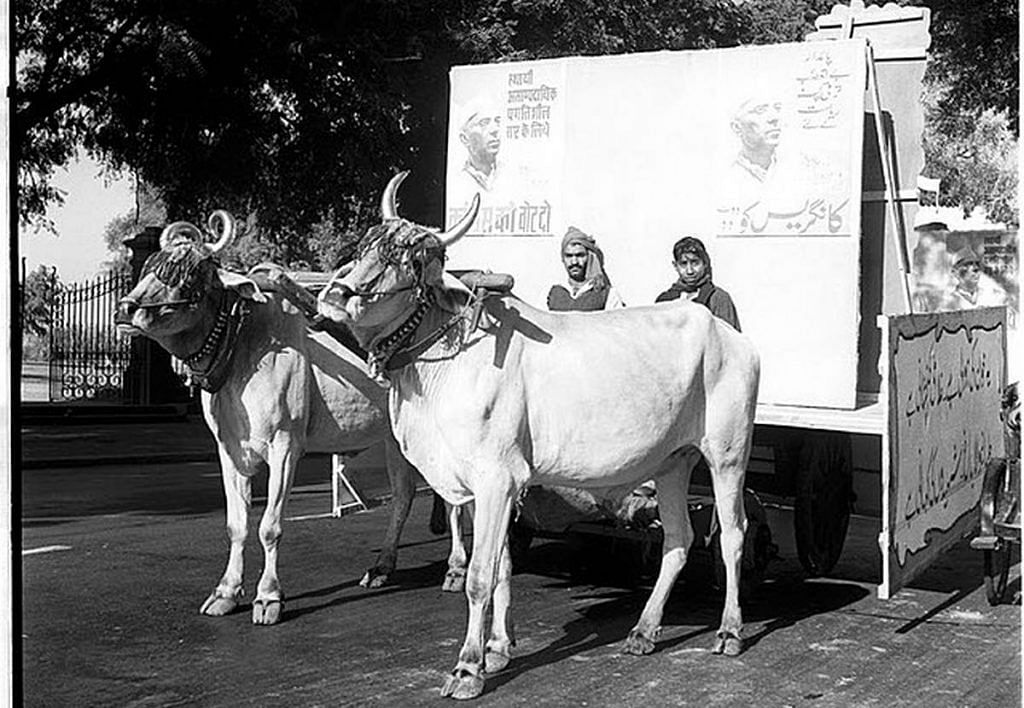

Canvassing for the 1951-52 election was all about establishing a face-to-face connect between parties and the people, a far cry from the social media and digital campaigns of the present.

In fact, in 1952-53, parties were not even allowed to use the radio to reach voters, although the ECI did use the medium to spread awareness about the impending elections.

“A question was raised whether broadcasting facilities should be made available to the parties for their election propaganda… the matter became too controversial and the Election Commission advised the government that it would be almost an impossibility to apportion broadcasting facilities amongst the numerous ‘recognised’ parties with reasonable fairness and to the general satisfaction of the public,” the ECI report elaborates.

With a permitted expenditure of Rs 4,000-16,000 per assembly constituency — depending on the number of representatives to be elected from a particular constituency, India had one-, two- and three-member constituencies then and Rs 25,000-40,000 per parliamentary constituency — the parties had limited means at their disposal.

“It is said party leaders used to travel by cycles, bullock carts and tongas (horse carriages) for campaigning. Some jeeps were used, but they were mostly used cars. If they got delayed while campaigning in villages, they would spend the night at any local party worker’s home,” Professor Pankaj Kumar, head of political science department, Allahabad University, said.

In addition to the efforts of the ECI and political parties, the press also played a major role in building awareness about the elections. “As many as 397 newspapers were started during the period of the elections and most of them ceased to exist after the elections were over,” the ECI report notes.

A brief era of ‘positive’ campaigns

“The first election was all about Nehru. Of course, there were opposition parties, but their numerical strength was very low,” Professor Pankaj Kumar said.

In an article published last year, political commentator and professor at Allahabad’s Govind Ballabh Pant Social Science Institute, Badri Narayan, wrote about the campaigning in Nehru’s Phoolpur constituency in UP ahead of the 1951-52 elections.

“It is interesting to remember when Nehru contested the first election in 1952, two main issues dominated the social and political debates. One was the dream and desire to make the future India free of poverty, develop a ‘sukhi (pleasant) India’; second was the place of Hindus in this idea of India. One part of the election discourse was led by Nehru and his followers, and another by Prabhu Dutt Brahmachari, an independent candidate supported by the Akhil Bharatiya Ram Rajya Parishad and All India Hindu Mahasabha,” Narayan wrote.

The two held opposing views, but as political analyst and professor, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), Sanjay Kumar explained, “for the first two decades after independence, election campaigning was more about parties talking about what they would do if they won the election. It was positive campaigning. Now, it is all about attacking your opponents, denouncing your rivals.”

A Congress sweep in UP and Punjab

Under the provisions of the Representation of People Act 1950, the House of People (or Lok Sabha) had a total of 497 members — UP and Punjab contributed 86 and 18 of these, respectively. The assemblies in these states had 430 and 126 members.

A 1952 statistical report of the ECI records 28 March as the date of polling in UP’s 347 assembly constituencies. Elections were held in the 105 assembly constituencies in Punjab a day earlier, on 27 March. In both states the Congress won by majority — 388 seats in UP and 96 in Punjab.

Interestingly, both states had their first non-Congress chief minister in 1967 — Charan Singh in UP (leading a coalition of the Bharatiya Kranti Dal, Jana Sangh, CPI(M), Republican Party of India, Swatantra Party and Praja Socialist Party) and the Akali Dal’s Gurnam Singh in Punjab.

Also Read: ‘This govt is of Ram bhakts, and Gita is above the Constitution’—Inside Modi’s India