In the pristine labs at Phyx44 in Bengaluru, a shiny hundred-litre fermenter tank pours out gallons of milk. The creamy white frothy liquid is chemically identical to the milk we get from cows and buffaloes, but its origins are very different. No animal was touched to produce this milk. It’s the result of ‘smart proteins’.

A genetic code that tells the cow’s body how to produce milk was introduced inside microbes, which then churned out the proteins that are essential components of milk.

Around 200 km away in the neighbouring city of Mysuru, another startup, Mycovation, is trying to create proteins found in fungi, which can then be added to plant-based meats to improve their taste and texture. Their team uses filamentous fibres of fungi for this purpose.

Startups like Phyx44 and Mycovation are poised to capitalise on food trends in a world bogged down by climate change, where the cruelty-free tag is displayed like a medal, and veganism has stormed mainstream culture. They are part of a larger global movement in the alternative protein industry called precision fermentation. The idea is to get as close to the taste of the ‘real thing’ as possible – without harming or depending on animals in the process.

“We are trying to get milk and milk products that are identical to what you get from the cow but without using animals,” Phyxx44 founder Bharath Bakaraju said.

Most of the startups are a long way off from mass production, but the technology holds the seed of a promise—a world without industrialised rearing of cattle, with reduced greenhouse emissions from agricultural and animal rearing practices, and one that is less vulnerable to the vagaries of climate change. But it has the potential to disrupt the dairy industry, already there is pushback. And first, Phyx44 and other startups have to convince vegans that the product is truly cruelty-free.

Ever since Dutch professor and pharmacologist Mark Post unveiled the world’s first hamburger made from lab-grown beef that costed more than $ 300,000 ten years ago, there’s been a growing interest in cellular agriculture. Cells are being engineered to generate proteins. A startup in the US used cells to produce lactose and casein found in breast milk. Another startup, also in the US, is using the process to develop animal-free eggs.

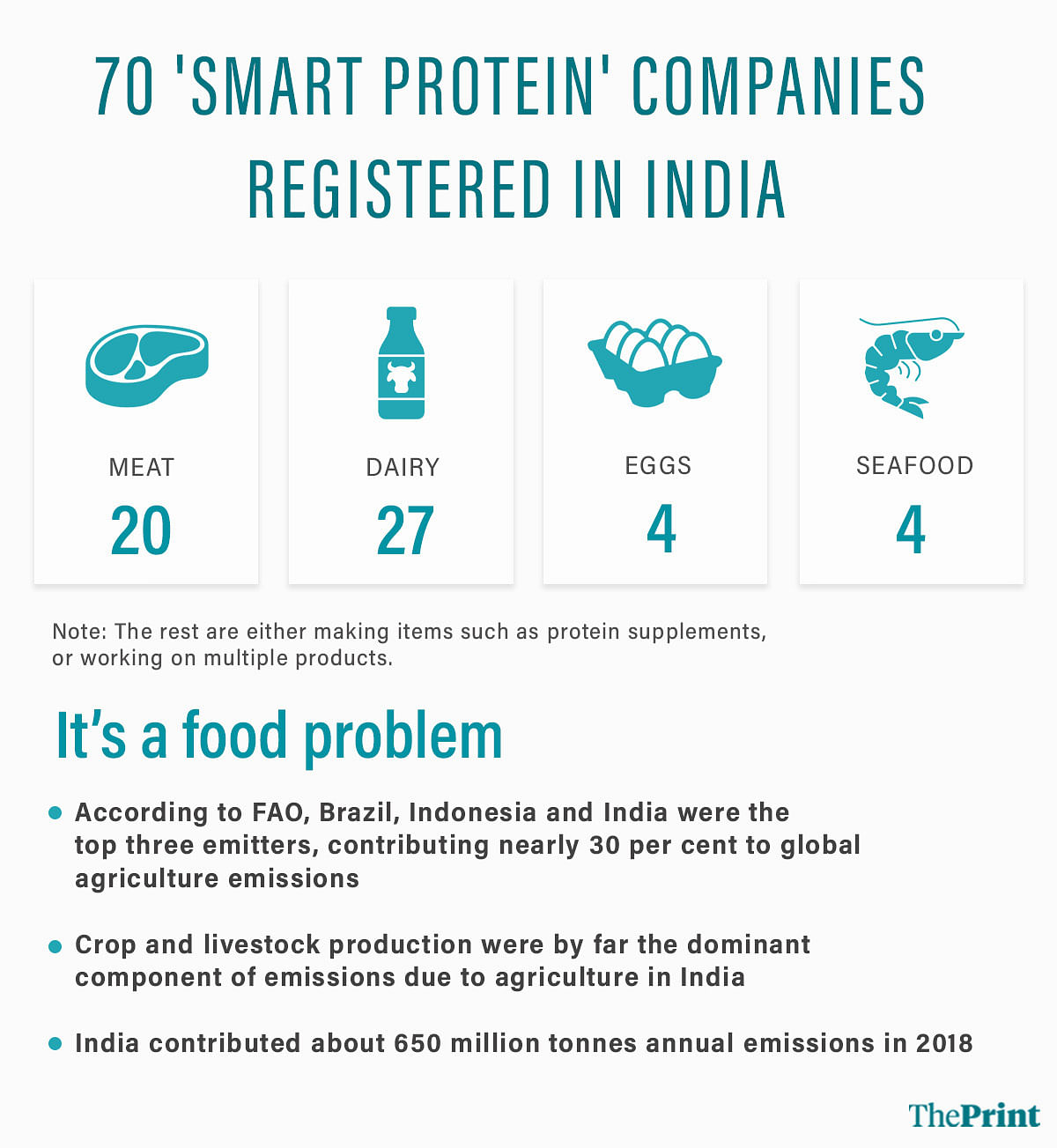

At the centre of this movement in India toward alternative proteins is the Good Food Institute (GFI) India, a wing of international nonprofit think tank GFI that works towards accelerating research, policy, and business in this space.

In India, GFI is engaging with government, scientists, and startups to identify research problems, encourage sustainability in food production, and advocate ‘smart’ proteins. But it steers clear of actively advocating veganism. Instead, the technologies involved are marketed as a green, alternate source of food in the backdrop of climate crisis and food insecurity.

“There is not enough land, feedstock, water and labour available to produce animal-based products in a sustainable manner. So we need to rethink how we produce our food, and this is an attempt to look at how the future of foods looks,” Bakaraju said.

Also read: Duties, duties, duties. Modi is going back to the Indira Gandhi Emergency era

From sci-fi to real life

Growing up, Bakaraju loved curd, ghee and paneer, but as an adult vegan, he was unhappy with the alternatives in the market. Phyxx44 is the perfect testing ground for cruelty-free products that don’t compromise on taste.

The team has created strains of microbes to produce casein and whey proteins. This has been scaled to a hundred-litre fermenter tank, and the team is in the process of scaling up to 1,000 litre.

“Our endeavour right now is to be able to scale up the product to be able to do consumer surveys,” Bakaraju said.

Precision fermentation is relatively a new name for a fairly mature technology called recombinant protein production, which has been around for nearly two decades, Bakaraju said. It’s used in the production of vaccines, molecules for biopharmaceuticals and antibody therapies. But using recombinant protein technology to create proteins that are identical to what we get from animals is relatively new.

“Milk is basically a concoction of lactose, proteins, fats, sugars and water. If you look at the protein in milk – there are two very important components: casein and whey,” said Bakaraju. “We want to test our product out for consumers in different forms – whether it is liquid milk, yoghurt, or any other consumer products that can be made and consumed,” he added.

But so far, only one company, Perfect Day, has received approval from India’s food safety regulator (FSSAI) to manufacture animal-free milk protein using the precision fermentation technology. Headquartered in the United States of America, the precision fermentation company received approval for its product in 2020 from the USFDA. In November last year, it acquired Gujarat-based Sterling Biotech to expand its presence in India. The company plans to invest Rs 957 crore to scale up production and export of animal-free milk proteins from India.

The technology has the potential to reduce dependence on livestock, which produces 14.5 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. And India has the potential to become a manufacturing and consumer hub.

The India vegan food market size reached $1,324 million $1.32 billion in 2022, according to a report by The International Market Analysis Research and Consulting (IMARC). It predicts that this will grow to touch $ 2,463 million $2.47 billion by 2028.

What a person chooses to eat is personal. There are also a number of socio-economic factors behind such choices. Our goal is rather to look at food sustainability in the long run

— Mansi Virmani, Good Food Institute, India.

Also read: Odisha is becoming an IAS state. Patnaik-Pandian combo is changing grammar of governance

Smart proteins as a research priority

In August, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Science, Technology, and Innovation Advisory Council (PM-STIAC), chaired by Prof. Ajay Kumar Sood, principal scientific Adviser to the government of India introduced the country’s policy priorities for high-performance biomanufacturing. Smart proteins was one of them.

According to GFI, the Indian government has begun to recognise this potential and is actively engaging with stakeholders to boost the infrastructure for manufacturing smart proteins.

GFI India is now part of a sectoral committee on smart protein working towards a national policy on biomanufacturing. On the ground, GFI is working with research labs to help develop technologies.

“What a person chooses to eat is personal. There are also a number of socio-economic factors behind such choices. Our goal is rather to look at food sustainability in the long run,” said Mansi Virmani of GFI India.

It also offers technical advisory to the startups and companies who are involved in such products. “These include end-product manufacturers, ingredient suppliers, as well as equipment manufacturers,” said Padma Ishwarya, a science and technology specialist at GFI India.

In this, GFI’s goals align with Bakaraju and others who are desperate to address food insecurity, limited resources and a growing population. And the future could well be lab grown meat.

Also read: Bhanwari Devi was raped for trying to stop 1992 child marriage. ‘I curse her daily,’ says bride

Challenges in fermented meat

It begins with broth. Meat protein cannot be fermented like milk because its structure is more complex. Instead, stem cells from a fertilised egg or tissue from a living animal are tested for resilience and their ability to divide, and then frozen. When it’s time to make the meat, they are mixed in a broth of nutrients that are required for the cell to grow and divide.

“But that broth needs certain particular protein ingredients, which comes from precision fermentation,” said Chandana Tekkatte, science & technology Specialist at GFI. That is the crucial link between fermentation and making meat.

Growing meat using the fermentation process is very challenging. Unlike milk and egg – which are largely composed of one or two kinds of proteins – meat has a diverse range of proteins

–Venkatesh V Kareenhalli, a professor at IIT-Bombay

“After a few weeks, the cells begin to adhere to one another and produce enough protein to harvest. Finally, the scientists texturize the meat by mixing, heating or shearing it and press it into nugget or cutlet shape,” said Joanna Thomson in an article in the Scientific American.

India is still a long way off from manufacturing lab-engineered meat for consumption, but research has been underway for several years now. In 2019, the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) allocated Rs 4.5 crore for India’s first government-funded project on cell-based or clean meat. The Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) in Hyderabad partnered with the National Research Centre on Meat for the project.

Venkatesh V Kareenhalli, a professor at IIT-Bombay, is trying to take a different approach to producing proteins for human consumption that can mimic meat. He has identified algae that typically grows in north eastern states to produce proteins.

“Growing meat using the fermentation process is very challenging. Unlike milk and egg – which are largely composed of one or two kinds of proteins – meat has a diverse range of proteins,” Kareenhalli told ThePrint.

The texture and mouthfeel of animal meat comes from the muscle cells – which need a different process to grow. “While labs around the world are trying to culture cells in the lab to ‘grow’ meat – this is proving to be unviable and expensive,” he said. Moreover, with current technological knowledge – there is no substitute for blood serum obtained from animals. So, cultured meat cannot be ‘vegan’, he argues.

His team has managed to tweak the alga to produce up to 1 kilogramme of proteins per day. At present, this product can be used as animal feed, but the team is working to make it fit for human consumption.

“The process also uses carbon dioxide – and right now the world is looking for carbon remediation,” he added. This makes the proteins sustainable.

Kareenhalli has also developed oyster mushrooms to produce proteins that are closer to animal meat.

“Eventually, we will see if we can somehow blend the two to get the right product that tastes and feels like meat,” he added.

Catering to a vegan market is not the ultimate goal – what he wants to achieve is a new generation of ‘functional foods’, that have high nutritional or medicinal value.

“We can make a food that diabetics can consume or for cancer patients who require immunity and proteins for recovery after their therapy,” he said.

In the private sector, startups like FermBox, a synthetic biology company, uses precision fermentation technology with particular emphasis on animal-free fat ingredients for food applications. This includes fermentation-derived animal and dairy fats, lipids, colouring agents, flavour molecules. The FermBox facility is currently only 40,000 litres and will be scaled up further.

Also read: Kerala’s indie films are stuck in bureaucratic belly. No theatre fans or OTT buyers

Changing mindsets and labels

The puritanical and the pedantic can argue that lab-cultivated meat and milk is not truly vegan, but the end-result is cruelty-free. And dairy-loving Indians are slowly embracing the vegan life from ethical leather to oat milk and almond butter.

Vegan is the flavour of the season. GFI considers 2021 to be a banner year for investments, with $5.1 billion poured into the category. From 2019 to 2021, over 400 products and 60 brands are working on plant-based meat, eggs, and dairy with many of them launching on shoe-string budgets. At the same time, FMCG titans like Tata Consumer Products and ITC, as well as D2C (direct to consumers) unicorn Licious have also launched their own line of plant-based meats, thereby demonstrating an early proof-of-concept for the sector in India.

Lab-grown meat and milk can upend this sector, but it’s still very early days. More people are becoming aware that a stomach ache after consuming milk and related products is a sign of lactose intolerance

“When we started off, the plant-based industry was known as the alternative industry. If you think about it, alternative is something that is a second choice,” said Sweta Khandelwal, one of founders of BetterBets (previously AltFoods), which sells plant-based chocolate, vanilla,mango and other flavoured drinks.

Instead of working largely with imported crops, the Noida-based startup decided to go ‘desi’.

“We launched our product made from sprouted sorghum, ragi and oats. It is a one-of-its-kind blend and the first in the entire world to make millet milk,” said Khandewal.

It took hundreds of trials to achieve the right blend, but eventually they got there. Now, BetterBets is a supplier to some major chains in India, including Blue Tokai and Roasteries.

“For Indians, taste matters. If chai does not taste like chai then there is no point having that tea,” said Khandelwal.

However, the market’s mindset has shifted drastically, she added, largely due to pandemic, which made people think about health and what they consume.

“People also had the time to focus on their lifestyle and implement changes during the pandemic,” she added.

But none of these alternative products can be called ‘milk’. In 2021, the FSSAI issued an advisory, prohibiting the use of words like ‘milk’ or ‘dairy’ to classify plant-based beverages, with the exception of certain products like coconut milk and peanut butter. The advisory was in response to a complaint by the National Co-operative Dairy Federation of India (NCDFI), which objected to the classification of plant-based milk products as dairy.

The “strong milk lobby” has been one of the biggest hurdles to the plant-based dairy industry in India, according to Virmani. NCDFI had called private companies labelling plant-based beverages as milk to be ‘illegal’. Most dairy cooperatives in India — including Amul and Safal — are members of NCDFI.

“We have to adapt to regulatory changes. We have to educate our customers. For us the main problem was that when someone hears millet milk they understand what it is, but if we call it a drink – they might think it’s a juice or something,” said Khandelwal.

Marketing using the correct labels matters to BetterBets because millets have traditionally not been thought of as tasty ingredients in India.

While plant-based products still have a clear regulatory framework, the road is somewhat foggy for fermented foods like lab grown meat and milk.

“Companies working aren’t quite sure what sort of inputs they should be using to create their end product to make sure it is compatible with local regulatory guidelines,” said Tekkatte, science & technology specialist at GFI.

Foods produced using precision fermentation currently fall under the category of ‘novel foods’, which need to be evaluated by the Scientific Panel of the FSSAI. If the safety of the novel food is established, it can be approved for consumption in India.

“This is a story where India innovates and manufactures for the world,” said Bakaraju.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)