In recent weeks, senior Indian political leaders have made many ‘pseudoscientific’ claims, passing them off as facts. Tripura chief minister Biplab Deb said the internet existed during the times of the Mahabharata. Science and technology minister Harsh Vardhan said Stephen Hawking believed the Vedas contained formulae about the universe that were superior to Einstein’s.

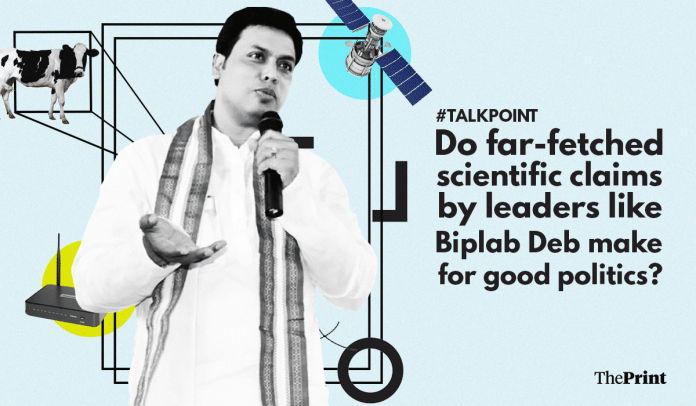

ThePrint asks: Do far-fetched scientific claims by leaders like Biplab Deb make for good politics?

Indians need to find a way to validate home-grown systems under the bigger lens of what is knowledge

Jaya Ramchandani

Jaya Ramchandani

Science educator, entrepreneur

Touch the cold exterior of your laptop with one hand and a book with the other. Which feels cooler? But if you take a thermometer and measure the temperature of both surfaces, you’ll find that they’re the same! So, if you believe something, and I am able to change your mind through reason or experience, and break your misconception, there is a higher likelihood of the new understanding sticking.

Pseudoscience is a belief mistakenly regarded as being based on science and a misconception is a view that is incorrect based on faulty understanding. “Darwin’s theory is scientifically wrong. Nobody said they ever saw an ape turning into a man,” higher education minister, Satyapal Singh had said. He clearly needs some coaching on what is the scientific method and what about the evolution story is scientific.

Similar comments have been made by BJP MP Ramesh Nishank who said: “Astrology is the biggest science.” This is not unique to India. One of the greatest misconceptions around science, in fact, seems to be the misconception about what science is in the first place!

I’d much prefer if the media used these instances as an opportunity to tackle more systemic problems, rather than saying “oh look our politicians are so silly”, that’s counter-productive behaviour. Journalists can instead look at the question of qualification or training required for someone to become a higher education minister. What is the minimum competency? How can gaps of knowledge be made smaller? How to facilitate and stimulate dialogue to upskill our political cadre?

Journalists and the media should perhaps shift focus from the politician to the problem. If I read all of the past comments by politicians together, I find a bigger systemic problem that can be focused on—that of deep insecurity stemming from deep oppression. We need to find a way, as Indians, to validate our home-grown knowledge systems (whether old or new) under the bigger lens of what is knowledge.

A careful watch needs to be kept on what elected officials and ministers say about science so that it doesn’t slip into science

Pavan Srinath

Pavan Srinath

Fellow and faculty member, Takshashila Institution

Pseudoscience and pseudohistory do seem to make for good politics in India today. If nothing else, they make for good publicity— for there is no such thing as bad publicity. India is not currently in a position to be globally best at something, be it the first to go to Mars, or building the biggest ship, or having the best companies. Some feel the need to fake past achievements in order to fill this gap— and pseudoscientific achievements of ancient India make for stories that refuse to die.

However, a careful watch needs to be kept on what elected officials and ministers say about science. The slope between rhetoric and policy is slippery. It is easy for serving officials to curry favour by promoting pseudoscience as priority areas for research funding. Given the dire state of science research funding in India today, it is easy to lose sight of the broader scientific goals India needs to pursue.

It is also important to track how scientific input is used to make government policies. From climate to energy to public services, we need elected representatives who are receptive to scientific evidence, especially when it clashes with conventional wisdom or dogma.

We also need to keep asking elected officials what they are doing to promote the cause of science. Apart from oversight of the government’s budget and activities, each member of the parliament and assembly gets discretionary funding amounting to a few crores every year. Why isn’t any of it being spent on museums, libraries, and science labs? The words and actions of the politicians matter, and deserve constant scrutiny.

When a Biplab Deb talks about Mahabharata-era internet, he is just trying to feed a particular constituency

Rahul Siddharthan

Rahul Siddharthan

Computational biologist, Institute of Mathematical Sciences, Chennai

“Don’t feed the troll” is a common saying since the early days of the internet. That is, there are some who ‘troll’ for responses by deliberately provoking. Don’t encourage them by responding. But what if the troll is a minister spouting pseudoscience? Such politicians have existed since Independence, and some may genuinely believe what they say. But I suspect that when a Biplab Deb talks about Mahabharata-era internet, he is just trying to feed some particular constituency.

Such statements have become particularly numerous in the recent years. Should scientists and the media be responding to each such claim?

But why would anyone believe Deb? “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” Arthur C. Clarke, technologist and science fiction writer, wrote. For many, the internet is magic, and even the educated have very little idea how it works. Even for those who know vaguely about modern wireless digital communication technology, it may seem plausible that a different ancient technology could enable something similar.

It is difficult and probably ineffective to firefight so many such utterances individually. The better solution is to educate society as a whole about modern science and technology and how it works, at least at a basic level. This will be a long, hard process and as principal scientific advisor K. Vijay Raghavan has said, cannot be done in the English language alone.

Scientists, technologists, science historians, and elite science educators need to engage with the education system at all levels.

It will be a pity if the ancient contributions of Sushruta and Charaka to medicine are ignored amid claims of Ganesha being proof of ancient plastic surgery; or if the very real contributions of Kolkata’s J.C. Bose to modern wireless communications are forgotten amid claims of a mythical ancient Indian internet.

The ‘glories’ of the past being talked about by leaders like Biplab Deb are just coded appeals to the ‘greatness’ of the caste system

Alok Prasanna Kumar

Alok Prasanna Kumar

Advocate, Bengaluru

Biplab Kumar Deb is the new Yogi Adityanath— at least in so far as filling the role of BJP-chief-minister-prone-to-shooting-his-mouth-off-over-things-he-has-no-idea-about is concerned, be it science, economics, or technology.

Mostly, this is just plain irritating. He tends to say the kind of stuff that upper caste uncles of a certain vintage tend to say at weddings, gatherings or any occasion when they think they have an audience. That a somewhat younger politician in a party of upper caste uncles tends to do so is hardly the stuff of news, or even noteworthy. But, it is easy for television channels to stretch this out because it requires no effort to generate eyeballs, and will feed an outrage cycle or two.

But beyond the media coverage, there is something else at play here and that is perhaps worth debating and discussing. There’s a fundamental paradox at the heart of present-day Hindutva ideology that statements such as these bring out. The paradox is in what the modern Hindutva wants— an India with 21st-century technology and economy, but living in the 12th-century society.

The ‘glories’ of the past being talked about are nothing more than coded appeals to the ‘greatness’ of the caste system. But there is also a realisation that this caste system did not lead to many innovations in technology and science which shaped the modern world as we know it. So, a story is invented. Ganesha was an example of plastic surgery. Pushpaka vimana was a jet plane. They had the internet in the Vedic age. These comforting lies might help upper caste uncles deal with their diminished social standing, but they surely cannot resolve the irresolvable paradox at the heart of the BJP’s Hindutva.

As we laugh at Biplab Deb over his comments, his political base gets strengthened

Sandhya Ramesh

Senior assistant editor (science) at ThePrint

Pseudoscience has been a great and effective political tool in 2018. Not because of who makes grandiose and incorrect statements but because of how we react to them. Keeping a tab on what ministers have to say about any issue is important. However, giving them disproportionate attention is a futile exercise.

Thanks to centuries of oppression, India today lacks a scientific temper. The researchers, scientists, writers, and journalists we see around us are among the privileged, well-educated elite who have broken out of our systems of superstition and ignorance. Even some well-educated scientists follow not only religious practices, which they should be free to do, but also irrational superstitions. Thus, expecting a minister who hasn’t been a part of the scientific vein to be making scientifically accurate statements is rather useless.

Furthermore, ministers say things to please their constituents as well. Making false statements about India’s glorious past and equating mythology to imaginary scientific grandeur isn’t unique to one party or even one decade in our history since independence. Incessantly calling out ministers and hounding them tends to alienate the very base we would like to see changed.

CM Biplab Deb has been in the news practically ever since he made his internet-Mahabharata comment. The fact is, he’s always had these views, but now we suddenly accord importance to what he thinks of Diana Hayden, civil engineering, and plenty of other topics he knows nothing about. We do not know his educational background and to expect him to speak like a polished Barack Obama is not only unreasonable but also judgemental towards people who haven’t had the same exposure we’ve been able to afford.

Deb isn’t qualified to speak about these issues but is given a platform to do so. He has every right to say what he wants but especially when he is wrong, his voice is amplified. It makes for good politics for him but is very bad for scientific progress.

While we laugh at his words, his political base gets strengthened because of our reactions.

This isn’t related to politics at all. We should be looking into it because it is our culture.

Harsh Dev Kumar

Secretary, Indian Foundation of Vedic Science

Investigating scientific claims in our ancient textbooks is very important because there has been ample evidence of it in past writings about science and technologies. Sushruta, for example, practised cataract surgery with Jabamukhi Salaka, a curved tool. He also famously attached a prosthetic leg to a queen so that she could walk. In Sushruta Samhita, he outlines procedures performed on patients to operate and remove kidneys stones. None of these contradicts any Western evidence either, these are well documented.

The Vedas make several claims about sophisticated equipment like aeroplanes that at least need an investigation to understand, rather than blatant dismissal. I was able to obtain assistance from the Sri Lankan government to identify locations mentioned in Ramayana and to examine sites to understand if they look like places where a flying craft could have landed or taken off.

This kind of investigation isn’t new to India either. Western countries have also performed research into their past texts and preserved their records. That’s how we know Greeks made so much progress in science. We also know Indians did, but because a large part of our history was replaced by a colonial narrative, we lost some knowledge. Even in recent history, we have records of the British coming over and performing smallpox tests in Calcutta in the late 1700s. There has always been such knowledge transfer.

I do not fully agree with Biplab Deb’s statements on the internet being available during the Mahabharata-era. But we must remember two things: One, that there are descriptions of technology we do not understand in our religious works. The Ramayana describes objects that are equivalents of war tanks. Some people say that there exist ancient works that describe what we think is a television. There’s no evidence yet, but we haven’t really even looked into it.

Two, people simplify things when explaining. Instead of going into technical details, it is just simple to say that something was the equivalent of the internet. On ancient Japanese and Indian shores, ships were tracked using rows and rows of mirrors over kilometres. It is possible that something like that was being used. But when speaking to the public, such concepts can be simplified and said with modern day examples to get the message across.

This isn’t related to politics at all. Anyone should be looking into it because it is part of our culture. Even if this is the Congress or the BJP or whoever, it is a part of our culture. Why would they not realise that they can tap into this discourse as well? They do! Ministers from all parties have made such claims, there is nothing new or unique.

Compiled by Sandhya Ramesh.

Illustration by Siddhant Gupta.