Mumbai: Every monsoon, trekkers, vloggers and social media influencers used to pack their bags and head over to the Irshalgad fortress — a popular destination in Maharashtra.

The picturesque hill of Irshalgad, around 3,700 feet above sea level in the Sahyadri ranges of the Western Ghats, is situated between Panvel and Matheran and is easily accessible from Mumbai and Pune.

For trekking enthusiasts, Irshalwadi, a hamlet on the foothills of Irshagad, was a halt for breaks and refreshments.

However, on a dark and rainy night last month, rolling mud and rocks swallowed Irshalwadi and wiped it off the map.

The 19 July landslide of Irshalwadi in Khalapur taluka of Raigad district affected 48 families.

Of the 228 people who resided in the village, the bodies of 27 were recovered from the debris, while 57 people were declared untraceable. The rest survived the tragedy.

Of Kamlu Pardhi’s family, five perished in the landslide, while four could be rescued. “My wife, son, daughter-in-law and two grandchildren are buried there. Their bodies may now have decomposed and one cannot even identify them. It is better they rest there,” he told the media.

This monsoon, Raigad received nearly 67 per cent of the annual average rainfall till 26 July, according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), and the district has continued to oscillate between red and orange alerts — extremely heavy to heavy rainfall — the last 10 days of July.

After the Irshalwadi tragedy, nearly 7,000 people from 2,040 families were shifted from 103 landslide-prone villages in Raigad district to 51 camps.

ThePrint reached out to Yogesh Mhase, Raigad district collector, over the phone with queries on the subject but had not received a response at the time of publishing this report. This story will be updated if and when a response is received.

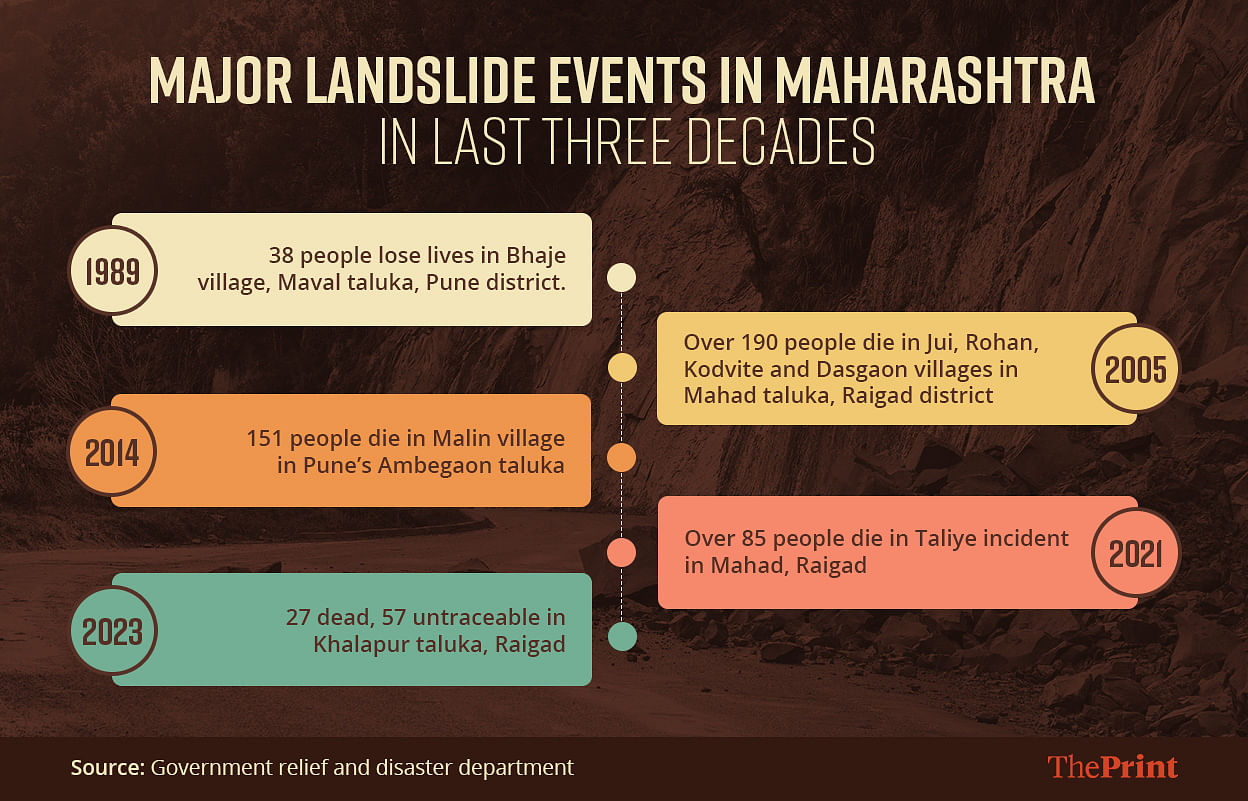

But this incident is not the first of its kind during monsoons in Maharashtra. This is a repeat of what happened in Mahad in 2005, in Malin in 2014, and in Taliye in 2021.

There are striking similarities between these landslides and certain lessons to be learnt in order to avoid such calamities in the hilly areas of western Maharashtra and the Konkan region.

Dr Satish Thigale, former head of the geology department at Savitribai Phule Pune University, told ThePrint that he has been studying landslides since 1983. According to him, landslides in a particular area show signs of its approach — such as cracks in mountains and mud flowing along with water — years, months, weeks, and even hours during heavy rainfall before the actual event.

“But the seriousness of this was never understood and, hence, over the past three decades, we have seen hundreds of landslide incidents in Maharashtra that have claimed lives, destroyed families, and livelihoods. Villages such as Jui, Dasgaon, Malin, Taliye and now Irshalwadi have been wiped off the map. To prevent such accidents, it is important to study the Sahyadri (ranges),” he said.

Also Read: ‘Will talk about UCC but…’: Uddhav tells Modi govt to ban cow slaughter, restore peace in Manipur

Pattern emerges?

Since the 1980s, Raigad and Konkan in Maharashtra have witnessed major landslide tragedies in the monsoon season. Such extreme events have become more frequent due to climate change impact, say experts.

Since 1989, when landslides killed 38 people in Bhaje village in Maval taluka, the frequency has only increased. In 2005, 197 people were killed in Jui, Dasgaon, Kodvite and Rohan villages in Raigad’s Mahad taluka.

Nine years later, in 2014, Pune’s Ambegaon taluka’s Malin village got buried under a landslide, killing 151.

In 2021, 89 people lost their lives to a landslide in Taliye village, again in Mahad, Raigad. The Irshalwadi accident came two years later.

Interestingly, these accidents, especially the ones in Malin and Taliye, happened while people were asleep and could not escape. Taliye and Irshalwadi do not even feature as landslide-prone villages in the government’s list prepared before the monsoons of such villages.

Also, there is a pattern to landslide accidents — they all occurred in July, the wettest month for Maharashtra.

For a landslide to occur, continuous rain for three to four days is necessary, said Mayuresh Prabhune, secretary, Centre for Citizen Science (CCS), a Pune-based non-government organisation that tracks landslides.

Rainfall accumulation of more than 600 mm over five days before an incident and more than 200 mm on the last day is required for a landslide to occur, Prabhune said.

“Because of the extreme rainfall for consecutive days, the saturation level is eroded, causing the mud and soil and rocks to fall. Villages are destroyed due to mudflow which buries everything in its path while rolling down the hill,” he said.

Experts have pointed out that human interventions, lack of government accountability, along with climate change have increased the frequency of these landslides.

“These regions are conducive for landslides and human intervention is also increasing with each passing day. So the psychology of all stakeholders, especially the policymakers and bureaucracy, needs to change for such things to be avoided,” said Dr Thigale.

He told ThePrint that he was part of a committee formed after the Taliye incident in September 2021. The committee consisted of experts and bureaucrats and was formed to study how deforestation, encroachments, and other reasons lead to to increased landslide occurrences. “One meeting was held in April 2022 but we don’t know what happened to the committee after that,” Dr Thigale said.

Possible solutions

The Malin event was a wake-up call. It raised concerns about the safety of people residing in such landslide-prone areas, Prabhune said. The CCS started tracking and studying the landslide events post that.

After the Irshalwadi accident, Congress state head Nana Patole called for the need to implement the report submitted by the Gadgil committee — lead by eminent ecologist Madhav Gagil — which was prepared in 2011 for the Western Ghats, and suggested ways to enable local people to track what was going on environmentally and increase their participation in disaster-mitigation activities.

It also suggested a bottom-to-top approach instead of a top-to-bottom approach in governance of the environment, indicating decentralisation and more powers to local authorities.

“It is important to invite the opinion of the public and local bodies, especially the zilla panchayats, village-level political bodies and also other civil society groups, to enlist the areas that they feel are ecologically and environmentally sensitive, and use these as important attributes,” the report suggested, a copy of which ThePrint has accessed.

It suggested dividing the Western Ghats into three ecologically sensitive zones and recommended the establishment of a Western Ghats Ecology Authority under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, as a professional body to manage the ecology of the region and to ensure its sustainable development.

This report was spread across six states but the stakeholder states reportedly resisted the implementation of the report. They feared it would hinder development since over 50 per cent of the designated area would fall under ecological sensitive zones as per the report’s recommendation.

According to experts, it is necessary to read the signs of landslides and vital to inform villagers about how to tackle these incidents.

Prabhune said one of the signs of a landslide-prone mountain is green cover on the hilltop, which means the hill is covered with soil. But the local administration that works with the Geological Survey of India (GSI) usually only pays visits to villages that have been mapped as landslide-prone to prepare and warn the residents there.

“By going to each village and checking the cracks, how many can you cover? There are limitations to this. The scope needs to be widened. If it is raining heavily, villages which might not even be visited by the GSI or tagged as landslide-prone should be evacuated, just like a cyclone event so that more lives can be saved,” said Prabhune.

According to Dr Thigale, people residing on the foothills of a mountain or on the slope need to look for certain signs, such as development of new cracks, waterfalls carrying mud and soil. “I have come to the conclusion that people should be made aware of reading these signs and taught how to save their lives,” he said.

(Edited by Smriti Sinha)

Also Read: ‘Bid to capture BMC’ — Why BJP minister’s office at civic body HQ has Oppn up in arms