While my friends were otherwise occupied on Sundays, I hiked to forests such as Bear and Bombay Sholas, revelling in being in the jungle on my own without having to hear the yapping of other kids and the chaperone prodding me along. I searched for snakes, discovered birds’ nests and observed lizards sunning themselves on branches. Under a log, I scooped up my first snake of the hills, and it twisted and writhed in my hand, revealing the bright yellow squiggly markings on its underside. At first I couldn’t tell the shield-tailed snake’s blunt tail from the head or what it ate. At least part of the mystery was solved when I came upon one swallowing an earthworm.

Besides beautiful delicate green vine snakes in the grasslands, other species were scarce in the highlands. The weather was too cold for them, as the school representative had told Mom a few years ago. Absorbed by the sights, sounds and smells of the forest, I had to tear myself away to be back in time for dinner. I couldn’t wait to get into high school to go on overnight camping trips.

On one memorable class trek, we found my first venomous snake, a bright green pit viper lying on the road with its head squashed. I was about to open its mouth to see the fangs.

‘Don’t touch it, Breezy,’ the chaperone said. ‘It may be dead, but it still has poison.’

I dragged myself away from it and trailed behind the group. Within a few metres was a live one coiled on a branch next to a small stream. Its triangular head made it obvious that this was not a harmless vine snake, but a venomous pit viper. The teacher leading the group was too far ahead to stop me from examining it. But I was nervous. What if it bites me? I admired its beautiful green colour and the large overlapping scales on its head and left it alone. I would learn much later that it was the large-scaled green pit viper.

On our way back, the pit viper was still there, immobile in the same place. I pointed it out to the others, but they had a hard time seeing it. Its green colour and sinuous body blended with the mossy tree limb. My friends took a while to see vine snakes too. Years of squinting into bushes had trained my eyes to spot them. Later, I read colour-blind people were better at recognizing shapes, since they had learnt not to depend on colour. Maybe there was something to that.

My Hindi was useless in Kodai as the local people spoke another language, Tamil. Shadrach, the cycle rental man, knew some English, and with his help and hand gestures, I learnt one Tamil phrase at a time. When he heard of my interest in fishing, he invited me to fish with him and his friend, Velu, at the Kodai Lake ten minutes away.

I had brought hooks from Bombay and put together the rest of my fishing rig by buying a long bamboo pole, stripped peacock feathers for floats, and lead weights from my newfound friends. Their choice of bait to catch carp was vadai. Most south Indians know it as a spicy doughnut- shaped snack. But this vadai, an inch-thick, fried dense pancake of lentil and peanut flour mixed with spices, was specially made for fishing bait as it stayed on the hook when tiddlers nibbled. Shadrach swore the smell of the masala enticed the fish.

Without a reel, casting the bait took some manoeuvring. I laid the eight-foot rod on the ground and stretched the full length of the line across the road after making sure no car was in sight. Back at the ‘handle’ end of the pole, I whipped the filament over my head. The bait arched and splashed about twenty feet away from the bank. I aimed for clear water, avoiding the stands of lily pads, but still lost many a hook when the line became tangled.

Resting the rod on a forked support stick, as a bite could take half an hour or more, I baited a smaller pole with a tiny ball of sticky peanut flour paste to pull out tiddlers. The fishermen caught them as a fallback option for dinner, in case big fish were elusive. Since my meals at the dining hall were assured, I didn’t need an alternative. But catching these tiddlers like the older fishermen made me feel as proficient as they were. At the end of each fishing session, Shadrach or Velu took them home.

One Sunday, I sat on the lakeshore, staring at the quivering peacock- feather float. I imagined the little ones nibbling at the bait and attracting the big fellows. A hefty fish surfaced and gulped a swimming insect. That would be a good size to catch. What kind are the big ones? Could they be bottom feeders? In that case, I would be better off without the float. Is the vadai any good? My thoughts came roaring to the present when the peacock feather bounced twice and dunked forcefully under. Something huge had grabbed the bait. I raised the long pole and struck. It didn’t give. Had I hooked a log? Then, with a swirl of water, a large fish surfaced and shook its head, trying to dislodge the hook. Shadrach and Velu, who were smoking beedis and minding their floats, leaned forward to watch. As it tore back and forth, I struggled to keep the line from getting tangled in the lilies. The fish had a lot of fight left and wasn’t coming ashore soon. I grew worried. It might snap the filament or the rod.

Shadrach had once described landing a big carp, and I followed his example. I tossed the bamboo pole into the water and ran to the Kodai Boat Club, which was about five minutes away. A boatman I knew lounged in his skiff, which I requested him for. In my hurry and breathlessness, my words were jumbled. But he understood and helped me untie it. I grabbed the oars and rowed furiously, following Shadrach’s and Velu’s excited gesticulations towards the western side of the lake, where the rod bobbed like a giant fishing float. When I got closer, a large tired mirror carp rose to the surface, mouth gaping from the effort. I picked up the pole and pulled the line until the fish came alongside. I wasn’t afraid to slide my thumb and two fingers into the gills, since carp are toothless, and haul the three-kilogram fish into the boat. It was the biggest one I had ever caught. I stared at its huge, glossy golden scales, my heart pounding with excitement and exertion. Then a strange sadness enveloped me. I grieved killing the fish that had been going about its life underwater. But how can I give up the thrill of the hunt?

The guys on the bank laughed and clapped as I rowed back, exhausted. The boatman pumped my hand. ‘Very good, very good.’ After promising to pay later, I trudged down the road, elated by the fishermen’s enthusiasm about the big carp. What am I to do with the fish now? Since I had no way of cooking my catch at the dorm, I gave it to Shadrach, a gift for teaching me how to fish that lake. I felt a kinship with these men that I didn’t share with any of my classmates.

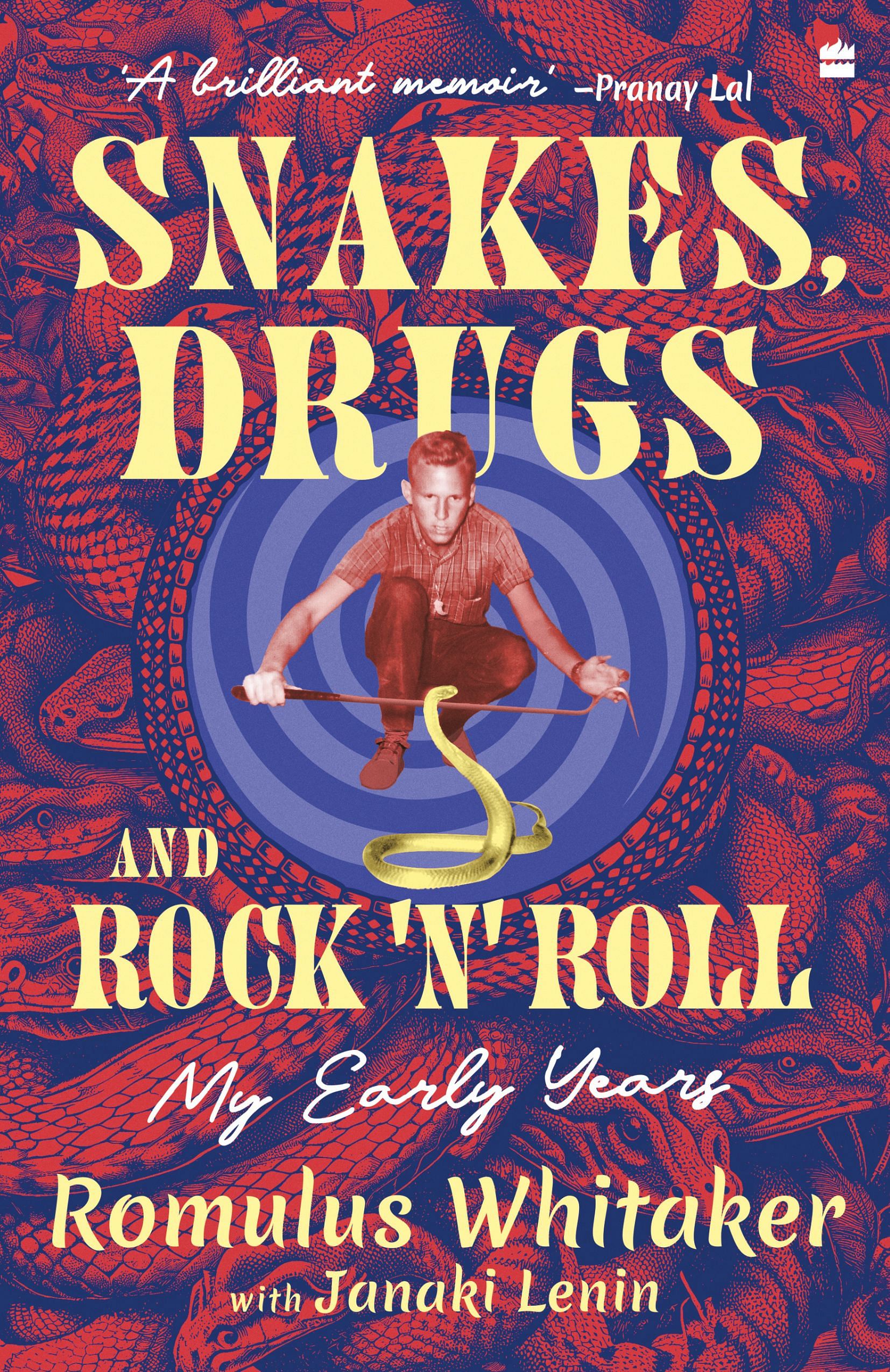

This excerpt from Snakes, Drugs And Rock ’N’ Roll: Confessions of a Snakeman by Romulus Whitaker and Janaki Lenin has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from Snakes, Drugs And Rock ’N’ Roll: Confessions of a Snakeman by Romulus Whitaker and Janaki Lenin has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.