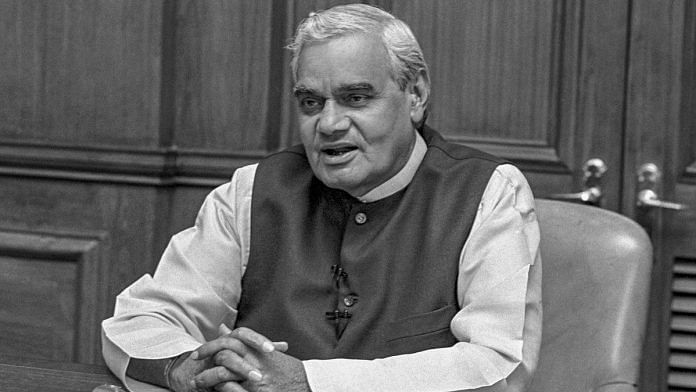

Here is one way you can put the life of Brajesh Mishra in context. If you asked the top leadership of this UPA government to name one person they could inherit from the NDA, the answer was instant: Brajesh Mishra. Obviously, this was not primarily for his strategic (as in security and foreign policy) talent. In that area, the UPA believes it is well-endowed. It was for the way he had perfected the craft of exercising the PMO’s power even in a messy alliance and within the Sangh Parivar. This while giving total cover, and, in that brilliant expression immortalised by the notorious Lt Colonel Oliver North in the Iran-Contra hearings in the US Congress in 1987, plausible deniability to the boss, as Mishra always referred to Vajpayee.

It was helpful, of course, that Vajpayee trusted him probably even more than Narasimha Rao trusted A.N. Verma. Rao would still read the files put up by Verma before signing. Vajpayee usually didn’t. I have had this gem salted away from one lazy early evening in 1999 (the Lahore bus ride and Kargil year). Mishra walked in holding a drink, barefooted and his trouser legs folded two turns so they wouldn’t drag or trip him, and asked if certain files had been signed. Kar diya, jaisa aap ne kaha, said Vajpayee. Kintu dhyanpoorvak dekh ke likha thha na aapne? Kahin kuchh gadbad par hastakshar ho jayein aur kal phir Shekhar ji jail pahuncha dein.

Briefly: Signed as you said I should, but I hope you were careful not to get me into an embarrassing situation. It was typical Vajpayee, pulling the leg of two persons at the same time. But it spoke of the trust between them. Remember how Vajpayee rose to Mishra’s defence when the RSS wanted his head. And Advani, who thought he was an interloper and a busybody and primarily responsible for the rift between the BJP’s top two, and their families, wanted to cut him down to size. Vajpayee said they could take his job instead.

It’s a great pity we do not have Mishra’s memoirs for his Vajpayee years, unless he has left behind something that might surface later. He pioneered a new and hitherto unimaginable line of succession of creative minds with IFS ancestry that were willing to take a fresh look at the post-Cold War world and shift the paradigm he found an ally in Naresh Chandra (though from the IAS). J.N. Dixit and Shivshankar Menon then became worthy foreign service successors in that new, baggage-free worldview.

Also read: My encounters with Vajpayee, a statesman who could smile even in a tough situation

He was never too diplomatic when it came to expressing his impatience with the MEA’s old think. At a very select farewell dinner he had given for US ambassador Robert Blackwill in 2003, he came to my defence as I was being upbraided by two of the three foreign secretaries around the dining table (J.N. Dixit being the exception) over a ‘National Interest’ piece I had written headlined, ‘Indian Fossil Service’, for our foreign services’ unchanging stodginess.

Mishra suddenly interjected to say, One of these days I am going to ask my army chief to send me a regiment of tanks to demolish the MEA, I am so fed up with them.

Listen Brajesh (he pronounced it as Bragesh), if you are a truly great friend, can I request you to lend those tanks to me first because I have to set them on Foggy Bottom, they are much worse, said Blackwill.

It led to a spirited debate on whether the bureaucracy was sinner or scapegoat. Blackwill concluded the argument saying career civil servants were like doctors in the emergency ward of a hospital, trained to follow standard operating procedures as a patient was wheeled in at night. It was then for the specialists, the politicians in this case, to come the next morning and take a substantive call on the treatment.

Mishra helped Vajpayee and Jaswant Singh demolish the old Holy National Consensus on strategic and foreign policies. It ranged from an unabashed strategic partnership with America, the tightest embrace of Israel, the burial of the old Atom for Peace-type nuclear ambiguity and hypocrisy, to a qualitatively new engagement with Pakistan. He started the quiet mothballing of the old Nehru-Indira strategic doctrine.

He built new lines of communication with the Pakistani establishment. These were robust enough to survive two-and-a-half war-like situations: Kargil, Op Parakram and the IC-814 hijack. They probably helped avert escalation at more than one juncture, and you wish he had told us that story himself.

For a career diplomat, Mishra was a risk-taker. He pushed it a bit sometimes, to the extent that you would describe as strategic brinkmanship. The nuclear tests of 1998 were a remarkably bold gamble. Mishra believed it culminated in the India-US nuclear deal and the ending of India’s nuclear apartheid. He saw Manmohan Singh’s success with the deal as a logical, and patriotic, conclusion of a project he had launched exactly a decade earlier. That is why he broke ranks with the BJP to support it.

He loved playing dangerous games. I became witness to two. At the peak of the Kargil war, our newsroom called me around midnight to flag an odd-sounding PTI story datelined Kochi. It said the western and eastern fleets that is, almost the entire navy had sailed into the Arabian Sea to move towards Pakistan, in case Kargil escalated. It seemed silly that such information would be released to PTI and we thought it would be more stupid to publish it and alert the Pakistanis. But, curious, I gathered the courage to call Mishra.

Khabar aayi hai PTI se to phir chhapiye aap. Zara prominently chhapna, front page pe, he said.

Kya baat kar rahe hain, Brajesh ji, I said, Is this the return of some Horatio Nelson era that armadas sail into battle after public ceremonies and band performances?

But why are you so worried, bhai? It is the PTI’s story not yours. Chhapna… prominently…

I now figured this was a high-level plant to increase pressure on the Pakistanis and the international community. Of course, I thought it was silly and argued with him on it several times later. Of course, he insisted journalists would never understand high strategy or diplomatic tactics. Of course, indeed, we did not follow his advice on publishing that story.

The second was during the equally tense, war-like period of Op Parakram. We all know something spooked the Americans in the summer of 2002 and Donald Rumsfeld came flying to India all of a sudden, on June 11. My American sources told me much later they were rattled as their satellites picked up the movement of certain IAF assets into a profile that meant escalation. I asked Mishra several times what exactly had happened. He confirmed that some key IAF assets had been moved. What if it panicked the Pakistanis into believing a war was beginning? Wouldn’t things have spun out of control? He said that may indeed have happened, though that was not our intention. Were we, then, playing a game to spook everybody? He didn’t answer that, but I have always presumed we were.

He loved negotiation and conflict-resolution. But coercive diplomacy was the essential feature of his strategic style, with such risky bluff and brinkmanship thrown in. Of course, I rarely saw him ruffled. Not even on a summer afternoon in 2002 when it looked like war would break out any moment after families of Indian soldiers were killed in the massacre at the Kaluchak cantonment (May 14, 2002) near Jammu, and he was reported to have had a tough, long phone conversation with Condoleezza Rice the previous night. I found him in his office, relaxed, more like chilled, as you’d say now in computer English, drowned in swirls of smoke as usual.

Kya baat huyi aapki raat ko, I asked.

Aap Condi ki baat kar rahe hain? I told her, dekhiye, now we cannot hold on, we have to take some action. She was protesting it would upset their own operations in the Af-Pak region, he said.

So what did you say, I asked, also alarmed that maybe now a war was imminent.

Maine kaha, woh dekhiye, aap wahan jo kar rahe hain, karte rahiye, hum yahan apne aas-paas jahan camps vagerah hain, apni karyavahi shuru karte hain, he said.

He tried saying it with the stern demeanour of somebody going to war, but I caught a flash of mischief on his face.

So you are playing the same dangerous game again? I asked.

And then he gave me his central, intellectual underpinning of coercive diplomacy. What are we doing here? We are using the threat of war. It can only work if it is so real even we start believing it.

He played that game, mostly successfully, and thereby defied the age-old Indian doctrine of wait-watch-react passivity.

But if he showed one failure, it was in not knowing when to declare victory in that long standoff and bring his forces home. I believe he should have done it as early as January 12 (2002) when Musharraf made his grovelling speech, even stating that Pakistan had not given asylum to any of our terror suspects that we were asking him to turn over.

Also read: The life and times of Atal Bihari Vajpayee

There was, however, one time when I saw him ruffled. And let me make a clean breast of it, even if it concerned The Indian Express. This was when the paper had carried a series of exposes embarrassing the Vajpayee government: the petrol pump scam, the scam on allotment of institutional lands to Sangh Parivar front organisations, and the Satyendra Dubey (the IIT engineer murdered while working for the NHAI by the mafia in Bihar) case. A top official in the State Bank of India, for decades this company’s bankers, told me with a great deal of surprise and dismay that he had got a call from somebody in the PMO to give the Express trouble. He said when he told the person the Express Group had impeccably clean accounts he was asked if he could somehow still give it grief. The banker was an old Express reader, loved the paper, and was aghast.

I sought time with Vajpayee, and the tea had just been served when I said to him, Suna hai, aajkal aap ne PMO se dadagiri shuru kar di hai. I told him the story. And I must say Vajpayee looked genuinely shocked and swore he had not given any such instructions.

Next day I was invited to Mishra’s office. Arrey bhai, aisi baat thi toh… why didn’t you tell me first? Where was the need to go to boss? He has never pulled me up like this, and I am not used to it, he said, now more rattled than annoyed. He promised that it was all freelance activity by a Sangh Parivar busybody who hung around in the PMO, misusing people’s phones, and that the mischief had been nipped.

The story had a happier ending. In fact, I got another apology from a very senior officer who had made that call to SBI and he said he wouldn’t believe he had been forgiven until I attended his child’s wedding later that week. I did go for the wedding at the banquet lawns of Khel Gaon (Asian Games Village) in South Delhi. It was a genuine Hindi heartland wedding with hundreds of guests, mostly from the officer’s native Uttar Pradesh. Sure enough, I was drawing more attention than I normally would from a central UP baraat. It was only later that evening that I discovered many innocent baraatis had mistaken me for fellow editor, and Hindi news TV star, Prabhu Chawla.

Also read: How Congress leader Salman Khurshid had to ‘pay a price’ for a hug from Vajpaye