Bengaluru: Earth and its seven Solar System siblings may have a distant (really distant) cousin outside the Milky Way, but it could be decades before we know for sure.

Astronomers have detected the signs of a planet outside the Milky Way galaxy through NASA’s orbiting Chandra X-ray observatory. If confirmed as a planet, this body will be the very first extragalactic exoplanet (exoplanet is a planet outside the solar system) to be observed.

It holds the potential to open up a whole new arena of extragalactic exoplanetary, with X-ray telescopes allowing us to detect stars, and now planetary systems, at vast distances.

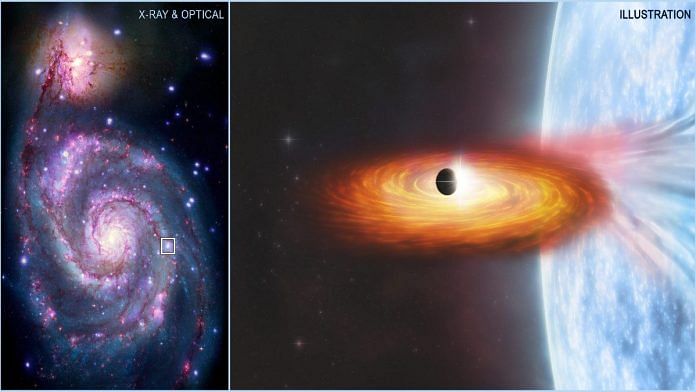

The potential planet is located 28 million light years away, in the Messier 51 (M51) galaxy. It is thought to be the size of Saturn, orbiting its host — a neutron star or a black hole — at a distance twice that of Saturn’s from the Sun (1.4 billion kilometres).

The findings were made by a collaboration of researchers from the US, Canada, China, and Australia, and the authors have proposed the descriptor “extroplanet” for an extragalactic exoplanet.

The study was published in the journal Nature Astronomy this week.

Also Read: NASA’s latest exoplanet discovery could help explain how planets evolve

Detection and analysis

The astronomers involved in the discovery made the detection through the transit method, where a dip in the luminosity of a star — as viewed from Earth — is observed when a planet passes in front of it.

The Chandra telescope performed this observation in the X-ray wavelength, noting a large, three-year-long dip in X-rays coming from the host star.

Chandra — named for physicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, who deduced the maximum mass of stars that collapse into white dwarfs — has previously detected exoplanets using the same technique within the Milky Way.

After much analysis, the team ruled out alternative explanations for the X-ray dip, including other transiting objects or fluctuations caused by dust and gases.

The research started out specifically looking for planets around X-ray binary stars, which are two stars undergoing mass transfer. The more massive star in an X-ray binary feeds on the less massive one, sucking its matter in.

The massive star is a compact object, usually a neutron star or a black hole (both results of a star exploding), capable of feeding on a star. As matter from the star nears the compact object, it starts to glow hot and release energy in the form of X-rays.

Since some of the earliest exoplanets ever detected were orbiting fast spinning pulsars, which are born from X-ray binaries, the authors theorised that these systems could also hold potential planets.

The more massive object in this binary is M51-ULS.

Being a mass-transfer binary, the object, which is either a neutron star or a black hole — two of the densest objects in the universe — is one of the brightest X-ray emitters. It is categorised as an Ultraluminous Supersoft Source (ULS).

The less-massive-but-larger-sized object is an orbiting companion star that is 20 times the mass of the Sun, and is losing mass to the compact object (as seen in the illustration in the lead image).

‘Extroplanet M51-ULS-1’

The extroplanet candidate is named M51-ULS-1. The planet’s size has been deduced from its physical transit in front of the compact object, which blocked out X-rays completely for three hours.

The extroplanet is thought to be orbiting at a distance that is twice that of Saturn’s orbit, which also fits the expected distance that a planet should be in order to survive a violent supernova, during which its host star became a neutron star or a black hole.

The candidate needs to be confirmed as a planet, but its orbital period and distance from Earth means the body will transit once again only after 70 years.

“Unfortunately to confirm that we’re seeing a planet we would likely have to wait decades to see another transit,” co-author Nia Imara of the University of California at Santa Cruz was quoted as saying in a NASA release. “And because of the uncertainties about how long it takes to orbit, we wouldn’t know exactly when to look.”

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: NASA telescope finds exoplanet trio that can unravel mysteries of planet formation