Bengaluru: Researchers have discovered that apart from some antibiotics, non-antibiotic drugs like antidepressants — that help treat depression and anxiety — could also be a potential driver of drug resistance in bacteria. The researchers, however, say that the findings are no reason for people to stop taking antidepressants.

Growing antibiotic resistance, where bacteria become resistant to the drugs used to treat them, is a big concern among medical experts and is considered a major threat to public health.

According to a study published in the Lancet, a peer-reviewed medical journal, globally about 1·27 million people had died due to bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019.

Working on bacteria grown in the laboratory, Australian scientists realised that after “a few days” of exposure to antidepressants, bacteria develop resistance to a variety of antibiotics.

The findings were published in the peer-reviewed journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) on 23 January.

Also Read: Livin’ la vida virovore — scientists find 1st microscopic organism that feasts on viruses

Non-antibiotic drugs & antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria are able to withstand the effect of antibiotics. Such bacteria are now often referred to as ‘superbugs’.

The resistance occurs naturally and makes these bacteria harder to treat when they infect humans or other animals, subsequently resulting in increased mortality, higher medical costs, and further consumption of medication cocktails.

The problem is thought to be occurring all over the world, and leading to common diseases like tuberculosis, pneumonia, gonorrhoea, etc becoming harder to treat as the standard antibiotic drugs become less effective.

In the past few years, many scientists suspected that non-antibiotic drugs are fuelling antibiotic resistance by affecting bacteria in the body. A common suspect was antidepressants, which are known to trigger an immune response in some bacteria.

According to medical journal Nature, the senior researcher and last author on the paper, Jianhua Guo, became interested in non-antibiotics driving antibiotic resistance nine years ago, when a study by his laboratory (University of Queensland) found more antibiotic-resistant genes in wastewater samples obtained from residential areas than from hospital wastewater samples, where antibiotic use is higher.

He and other teams around the world were also simultaneously observing that antidepressants were able to slow and stop the growth of some bacteria.

This work led to a paper in 2018 which showed that fluoxetine, an antidepressant commonly known under the brand name Prozac, could lead to E. coli becoming resistant to multiple antibiotics.

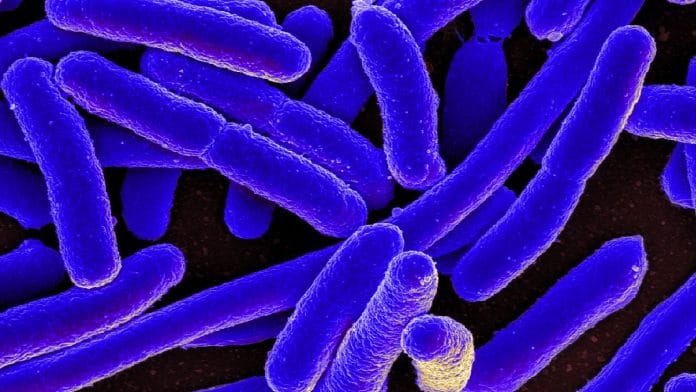

E. coli is a bacteria mainly found inside large intestines of humans.

Building on the 2018 work, Guo and his team studied five other antidepressants in the latest study and studied how E. coli became resistant to 13 different antibiotics.

In experiments, the team noticed that in well-oxygenated environments, the antidepressants caused the production of molecules toxic to bacteria, which then triggered its defence mechanisms. This caused the activation of the pumping system within bacteria, which it uses to expel foreign molecules out. While bacteria reacted to toxic oxygen molecules, it also started to expel antibiotic molecules, preventing the drugs from destroying the microbe.

This is thought to explain how bacteria withstand antibiotics even without genes to specifically resist a certain class of drugs.

Additionally, the bacteria exposed to antidepressants had an increased chance of mutation, thus leading to further development of drug-resistant genes.

Notably, E. coli is more anaerobic (without oxygen) than aerobic. The group also found that antibiotic resistance developed slower in anaerobic conditions. Thus, development of antibiotic resistance within human bodies due to antidepressants might be slower, but could happen with prolonged use.

Lastly, the group also found that a continued exposure to antidepressants like sertraline led to transfer of genes between different bacteria, which resulted in the spread of resistance through a population of microbes including among different species of bacteria.

These findings are now being followed up with studies in conditions similar to the human body, within which these bacteria are treated. The team is now studying the microbiome of mice that are being administered antidepressants to understand how the process occurs within the bodies of animals and humans.

(Edited by Anumeha Saxena)

Also Read: New US-approved gene therapy for Haemophilia B world’s most expensive drug — $3.5 mn per dose