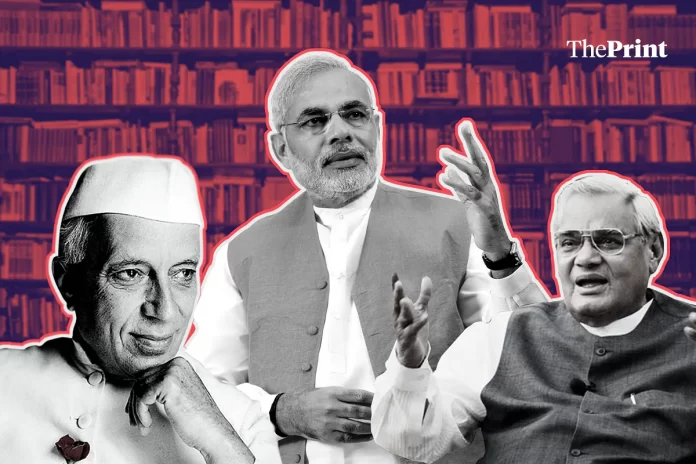

New Delhi: Concentration of power and promotion of “Nehru family patrimony” at the party’s cost by Indira Gandhi, corruption scandals such as the Bofors during Rajiv’s time, “worsened inequality” after the 1991 economic reforms along with the “saffron wave” led to the decline of the Congress, says the Harvard Business School (HBS) paper that was quoted by PM Narendra Modi in the Lok Sabha Wednesday.

The study published in 2016, however, lauds India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who has long been attacked by Modi and his BJP colleagues.

Modi brought up the paper while replying to the Motion of Thanks on the President’s Address. Attacking the opposition, he said, “some people here have a craze for Harvard studies”, adding that “over the years an important study has been done at Harvard and the subject of the study is the ‘rise and fall of India’s Congress party’.”

He was taking a veiled dig at Rahul Gandhi, who had a day earlier brought up in Parliament the findings of the Hindenburg report, and said the meteoric rise in Gautam Adani’s fortunes happened after the BJP came to power in 2014. The Congress MP had also said the relationship between politics and business should be a case study by business schools such as Harvard.

The study in focus was was authored by Akshay Mangla, an Associate Professor in International Business at Oxford University’s Said Business School (who was then working with HBS) along with Jonathan Schlefer, a researcher at Harvard Business School.

Titled ‘In the Name of Democracy? The Rise and Decline of India’s Congress Party’, the 30-page paper examined the political history of the Congress and its evolution since Independence, looking into the factors that led to the party’s initial rise to power, its dominance in Indian politics, and the reasons behind its decline.

Concluding the paper, the authors mentioned how the late former PM and BJP leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee was fond of Nehru and compared him to Lord Ram when he died.

The study quoted an anecdote about Vajpayee wanting a portrait of Nehru on his wall when he became a minister. “It is held that upon entering his new office as external affairs minister in 1977, Vajpayee saw a blank wall. He then turned and looked at his secretary and said — ‘this is where Panditji’s portrait used to be. I remember it from my earlier visits to the room. Where has it gone? I want it back’,” the authors said.

From Nehru’s Congress to being ideologically flexible, to Indira Gandhi’s Emergency (1975 to 1977) to the party’s pro-business turn — the paper captures it all.

However, there is no mention of the Congress in the post-Vajpayee era and the 2014 elections.

Also Read: Poetry, storytelling & Harvard study — how Modi laid into Congress, Rahul Gandhi in LS speech

Nehru era after Independence

Acknowledging the Congress’ efforts to lead the freedom movement, the paper elaborated on how the party had enormous political support after Independence, and how, during the Nehru era, his embrace of secularism and rule of law served as an example for others in the party.

“Nehru showed deference to Parliament. He meticulously respected court rulings, even when they struck down his cherished policies, such as land reform. The Supreme Court and the Election Commission, which supervised elections, enjoyed independence from politics, Nehru adopted a foreign policy of ‘non-alignment’ during the Cold War. He limited defense spending, preserving public resources for economic development,” the study noted.

Explaining the Congress’ internal decision-making processes, the paper said a “managerial class” at the top of the party made decisions via consensus. Below it, “an elaborate network of factions” engaged in intense competition.

Intra-party democracy allowed for alternation in leadership. Party members who rose up the ranks challenged those at the top. At times, they broke off to organise external opposition, it added.

In 1959, Nehru’s daughter Indira was elected as president of the Congress. Five years later, Nehru passed away.

According to the authors, during her years of tenure, Indira bypassed state-level party organisations which were earlier consulted in the selection of electoral candidates, (and) “consulted a small clique of advisers consisting mostly of personal ties, including her son Sanjay Gandhi”.

“Congress party’s norms of consultation deteriorated. The organisation behind ‘a great national movement’ had become converted into a Nehru family patrimony. Where Nehru stressed neutrality and autonomy of bureaucrats, Indira rewarded some for personal loyalty and punished those who lacked it,” the paper said.

End of Congress system

Commenting on Indira Gandhi’s regime, the paper said that after winning with a two-thirds majority in the 1971 elections, she began “plebiscitary politics”, appealing directly to voters, during which she “sidelined” party workers and “solicited funds from interested or intimidated sources”.

The paper also noted that Congress’ land reform measures to redistribute large holdings and provide tenant farmers security were “poorly implemented in practice”, generating massive inequalities in land ownership.

“The failure of the land reforms weighed on the rural economy,” it said.

According to the paper, the Gandhi family’s concentration of power led to party splits and defections from state-level ranks. “Party leaders in Delhi became out of touch with rural voters. The locus of power was shifting to state governments, whose control over policy implementation would only grow. The era of the Congress ‘system’ had passed,” the paper observed.

On the leadership of the party, it said: “The first generation of leaders had sacrificed their careers and faced jail in the independence movement. A new generation of politicians arose in the 1960s who sought power and wealth from office. Many began to use public resources for personal gain, collecting ‘black money’ to fund their electoral campaigns.”

In 1980, after Emergency and Licence Permit Raj, when the Congress came to power again, Indira Gandhi “abandoned her socialist rhetoric and promised to stabilise the country”. She took a pro-business turn, said the paper, and also started courting the support of a Hindu majority, paying deference to temples and priests.

Liberalisation

After Indira Gandhi was assassinated in 1984, her son Rajiv Gandhi “strengthened the state’s pro-business leanings, reduced corporate taxes and tried to promote exports”.

“To some observers, these changes did not signal a paradigm shift in economic policy. They did little to reduce import barriers, liberalise capital flows, or sell unprofitable public enterprises. Yet, the results were dramatic. Where growth averaged 3 per cent in the 1970s, it nearly doubled to 5.9 per cent in the next decade,” the paper said, adding that the Congress’ pro-business tilt left the demands of the rural poor unaddressed.

At the same time, regional parties representing the marginalised were on the rise and were gaining national prominence, the paper pointed out.

BJP, the formidable rival

With the 1991 reforms came strong economic performance but also worsening unequal and nearly stagnant growth in manufacturing jobs, the paper stated.

Alongside India’s gradual economic opening, a political movement took shape under the “saffron wave” and “the BJP doubled its vote share” in the 1991 general elections after the 1990 Rath Yatra by veteran leader L.K. Advani.

“The BJP proved a formidable rival, ending Congress domination of elections. The Congress had also changed, recording major setbacks, including a corruption scandal stemming from a $285 million contract awarded to a Swedish arms dealer, Bofors,” the paper highlighted.

Praising the polity reforms and initiatives by the Vajpayee government (1998 onwards), the paper said that under his leadership, the country clocked an “annual growth rate of 7 per cent by 2000”.

“Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee was making headway with economic reforms and social policies like Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, a programme for universal primary education. The world had caught wind of India’s progress. In March 2000, President Bill Clinton paid a state visit to India, the first by a US president in 22 years,” said the paper.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Is Modi a better builder of India or Nehru? They aren’t all that different