Thackeray rode on his anti-outsider rhetoric, pandering to a sense of alienation among Maharashtrians, changing Mumbai’s landscape forever.

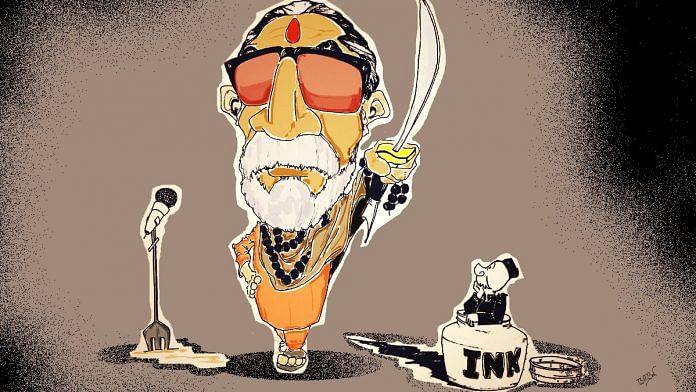

New Delhi: The image of this political firebrand was unmistakable.

With thick-lensed glasses and a trademark beaded necklace, Bal Thackeray was the original flag bearer of Marathi chauvinism. But much before he took centre-stage in Maharashtra politics, Thackeray was a cartoonist with a cause.

On his death anniversary, ThePrint looks back at his life.

Early professional life and Marmik

Born on 23 January 1926, Thackeray began his career as a political cartoonist with the Free Press Journal. Thackeray wielded his cartoons as a political weapon but was forced to water down his critical commentary. Thoroughly frustrated, he quit in 1960 and started his own political weekly, Marmik.

Thackeray vehemently criticised Left-aligned politicians in his columns. The columns also allowed him the platform to express his ‘anti-outsider’ hate-filled rhetoric that came to define his politics. Time and again, he urged the Marathi Manoos or the Marathi common man from “bending down” before ‘outsiders’ – his targets shifting from South Indians, Muslims to North Indians.

Thackeray created Kakaji, a character constant in most of his cartoons, to embody the so-called angst of the Marathi Manoos. In some cartoons, Kakaji would be begging in the streets, in others he was being thrashed by political powers of the time.

By this time, Marmik had garnered a significant fan base among Maharashtra’s middle-class.

It was in the mid-60s that Thackeray first began pandering to a sense of alienation that had crept into the Maharashtrian psyche. He published lists of corporate workers employed in Mumbai, then Bombay, highlighting how many of them were “outsiders”, South Indians to be specific.

It sparked an avalanche of letters to the Marmik office, with many sharing their own experiences of being “pushed out” by non-Maharashtrians. It solidified Thackeray’s pro-Maharashtra slogan that later amplified into a louder pro-Hindu and anti-Muslim voice.

Also read: I asked Balasaheb Thackeray, “Are you a mafioso?” — and lived to tell the tale

Shiv Sena and Saamana

In 1966, Thackeray abandoned his long-standing aversion to party politics and formed the right-wing, nativist political outfit, the Shiv Sena.

Thackeray and Shiv Sena drew their inspiration from Shivaji, a 17th-century king of the Maratha kingdom. Saamana was launched as the party’s mouthpiece. Thackeray kept adding his humorous touch to the socio-political problems of his time; however, cartooning took a backseat as the Shiv Sena chief got involved in full-time politics.

Thackeray set the tone for his politics, saying he wanted a ‘respectable’ place for Maharashtrians in Mumbai’s political and professional landscape. Declaring himself as the pramukh (chief) of the Shiv Shena, he employed military metaphors and slogans advocating muscle power to mobilise his followers. Violence and intimidation were Thackeray’s weapons to make enemies toe the line.

In 1970, Krishna Desai, a popular trade union leader was stabbed to death, allegedly by members of the Shiv Sena. The murder made front page news and was followed by swift arrests. In all, 16 people, all from the Shiv Sena were charged and convicted.

The Desai murder signalled a far-reaching transformation in the city of Mumbai. It set a template for the Shiv Sena’s activities over the years. From wrecking movie theatres that screened Tamil films to allegedly murdering Communist Party leaders, the Shiv Sena had done it all with Thackeray at the helm.

He attracted significant attention to himself and his party by evocatively expressing his admiration for Hitler. In 1993, he gave an interview to Time magazine. “There is nothing wrong,” he said, “if Indian Muslims are treated as Jews were in Nazi Germany.” He incited violence against Muslims and took strong stances on several aspects of popular culture such as the celebration of Valentine’s Day.

Populist politics

In spite of spreading hatred and violence, at the heart of Thackeray’s propaganda was a populist ideology. His cartoons in the Free Press Journal and Marmik depicting Kakaji, the Marathi common man were perhaps the first glimpses of his populism.

Thackeray’s populism though came at a cost. His argument was that in order to achieve people’s welfare, the institutions of liberal democracy had to be rigged.

Neither a socio-economic tragedy nor a cultural compulsion sufficiently explains the emergence of Marathi Manoos. It was all a result of Thackeray’s populist politics.

Bombay is Mumbai now. Six years since Bal Thackeray’s demise, political parties including the Congress and BJP have tamely adjusted with the Sena ideology. The lasting legacy of this iconic leader was perhaps more in his populist politics than in his regional chauvinism.

Held the “ remote “ over his party’s government in Mantralaya between 1995 and 1999.