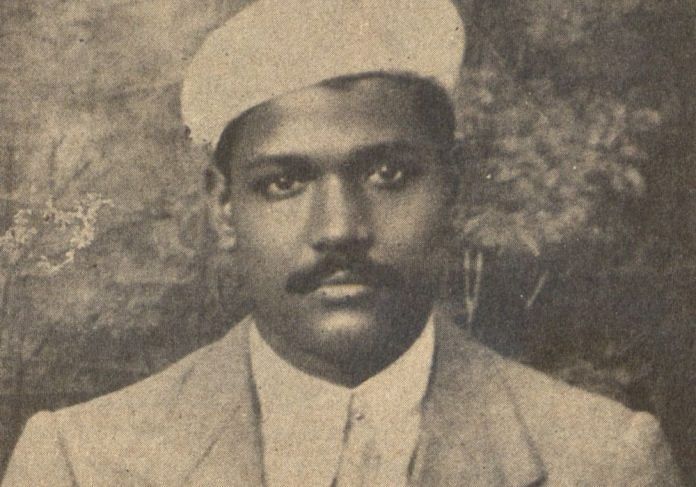

Remembering Ramnath Goenka, who remains a towering presence on Indian journalism 27 years after his death.

New Delhi: In the early 1920s, a man on the brink of adulthood arrived in the city of Madras with spare change in his pocket.

A native of Darbhanga, Bihar, he had been sent there to learn the tricks of the jute and yarn trade. Instead, the teenager chose to deliver newspapers for a living, working as a dispatch vendor for the Free Press Journal.

He probably didn’t realise at the time that he would one day stand at the helm of one of India’s most prestigious and trustworthy media empires.

Born on 3 April 1904, Ramnath Goenka is considered the founder of The Indian Express as we know it today. Friday marks the 27th death anniversary of Goenka, who died on 5 October 1991 after a prolonged battle with illness.

By the age of 30, Goenka had managed to save enough money to buy shares in The Indian Express at an auction on Mount Road, Chennai. Back in 1934, it was an ailing English newspaper, founded under the leadership of Chennai-based P. Varadarajulu Naidu two years before but sold to S. Sadanand of the Free Press Journal soon after.

In 1936, Goenka bought a majority stake in Express from Sadanand, taking full control of the paper.

Also read: Kuldip Nayar: The rock star Reporter who should’ve been Editor

Goenka, ‘the hard taskmaster’

But that’s not all Goenka bought at a Murray and Company auction.

Around the same time, at another auction hall in Mandaveli, Goenka witnessed Subbaraya Aiyer, the founder secretary of Vidya Mandir School, try and squeeze himself into a child’s rocking chair.

The sight of the tall, big-built Aiyer attempting such a feat reportedly amused Goenka so much that he placed a bid on the piece of furniture.

Goenka then reportedly delivered the chair to Aiyar’s house with a note: “This chair suits you and I hope you enjoy it.”

The story of The Indian Express is as much about the newspaper as Goenka, described by former employees as “a hard taskmaster with the administrative staff… who left his correspondents alone”.

Journalist Coomi Kapoor wrote in her book The Emergency: A Personal History that he “used to claim proudly that he was the first reader of his newspapers, getting up at four in the morning to go through each of his publications”.

“He did not interfere in the stories except on very rare occasions. He allowed us enormous leeway,” wrote Kapoor, a contributing editor with The Indian Express. “It was his editors who bore the brunt of his occasional temper tantrums.”

After taking charge of The Indian Express in 1936, Goenka singularly focused all his energy on expanding the reach and credibility of the newspaper.

Under his leadership, the Express became an umbrella organisation, acquiring several regional publications, including the Dinamani, the Andhra Prabha and the Kannada Prabha.

He set an anti-establishment tone for the paper from very early on — positioning his media house against the British Raj before Independence.

Goenka also participated in the freedom movement. When the British issued a gag order on the press after Mahatma Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement in 1942, he ordered the closure of Express as a form of protest.

According to Kapoor’s book, Goenka wrote in a “farewell” editorial titled ‘Heart Strings and Purse Strings’, “The hard fact of the situation is that if we went on publishing, The Indian Express may be called a paper, but cannot be called a newspaper.”

This battle between the heart and the purse would form the foundation of his struggle over 30 years later.

In 1941, Goenka was elected president of the National Newspaper Editors’ Conference. After India’s Independence, he was nominated to the Constituent Assembly, and “put his signature on the Constitution of India”, according to his official biography on The Indian Express website.

Also read: Elections on its mind, Modi govt won’t give accreditation to web journalists anytime soon

The silver lining in the Emergency cloud

The darkest period of Independent India’s history is also regarded as the golden time of The Indian Express. For, in the face of extreme pressure and censorship, Goenka’s paper was one of the few that did not bend to political will.

By the time the Emergency was imposed in 1975, the Express had a loyal readership base of over 50 lakh people.

On 28 June, three days after the Emergency was declared, The Indian Express resumed publication with an apology for being out of circulation. They also reported the overnight clampdown on the press, the simultaneous raids on media houses, and the cutting of electricity supply to Bahadurshah Zafar Marg, known in the industry as ‘press lane’.

But what remains the most striking form of journalistic pushback was the paper’s historic blank editorial page — a powerful sign of protest against the silencing of the press by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

The government, however, moved quickly against the challenge. Finance minister C. Subramanian reportedly more than suggested that Goenka sell control of his paper to the Congress. When he refused, electricity was cut, loans were barred, a tax demand of Rs 4 crore was mentioned, and Goenka’s son Bhagwan Das was threatened with imprisonment.

Also read: Yes, Indira’s Emergency was a shame, Mr Jaitley, but invoking Adolf Hitler is facetious

The board of directors was said to have been pressured to include government nominees, and while Goenka conceded to this demand in 1975, the fight did not get any easier.

To cripple the newspaper, the political administration even withdrew all PSU and official government advertisements, pressuring private sector companies to do the same. They said Goenka was not adequately listening to the board.

In 1976, as per Kapoor’s account, Goenka suffered a heart attack. Through it all, including some 320 prosecutions launched against Goenka all over India by the authorities, the man did not relent.

“At one stage his lawyer Fali Nariman threw up his hands: ‘Ramnathji, enough is enough. We don’t know how long this damn thing will go on, why don’t you compromise?””wrote Kapoor.

“Compromise, Nariman? We will fight,” he (Goenka) insisted.”

While censorship rules were still officially in place in 1977, The Indian Express published a series of scoops on the evils of the Emergency — forced sterilisation, political prisoners, systematic censorship of the press, land grab, and violation of constitutional rights.

Kuldip Nayar, then an editor at the Express, even broke the story that the government may declare general elections in March 1977 and pull back on certain Emergency regulations.

It was, and is, considered to be the Express’ and Goenka’s defining moment.

“I had two options: To listen to the dictates of my heart or my purse. I chose to listen to my heart,” Goenka is reported to have said when asked about his fight for the truth in the face of immense resistance.

Whatever happened to “Indian Express”, Shekhar Guptas…..Ramnath Goenka must be rolling in his grave.

Way back in 1984 Sh. Ram Nath Goenka wrote, “I can not agree more with the spirit of the action initiated by Mr Anil Maheshwari. In my view, the misuse of a benevolent fund for objects which have no relation to it can be legally questioned.

“But, the law has its limitations. What we must insist on is self-regulation. Those Journalists who accept largesse from the Government must be identified and their names published as the recipient of the benefit. This will blunt their credibility. This in my view, is sufficient to prevent them from playing any mischievous role under the guise of an impartial journalist. We must, therefore, be careful enough to identify and expose only those who are the ‘chosen ones’ for a special favour. We should use our discretion and judgement in each case.

“I do not doubt that the instance complained in the Writ-Petition is downright favouritism the receipt of which is a mark of shame for any journalist. The main issue in my view is not the legality, but the legitimacy of it. The conferment of receipt of such benefit may be legal, yet it will be illegitimate.” He was reacting to a writ petition filed in the Allahabad High Court against the decision of U.P. Chief Minister V.P. Singh to dole out Rs. 25,000 each to five journalists on a visit to the then Eastern European countries. Opinions from distinguished citizens and editors had been sought by the petitioner. You name the editor. None responded or reacted to such blatant misuse of the state coffers.

In a democracy, the need for Journalism of Courage and tall men like Seth Ramnath Goenka never abates.