Tuesday’s results may not be a reflection of Rahul Gandhi’s popularity, but he may have vindicated himself as the Congress president.

New Delhi: Congressmen got a spring in their step Tuesday as the party looked set to snatch two states — Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh — from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and was leading in Madhya Pradesh.

The resurgence of the Congress in assembly polls has got analysts speculating about possibilities in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections even though electoral verdict in these states are not known to reflect any trend for the Lok Sabha elections, except in 2014.

The Congress won Madhya Pradesh (Chhattisgarh was part of it then), Delhi and Rajasthan in November 1998 elections but lost the Lok Sabha elections next year. The BJP won Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan in 2003 assembly elections but lost the Lok Sabha elections in 2004. In 2008, the BJP won Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh but lost in the 2009 general elections.

The exception, however, was the BJP win in 2013 assembly elections in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, which the party followed up with victory in the Lok Sabha elections.

So Tuesday’s results in these states can’t be used to extrapolate anything for 2019, except the fact that the Congress could now hope to improve its current tally of 4 out of 65 Lok Sabha seats in these states in the next general elections.

The general elections would be a different ball game in which the difference between the victor and the loser is likely to be largely determined by how the two principal players perform — Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Congress president Rahul Gandhi.

In this context, these assembly election results indicate a change in their usual form.

Also read: Rahul Gandhi’s discovery of his inner Brahmin is smart and audacious politics

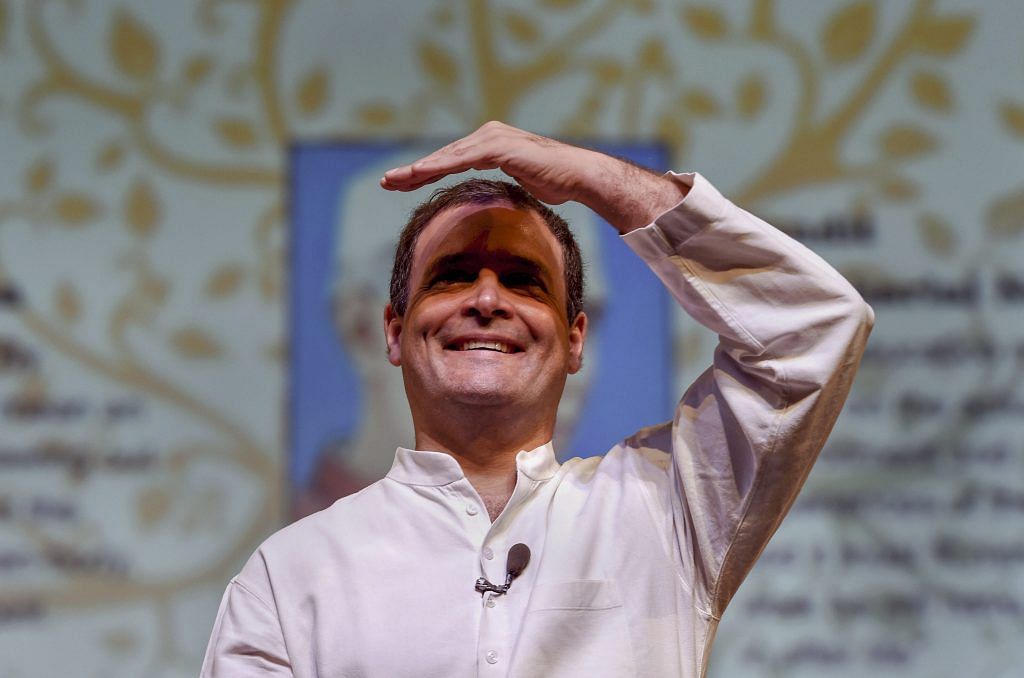

Rahul Gandhi redeems himself

Exactly a year after his election as Congress president, on 11 December 2017, Gandhi seems to have redeemed himself to an extent, securing the first victory over the BJP in a direct contest in an assembly election in five years.

The Congress won Punjab last year, but the Shiromani Akali Dal led the coalition with the BJP as an alliance partner.

Although the Congress’ superior show in BJP-ruled states could be largely attributed to anti-incumbency, it doesn’t take away the from fact that Gandhi was able to galvanise the organisation.

His gambit to re-invent himself as a Dattatreya Brahmin and play soft Hindutva card on the campaign trail and in manifestos was bold and rather audacious. And it paid off.

It also showed a new trait of his leadership — the willingness to take risks. Not yielding to Mayawati’s demand for a large number of seats in Chhattisgarh was one of them. His detractors may find fault in it by pointing out the Madhya Pradesh results where the party seemed to be just falling short of the majority mark, but the gambit paid off in Chhattisgarh. The BSP’s declaration not to support the BJP in MP or elsewhere may come as a vindication of Gandhi’s stand.

In the absence of chief ministerial candidates, he led the charge from the front and dominated the electoral discourse. He was able to curb the internecine fights as the party put up a united show even in faction-ridden Madhya Pradesh where Digvijaya Singh, Kamal Nath and Jyotiraditya Scindia buried their differences to work for the party’s interests.

He was also able to gear up the organisational machinery, with the party putting up a fight in every booth in these states. From selecting party candidates to manifesto preparation and even the training of booth-level workers, he was pro-active.

Tuesday’s result is not a reflection of Gandhi’s popularity though. He may have vindicated himself as the Congress president but has a long way to go as Modi’s challenger for the top post in 2019.

Also, the party’s dismal show in Telangana shows his failure to revive the party in a state that was the Congress’ fort until five years ago.

Also read: Modi factor not good enough to win state elections for BJP anymore

Modi’s ego bruised but national stature intact

The assembly election results exposed the limitations of ‘Modi wave’. Built on the narrative of hope and aspiration, it looked unstoppable for five years as the BJP went on to vanquish ruling parties in one state after another. This narrative, however, seemed to be losing its lustre and appeal when it came to overriding anti-incumbency against BJP governments.

In the states the BJP snatched from opposition parties in the past five years, the common refrain of voters used to be: “BJP ka CM koi bhi ho, Modiji sab theek kar denge (Modi will fix everything right, no matter who the BJP CM is).” That was missing in voters’ responses in these states this time.

Modi might not have been able to swing the results in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh despite having two popular chief ministers but the results can’t be seen as a reflection of his popularity.

In Rajasthan, the BJP was facing strong anti-incumbency against Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje whose “queen-like” style of governance seemed to have alienated even those who were “loyal” BJP supporters.

Modi, however, enjoyed goodwill among those disillusioned party loyalists. His rallies drew huge crowds. He might have helped the party to put up a decent show despite the defeat. His popularity rating nationally is still very high, with other contenders and pretenders for the prime ministerial post trailing far behind. He has reasons to worry though.

Popular chief ministers in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh were denied another term by voters as their main concern was not the leaders but day-to-day life issues such as agrarian crisis, unemployment, local-level corruption, and failing delivery mechanism.

These and many more resonate across the country today as the focus moves from assembly to Lok Sabha elections.