A small, unremarkable mosque opposite the Muzaffarnagar railway station in Uttar Pradesh lights up every Friday. But it does not belong to the gods anymore. It belongs to the enemy. The ownership has changed several hands in the past century. It was built in 1918 by the family of Liaqat Ali Khan, Pakistan’s first prime minister. Barely a year after construction was completed, it was endowed as ‘waqf’, implying that ownership was vested in the god.

Then came the India-Pakistan Partition.

Nearly eight decades later, in December 2024, the mosque was declared as ‘enemy property’, under a law that empowers the government to seize such assets, both movable and immovable, left behind by individuals who migrated to Pakistan or China during and after times of conflict.

“The enemy must not hold property in my territory. You never enrich the enemy. You always weaken the enemy when you are at war,” said Arun Jaitley, former finance minister, in the Rajya Sabha during the passage of the Enemy Property (Amendment and Validation) Act 2017.

But like the mosque in Muzaffarnagar, there are 12,611 enemy properties across the country. Many of them have complex legal histories caught in an entangled maze of ownership and family inheritance. And this stubborn issue just refuses to go away. Be it Saif Ali Khan’s properties in Bhopal, the land parcel left behind by the relatives of former Pakistan president and dictator Pervez Musharraf, properties belonging to former Pakistan PM Liaquat Ali Khan in Muzaffarnagar, or the Raja of Mahmudabad whose family has been fighting a legal battle for over 50 years, the ghost of the past continues to appear in courts and Parliament.

The Partition has had a cascading effect on many things. But the enemy properties both in India and Pakistan are a potent mix of Partition’s bloody memories, nostalgia of land and palaces left behind, real estate, and of course politics, making it a vexatious issue.

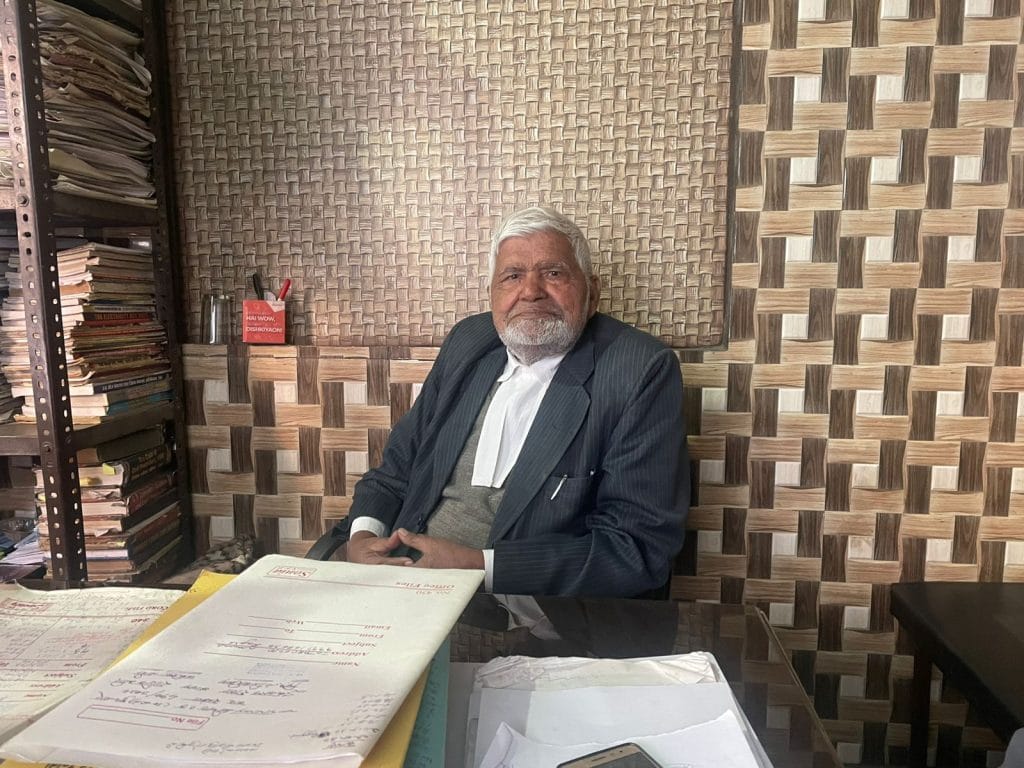

“How can a masjid, which is god’s property, built in 1918 when Pakistan did not even exist, be considered enemy property,” asked MK Rathor, the advocate fighting on behalf of the Waqf Board in the Muzaffarnagar mosque case.

The Narendra Modi government’s 2017 amendment effectively shut the door on any ownership claims of enemy property from legal heirs and consolidated the government’s grip over them. The government argues that it is safeguarding the country’s interests, critics say that the caretakers and heirs of these properties—majority of whom are Muslim—constantly feel the need to defend their allegiance to the nation. To them, this isn’t just a property battle, but a reflection of their struggle for identity in the land of their birth.

In the years since the Enemy Property Act was first passed in 1968, a spate of litigation cropped up across courts in the country. Indian heirs and successors of those who had migrated during the Partition and other wars were staking their ownership rights in these properties.

According to them, they were Indian citizens and certainly not ‘enemies’. So, why should they be punished?

The genesis: a Partition, 3 wars

A house in Muzaffarnagar, a land parcel in Kotana and grand palaces in Bhopal and Mahmudabad became enemy properties almost overnight, long before India or Pakistan came out with legal diktats to assert state control over them. The legal battles around them and the loss of homeland are the long overhangs of the Partition.

What followed has been a seemingly endless streak of tweaking of laws and ever-expanding definitions.

As the realisation of Partition started to sink in on both sides, a meeting of the Joint Defence Council of India and Pakistan was organised on 27 August 1947, a little over a month after the bloodshed as lakhs crossed over an overnight ‘border’. It was chaired by Lord Louis Mountbatten, where Nehru and Jinnah agreed to appoint a custodian of refugees’ property. These custodians would work closely with one another.

With the perils of the Partition persisting, questions of what to do with empty houses, fields, and factories started cropping up. To address these, the governments of the day had come up with measures that aimed to rehabilitate those who had fled, in a fair and organised manner. However, these relatively positive inclinations of restoration and rehabilitation were short-lived. About five months after the Partition, in January 1948, India came up with a new law.

Known as the East Punjab Evacuees (Administration of Property) (Amendment) Ordinance 1948, it barred any “sale, mortgage, pledge, lease, exchange or other transfer of any interest or right in or over any property” by an evacuee or any person who was intending to flee, directly or even through agents or lawyers, on or after the 15 August 1947, unless confirmed by the custodian.

It broadened the definition of “evacuee” to include all who left India since 1 March 1947. It had an equal and opposite reaction. Pakistan adopted an almost identical version of the “evacuee” definition—“any person who by reason of the disturbances” arising out of the setting up of the two dominions, was absenting himself from Pakistan and had property in Pakistan—causing the rights of the actual owners of the property to be diluted.

But there was more.

The next big change vis a vis the treatment toward enemy property came when India was fighting a bloody war with China. The Indian Parliament passed the Defence of India Act 1962, a temporary law that lapsed with the war coming to an end. The 1962 law had termed an “enemy” as a country committing acts of aggression against India, and its citizens. It also went on to expand the definition of enemy properties, including various things from land to gold to shares held in companies of enemy nations.

In 1962, in the wake of Chinese aggression, the Custodian of Enemy Property for India (CEPI) was directed to take charge of Chinese assets in the country, with the aim of vesting them under the Defence of India Act 1962, according to a 2016 Select Committee’s 95-page report. Besides this, the report had added that there were 149 immovable enemy properties of Chinese nationals vested in the Custodian, spread over in States of West Bengal, Assam, Meghalaya, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka and Delhi.

What initially began as a temporary takeover of “enemy” properties under the erstwhile Defence of India Act 1962, paved the way for first an ordinance and then the introduction of the 1968 Act. The war with Pakistan in 1965 only made the case for greater state control over such properties stronger. The 1968 Act allowed the Union government or its designated representatives to seize all such properties of those who had migrated to Pakistan, or even Chinese nationals

Mohammad Nasir, Assistant Professor of Law, Aligarh Muslim University said that although the Tashkent Declaration had a clause saying that the return of properties and assets would be discussed, Pakistan went ahead and disposed of such properties in 1971.

“India continued to hold these properties under the Enemy Property Act of 1968,” Nasir said.

It was a tense session in the Lok Sabha when the Enemy Property Bill of 1968 was introduced. The Bill aimed to continue the vesting of properties left behind by nationals of Pakistan and China in the hands of the Custodian of Enemy Property, replacing the ordinance promulgated on 6 July 1968.

But what seemed like a straightforward piece of legislation quickly turned into a heated debate, with members raising concerns, making demands, and even engaging in linguistic disputes (the Bill was introduced in Hindi, which angered some of the non-Hindi members).

RR Singh Deo, member of the Swatantra Party, expressed deep dissatisfaction with the way the government had handled enemy property.

He pointed out that after the 1965 war, India controlled a significant amount of Pakistani property, but under the Tashkent Agreement, it had returned Pakistani land without ensuring reciprocity.

“Pakistan has about Rs 101 crore worth of Indian assets and goods, which include a ship, 190 inland water vessels, assets of Indian firms and cargo,” said Deo. “As against Rs 27 crore of Pakistani assets held by India.”

Deo went on to add that while he supported efforts of friendship between the two nations, it should not be done at the cost of “honour and property”.

Vikram Chand Mahajan, Member of the Indian National Congress, supported the bill but highlighted a major flaw: the exclusion of Jammu and Kashmir.

“What I submit is that the time has come when we should stop excluding the Jammu and Kashmir State from parliamentary legislation,” said Mahajan. “We are also guilty of creating a feeling of exclusion in that particular part of our country.”

Additionally, Mahajan was troubled by another provision: Indian citizens with legal claims against these properties had no way to recover their dues.

“In the process of preserving their property, you are depriving the citizens of India from executing their legitimate claim against those properties,” he said.

This sentiment changed over the years, most significantly when the 2017 amendment was passed, which completely prevented Indians from laying any claim to ancestral properties.

Of Gods or enemies?

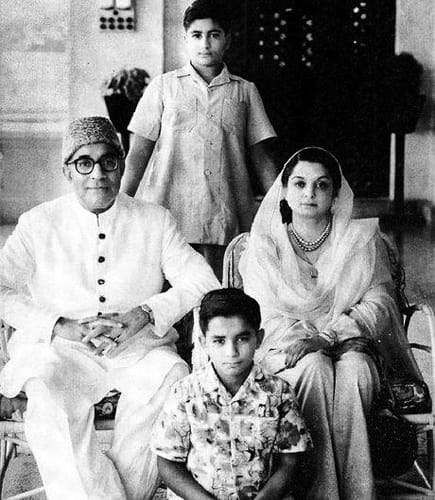

The mosque in Muzaffarnagar was built by Liaquat Ali Khan’s father Rustam Ali Khan, who owned large land parcels in the area. Rustam held many titles, the most prominent being ‘Nawab Bahadur’, which he inherited from his grandfather, Nawab Ahmed Ali Khan.

The Khan family had close ties with the British East India Company, who rewarded them with significant land holdings in exchange for their loyalty, according to historian Muhammad Reza Kazimi’s book about the former PM. In 1919, a year after the mosque was built, Rustam died. His properties were passed down to his son, Liaquat Ali Khan.

“There is no power in the world—whether it is India, Pakistan, England or USA—that can take power away from god. If any property belongs to god—whether it is a masjid, mandir, gurdwara or church—it all belongs to god, no one can change that authority,” MK Rathor told ThePrint.

For the next two decades, Pakistan—whose prime ministership would go to Khan in 1947—was nowhere in the picture. As for the mosque, its current ‘caretaker’ Mujibul Islam said it had been endowed as ‘waqf’ in 1918, right after construction was completed. Since then, the mosque has remained active, and Friday prayers are offered regularly.

“The mosque was even officially recognised as a waqf property in a UP Gazette published in 1944,” Islam told ThePrint. “This was after the passing of the UP Muslim Waqf Act of 1936 which regulated waqf properties in the state.”

But the ghost of enemy property would travel from history. And in 2023, Sanjay Arora, who is part of the Rashtriya Hindu Shakti Sangathan, alleged that it was built on enemy property since the land had belonged to Liaquat Ali Khan’s family. CEPI, after surveying the land in coordination with local authorities, then declared the mosque as enemy property in December 2024.

Now, the lawyer fighting the case on behalf of the waqf is sifting through century-old documents to strengthen his argument. Rathor said there is no question of enemy property in this case. He referred to court judgments, dating back to the 1930s, which mention that Waqf properties are not owned by any man, but by god. On 18 December 1933, the Privy Council, the highest judicial authority in British India, stated that Waqf properties, the “ownership of which vests in God Almighty”, could merely have managers (mutawalli) and no owners.

Rathor also highlighted the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act 1991, passed by the central government when PV Narasimha Rao was prime minister.

“Any religious worship place shall remain in the same position as it was on 15 August 1947. This act is still enforced,” said Rathor. In December 2024, the Supreme Court issued an order preventing civil courts across the country from accepting new cases that challenge the ownership or title of any place of worship.

But it’s not just god whose place is under contention on this piece of land, listed as plot number (khasra) 930 in local revenue documents under Rustam Ali Khan’s name. Four shops that stand on the same plot have also been included as part of the enemy property dispute by CEPI. These include a travel agency and a refrigeration business—these properties generate income for the mosque.

Rathor pointed to a 1976 Supreme Court judgment in the case of Syed Mohd. Salie Labbai vs Mohd. Hanifs, which stated that properties “adjunct to the mosque, which are also used for religious purposes, become as much part of the mosque as the mosque itself.”

According to BJP Minority Morcha member Shadab Shams, the distinction between waqf properties and enemy properties is clear-cut.

“Shatru Sampati or enemy property is not waqf property. If someone has migrated to Pakistan, their property will not be deemed waqf property,” Shams told ThePrint.

Musharraf’s properties

A large amount of agricultural land in UP has been seized by CEPI over the years, but a particular plot received media attention last year. It allegedly has ties to the family of Pakistan’s former president Pervez Musharraf. In 2010, eight hectares of agricultural land were declared ‘enemy property’ in Kotana village, located in UP’s Baghpat district.

“The land allegedly belonged to Musharraf’s relatives, it was not owned by his direct family,” said Pankaj Verma, Additional District Magistrate, Baghpat. “The entire land was auctioned off in 2024.”

The property was in the name of Budhu and Nuru Khan, who left for Pakistan in 1965. However, there is no documentary evidence to prove their connection to Musharraf.

“We have no records to suggest that they were related to Musharraf,” said Verma. “That linkage has been done by the media.”

However, Sub-Divisional Magistrate (SDM) Amar Verma confirmed to PTI that Musharraf’s grandfather and uncle lived in Kotana.

“Former Pakistan president Pervez Musharraf’s father Syed Musharrafuddin and mother Zarin Begum never lived in the village but his uncle Humayun lived here for a long time,” Verma had told PTI.

According to CEPI’s e-auction records, eight properties in Kotana village were put up for sale in August 2024. Starting bids for the plots ranged from Rs 3.08 lakh to Rs 7.98 lakh.

Last year, a two-hectare plot, which allegedly belonged to the Musharraf family, was auctioned off for Rs 1.38 crore, providing a significant cash windfall for the government.

Auction of enemy properties

While a Musharraf or Liaquat Ali Khan property often grabs media attention, India has thousands of land parcels left behind by those who migrated to Pakistan, either immediately after Partition or in later years. A recent e-auction of enemy properties on 13 February included three plots of land in the small village of Seekri (Sikri), some 30 km away from Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh.

Plot 317, surrounded by tall sugarcane fields, is located on the outskirts of the village. It is 1,740 square meters, with a starting bid of Rs 7,51,860. It originally belonged to Ismail, a native of Seekri who migrated to Pakistan after the Partition. Since then, it had been under the administration of the district revenue officer, the tehsildar, who would lease out these properties to locals.

“I was renting this property for Rs 1,200 per bigha per year,” said Abdul Rahim, the former tenant. “It was a three-year lease.”

Rahim and his brother Nasif were sugarcane farmers. They were told to cut down their crops and vacate the plot when a government official from Lucknow visited the property in 2023.

The move was the outcome of an investigation by the Sub-District Magistrate, in coordination with CEPI, which identified properties in Seekri owned by individuals who migrated to Pakistan in the 1950s.

“I was working in that field for 20-25 years,” Abdul Rahim told ThePrint. “Then someone from the government came and told us to clear the field. We were given no notice or documentation.”

Now, the field is barren with overgrown weeds covering the surface.

“There was a sign here [indicating the land was under government control] but the children must have knocked it over when playing their games,” said Rahim.

He added that a lot of villagers migrated to Pakistan after the Partition, leaving behind houses and fields that were in their names.

The last Raja of Mahmudabad

In the history of legal battles involving enemy properties, the case of Raja of Mahmudabad underlines the complexities of citizenship, nationality and a state that is hesitant to let go of control. The case revolved around how his legal heirs—Indian citizens—challenged the law and emerged victorious but only briefly.

The vast Mahmudabad estate—spread across Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand and valued at thousands of crores—was declared ‘enemy property’ after the Raja’s father, the last ruling Nawab, migrated to Pakistan in 1957.

The Raja’s role in the creation of Pakistan was pointed out by Arun Jaitley when discussing an amendment to the Act in 2017. “In 1940, when the Pakistan Resolution was passed by the Muslim League, the Raja of Mehmudabad decided to throw his weight behind the Pakistan Resolution,” said Jaitley.

The minister added that the Raja became a “powerful force” behind Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founding father of Pakistan. After the Partition, the Raja moved to Pakistan in 1957 and became a Pakistani citizen, leaving behind his vast properties.

But separations are rarely straightforward. The Raja’s wife and son, Mohammed Amir Mohammad Khan, stayed back as Indian citizens.

Following the 1968 Enemy Property Act, the Raja’s estate was declared enemy property and taken over by CEPI. These properties included Butler Palace, Mahmudabad Mansion and Lawrie Building in Lucknow’s Hazratganj.

But in 1973, two events would put the enemy property law to the test.

First, the Raja died in London. By this time, his son Mohammed Amir Khan had become a member of the UP assembly and even established his Indian nationality in a civil court, wrote Salman Khurshid, former Minister of External Affairs, in his book The Other Side of the Mountain.

Second, the Raja’s son claimed the properties as his own. According to him, he was an Indian citizen living in the country and not an enemy, as defined under the law.

A legal battle ensued. As some of the properties were located in Mumbai, the case was filed in the Bombay High Court.

In 1995, the Bombay HC declared that CEPI was “merely holding the property for the real owner” and since the Raja had died, the properties should be passed on to his successor.

The government appealed before the Supreme Court, “despite several leaders having requested that the right thing to do was to accept the high court’s verdict,” wrote Khurshid.

On 21 October 2005, the Supreme Court bench of Justice Ashok Bhan and Justice Altamas Kabir also ruled in favour of the Raja’s son, ending a 32-year-long legal battle for the properties.

The state governments of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, where a majority of the Raja’s estate lies, were forced to vacate the properties after having occupied them for decades.

UPA and its ordinance route

The judgment set a precedent, leading to a surge of legal claims by people asserting to be relatives of those who migrated to Pakistan, presenting deeds of gift to claim ownership of enemy properties. The Nawab of Rampur raised concerns over properties linked to family members who settled in Pakistan. India-based relatives of those who migrated to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), also sought ownership of properties left behind.

This would force the UPA government under Manmohan Singh to introduce an ordinance on 2 July 2010, effectively reversing the top court’s judgment and restricting courts from instructing the government to transfer enemy properties from CEPI.

There were disagreements within the UPA cabinet. “I opposed this Ordinance and had to disagree publicly with Chidambaram who was then Union home minister and directly responsible for this piece of legislation,” wrote Khurshid. “The Ordinance had purported to change the law retrospectively making the vesting of property in the custodian irreversible.”

In 2023, Raja’s son Mohammed Amir Khan passed away. His son, Ali Khan Mahmudabad, expressed his disappointment with the government’s decision to pass the ordinances.

“Ever since the ordinance was declared there was shock at the manner in which the executive could try and subvert the law and an order of the Supreme Court, especially through retroactively changing the original law,” Ali Khan Mahmudabad told ThePrint.

Since the UPA ordinance was temporary, a Bill to the same effect was introduced in the Lok Sabha. According to Khurshid, the Bill was sent to a Parliamentary Standing Committee that recommended scrapping it “not because it deprived rightful owners of their rights, but because it allegedly was too accommodative of their claims.”

Bhopal’s blue bloods

The relations between the royals and the political class have influenced how an enemy property can sometimes get friendly treatment, yielding a departure from the succession laws. But in the case of properties belonging to Hamidullah Khan, Saif Ali Khan’s great-grandfather and the last Nawab of Bhopal, these favours have also seen reversals with the change in laws and the government.

The properties include thousands of acres of land both in and outside Bhopal—the Flag Staff House, the Noor-Us-Sabah Palace Hotel, Dar-Us-Salam and Ahmedabad Palace.

“Article 7 of the merger agreement [between the princely state of Bhopal and the government] dealt with the succession aspect and who will stake claim to the throne after the ruler’s death,” said Jagdish Chavani, a senior advocate specialising in enemy property cases.

However, Khan who had three daughters eventually appointed his eldest daughter Abida as his successor. But Abida migrated to Pakistan in 1950. After the death of the Nawab in 1960, the government chose to wait for over a year and announce Abida’s younger sister Sajida as the successor. This was a clear departure from succession laws and kept the property from being declared as an enemy property.

“It was also well-known at the time that Iftikhar—Sajida’s husband and the Nawab of Pataudi—and Nehru had good relations,” said Chavani.

But decades later, in 2015, the Enemy Property Department launched an inquiry into the transfers made to the Pataudi family and declared them enemy properties. The basis of the investigation was a complaint that alleged the property of Bhopal’s Nawab should have been declared enemy property but owing to the Pataudi family’s influence and good relations with the government, they had gotten the same declared as their private property.

The decision was challenged by Saif Ali Khan. “The Madhya Pradesh High Court on 13 December 2024 took note of the 2017 amendment in the law and asked Khan to file his response before the appellate authority for adjudication of disputes concerning enemy property, before 30 days,” said Chavani.

To date, there is no information about such an appeal being filed.

NDA picked up from where UPA had left…

When the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came into power in 2014, a series of ordinances were passed to strengthen the government’s control over enemy properties, seemingly in response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in favour of Mahmudabad. The ordinances ensured that even if the original owner of the property died, no legal heirs—including Indian citizens—could claim ownership. Between January 2016 and February 2017, five ordinances were passed before an amendment to the Enemy Property Act 1968 came into force.

On 14 March 2017, the Enemy Property (Amendment and Validation) Act 2017 was officially passed. The amendment proved critical to the government’s efforts to prevent legal heirs from claiming properties.

“It (the amendment) broadened the definition of “enemy” to include legal heirs of individuals designated as enemies, irrespective of their citizenship, i.e. if the ancestors migrated to enemy countries like China and Pakistan, their heirs were included under the definition of “enemy” even if they were Indian citizens,” Nasir told the Print.

Both the ordinances and amendment were applied retrospectively to all cases since 1968, including properties returned to Mahmudabad.

Arun Jaitley, India’s former finance minister and leader of the Rajya Sabha, specifically referred to Mahmudabad as the ‘one solitary case’ when giving his reasons for the amendment in Parliament.

“He [The Raja] had lost title of these properties in 1965 because of the law which existed during Mrs Gandhi’s Government,” said Jaitley. “So, he ceased to be the owner of these properties in 1965.” Jaitley went on to say that in 1973, since the Raja did not own these properties, nobody could have inherited the properties from him upon his death.

“What the present government has done is to bring about a law which says that once the original citizen of Pakistan’s properties were acquired by the government and were vested in the government of India, after 1965, when it became an enemy state, his successor cannot get that property,” said Jaitley.

Calling the Supreme Court decision to return Mahmudabad’s properties back a “miscarriage of justice”, Jaitley underscored how tenants living in those properties since the 1920s would have to vacate their homes.

“Now this [SC decision] was obviously erroneous because when a citizen of an enemy state loses properties in 1965, how could in 1973 his son inherit the property through him,” said Jaitley.

Jaitley went on to add that if the inheritance of these properties were allowed, it would open the floodgates.

“What will happen is that tomorrow any person who is now a citizen of Pakistan has only to send one family member to India to say, ‘Now I am a citizen of India and acquire properties here and give my properties back,’” said Jaitley, before highlighting that there is no reciprocal obligation in Pakistan for this scenario.

…and passed hurried a legislation

Javed Ali Khan, Samajwadi Party MP from Uttar Pradesh, stressed that the Bill was not just restricted to Mahmudabad but “conveyed a specific kind of message about a particular section of people in this country.”

Members of the Opposition were also quick to express their disapproval of both the Bill and the way it was being passed.

“If the legal heir is an Indian, then this Bill is depriving property to Indian citizens,” said Sukhendu Sekhar Roy, Trinamool Congress MP from West Bengal.

Speaking to ThePrint, Javed Ali Khan recalled how the Bill was introduced on a day when attendance in the Rajya Sabha was particularly low. “They had listed the Bill on Friday evening at 5 pm, which is when private member Bills are usually listed,” said Khan.

As per parliamentary rules, a Bill can be introduced either by a minister or a private member. A member of the house, who is not a minister, is called a private member.

“On that particular Friday evening at 5:30 pm, only 24-25 people were present in the Rajya Sabha, which meant that they almost just met the quorum by a very slim margin,” Khan said.

He went on to say that only seven members of the Opposition were present that day and the Bill was passed in a hurried manner, on Jaitley’s insistence.

The 2017 amendment brought one more fundamental change to the original law.

Earlier, CEPI could only act as a caretaker of enemy properties —mostly land and buildings—by holding them in a trust. However, the amendment gave CEPI the power to rent, lease or sell enemy properties, allowing the government to monetise these assets and generate revenue. It also expanded CEPI’s authority to include cash, bank accounts, jewellery and shares.

In 2023, the government announced plans that it would conduct e-auctions, finally marking a shift in its position from a manager to a liquidator of enemy properties.

CEPI: The custodians

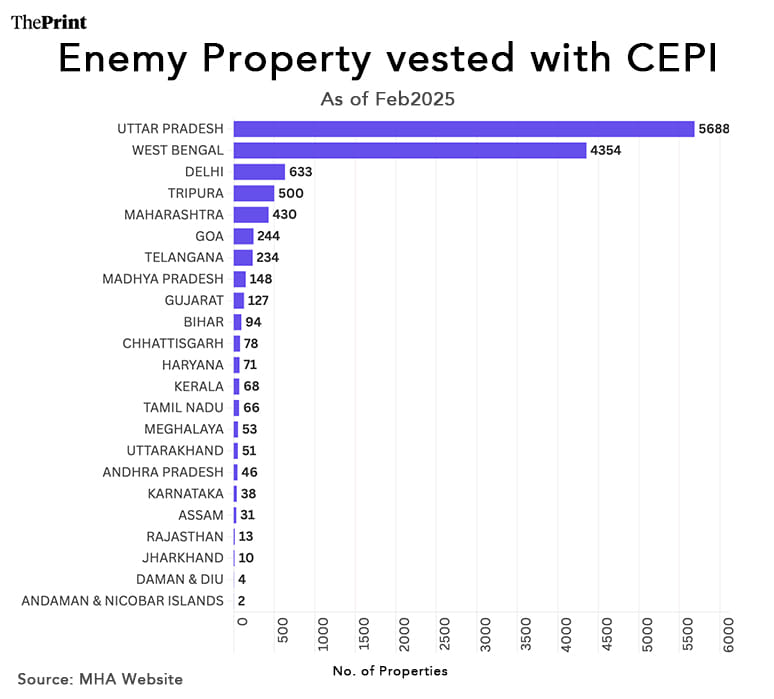

Rs one lakh crore—that is the estimated value of enemy properties being guarded by the Custodian of Enemy Property For India. And 82 per cent of these properties lie in just three states: Uttar Pradesh (5,688), West Bengal (4,354) and Delhi (633). Currently, 12,983 immovable properties across India are vested with CEPI, which provides a tentative state-wise list, as several cases are still under examination.

CEPI can also use these properties as security to raise loans or “carry on the enemy’s business”, i.e. if the property is a hotel, it can continue running under CEPI’s control. Before CEPI sells off properties, a valuation is done by a committee headed by the District Magistrate of the region where the property is located.

The valuation report is then placed before the Enemy Property Disposal Committee, which gives a recommendation to the Central Government on how the property is to be dealt with. CEPI then holds e-auctions to dispose of these properties. Auction details include the property address, area, starting bid, pre-bid Earnest Money Deposit (EMD) and incremental value for each bid.

CEPI also has the power to dispose of movable property, including jewellery.

As of 24 July 2024, enemy properties worth Rs 2,792.10 crore have been sold, according to a response in the Rajya Sabha by Bandi Sanjay Kumar, Minister of State for Home Affairs.

The proceeds from the sale of these properties are deposited into the Consolidated Fund of India, the primary account where the government gathers all of its revenues and borrowings.

Pakistan’s U-turn

Less than two decades after the formation of the nation and three wars later, Pakistan took a stringent view of such properties by selling them off unilaterally. The Tashkent Declaration with India in 1966, which had a clause stating that the return of properties and assets taken over by either side in connection with the conflict should be discussed, was thrown out of the window by the neighbour.

While Pakistan had gone through with selling off these properties, India was still allowing for a case-by-case consideration, in line with established case laws and legal precedents.

After India had come up with the 1968 Act, Pakistan came up with its own equivalent called the Evacuee Trust Properties (Management and Disposal) Act 1975. The law primarily revolved around the management, administration, and distribution of properties left behind by individuals who had migrated to India from Pakistan, following the Partition in 1947.

The evacuees, typically Hindus, Sikhs, and other religious minorities who moved to India during the Partition, left their properties behind in Pakistan. In Pakistan, the government set up a legal and administrative framework to manage these properties, commonly known as evacuee properties.

Speaking to ThePrint, Pakistan-based lawyer Shafiq Ahmad said that the Evacuee Trust Properties (Management and Disposal) Act 1975 was brought in to provide for management and disposal of evacuee properties attached to charitable, religious or educational trusts or institutions like temples, among other things.

However, the Act does not apply to private properties, and vests all evacuee trust properties with the government.

‘The tag of an enemy’

Countless court hearings, hundreds of hours of legal arguments, a favourable judgment by the top court and its reversal later, Ali Khan Mahmudabad, heir to the Mahmudabad estate, hasn’t lost hope. But the enemy tag weighs him down.

“Of course, the tag of enemy for Indian citizens was something that deeply affected him (father) and all of us,” said Ali. “But we also know that these amendments represent the narrow interests of specific people.”

Ali said the 2017 amendment to the law is “fundamentally unconstitutional”, but still has faith in the justice system.

“Our late father, who passed away having fought for his rights as an Indian citizen for his whole life, was always sure that the courts would uphold the constitutional rights of Indian citizens and would give us justice,” Ali said. “My mother, brother and I also believe that we will get justice from the courts.”

In his book, The Other Side of the Mountain, Khurshid underscored how Saif Ali Khan’s father and grandfather, Mansoor Ali Khan and Ifthikar Ali Khan, respectively, played cricket for India. Saif’s mother, film actress Sharmila Tagore (aka Begum Ayesha Sultana) had “enlivened the most distinguished gatherings of Delhi and Bhopal.”

Generations of the Khan and Mahmudabad families have called India their home. Like them, families across India—separated by the Partition and wars—have had to enter legal battles with the government over what they believe is rightfully theirs.

Khurshid understood this sentiment and ended his argument with a rhetorical question.

“What more can one do to be an Indian?”

Allah got his share of land and property in 1947. A new nation was created to accommodate the needs and demands of Muslims/Allah.

Modern India will never allow for Allah’s ownership over Indian land. Anyone favouring such ownership over Indian land is essentially a traitor and must be treated as such.

with such a mindset, one can imagine the great harm the GoI can cause to the waqf properties with their new waqf act when it comes into effect.