For a story based on a dilemma, Rajnigandha had its music crafted to underline the confusion. Salil Chowdhury, fresh off the success of Anand (1970) and Mere Apne (1971), returned to Basu’s team. He was an automatic choice, said Basu to the author. Suresh Jindal too mentions that music sittings at Salil Chowdhury’s Peddar Road flat, named Himgiri, happened during the time he and Basu were scouting for actors. Yogesh, who the author met multiple times, laid out the complete story of how the songs of Rajnigandha were made.

I was a big fan of Basu Chatterji and had seen Sara Aakash thrice. The flash-forward methods he employed in the film appealed to me very much. Incidentally, he too had liked my work and had approached Salil-da with a caveat—I want the same guy who wrote the lyrics for Anand (1970). I had no other work then, and Rajnigandha happened to me. For the title song, Basu-da sketched the outline of the situation of a man arriving to meet the woman with a bouquet of rajnigandha flowers. I was working with Salil-da for a film named Mere Bhaiya (1972) where he had composed a background score using a lot of wind instruments, including the saxophone and the flute. I was fond of the tune and

asked Salil-da if he could reuse it for the title song, which he ultimately did. I wrote to the meter given to me by him. After the recording was done, Lata Mangeshkar told me, ‘Bahut accha likha hai [It has been written beautifully].’ It was a memorable day for me.

Now, there were some discussions between Salil-da and Basu-da. When I asked them, Salil-da said, ‘Basu-da is saying that the song has come out lengthier by a few seconds.’ Perplexed, I enquired how it was possible. And even if it was so, all that needed to be done was to edit the extra seconds. It was then that we were told that the song sequence had already been shot! The song was in the background and hence there was no lip-sync. I had written the second antara as ‘Apna unka kya doon parichay Pichle janmon ke naate hain

Har baar badalkar ye kaya Hum dono milte aate hain, Dharti ke is aangan me,

Rajnigandha phool tumhare . . .’

Then I saw part of the film and the song sequence at the studio, and my general feeling was that the lyrics did not tie in well with the situation. I went to the Irani restaurant across the street, sat down at a table, and did a rewrite of the second antara. It had a more contemporary feel. To Basu-da, it would have made no difference, but I would have rued the fact that my song failed in its attempt to capture the essence of the film. ‘Rajanigandha Phool Tumhare’ brought Salil back to the Binaca list after Anand. The song, with the leading notes of Sunil Kaushik’s twelve-string guitar, is partly reminiscent of the prelude of Simon & Garfunkel’s Sound(s) of Silence (1964), and remains a favourite with many even forty-five years later, and not just on account of nostalgia.

If Lata’s impeccable rendition of this intricate melody is most loved, ‘Kai Baar Yun Bhi Dekha Hai’ surely is the cherry on the cake. Discerning, sharp, with a reverb creating a halo of sorts. To top it all, the dazzling songs were situational, certainly not decorative adjuncts in a story where silence was used to communicate more than the words spoken.

In a discussion with the author, Preeta Mathur dissects the song situation for ‘Kai Baar . . .’ as heard from Dinesh Thakur: You see, the unusual part of the song was that it was not ready when the picturization was to take place. It was not yet fixed or decided. Basu-da gave them the background. Both the actors were told, ‘These are the emotions. You have to portray them.’ Just that, nothing else.

But if you see the song on screen, it so beautifully matches the visuals and the expressions of the characters. This is the brilliance of a director and an editor. How they mix the song with the visuals to fit in with the emotions. That was amazing. Basu-da had given them these instructions. There is this dichotomy in her mind. Should she go with him? Should she not? She is confused. And he isn’t saying anything. Probably he is afraid of rejection, or he does not want to preempt. And she is thinking, ‘Why doesn’t he say something? Why doesn’t he help me decide?’ The taxi ride, you see—he is very careful, very concerned, very courteous but not saying anything more. He is just not taking it to the next level despite doing all that is needed in a manner most decorous . . .This marked a rare occasion in Mukesh’s career when he was not singing for the male protagonist. Rather, his song represented the crux of the story, and he pulled it through with his deep bass and controlled passion. This thought-provoking song on 2×4 with syncopated beats, a touch of Bossa Nova and arranged with lots of brass and wind obligatos, came to Mukesh on the rebound; engaging Lata as envisaged originally would have cost the producer Rs 3000.

Mukesh charged only Rs 1000, a token amount, mentioned Basu to the author. The change of playback singer was the reason for the delay in the recording. Said Yogesh about his writing for the already composed song by Salil Chowdhury: Salil-da, who was a great poet himself, would never permit me to be inspired by him as far as writing lyrics was concerned.

He would shoo me away if I followed his style of writing. ‘Kai Baar Yun Bhi Dekha Hai’ was written to the tune of a Bengali song Salil-da already composed. But I had to use my

imagination to fit the situation. Salil Chowdhury was another reason why the song was married so nicely to the visuals. His expertise in handling background scores came into use; one would notice the rhythm picking up only when the taxi starts moving. The background music was used to signify the moods of the characters too, and one might go back and check Chowdhury augmenting Deepa’s tension by adding a C sharp note in the progression ‘F-G-F-C(low) / F-G-F-C(high)’, in the scene when she has been kept waiting by Sanjay for over an hour. The composition also helped separate the characters of the two cities.

Delhi saw a dominant use of Indian instruments, both string and wind, while Bombay’s was more rhythm-based. George Fernandez’s muted trumpet was one of the attractions in ‘Zindagi Kaisi Hai Paheli’ (Anand, 1970). The instrument found prominent use in Rajnigandha too, especially in the sequences involving Bombay. And in ‘Kai Baar.’ . . . And the Aftermath. Over two months and Rs 7 lakh later, Rajnigandha was complete. Being a rookie producer working with almost all debutants, Famous Cine Laboratories and Studios had given Jindal a 50 per cent credit on the processing costs. While this would have

acted as a buffer, the market reaction to the sales pitch was dismal.

Distributors rejected the film simply after hearing its name. ‘Kiski gandha? Kaun si gandha?’ They would ask, and surmise—‘Class ki boo aati hai (reeks of class).’

Jindal went to quite a few of them, including the financiers of Anubhav (1971), a Sindhi family. ‘Tukka lag gaya, lag gaya (we just got lucky),’ they said about the success of the film, not interested in taking any more chances. Among other distributors who backed out was Shakti Raj (a distribution company floated by Shakti Samanta and Rajesh Khanna). They had held on to the agreement for three months, and then dropped it, Jindal said to the author.

It was the Rajshris once again. They picked up the film almost two years after it was canned. It is not known what the selling rate per territory was, but assuming a mark-up of 25 per cent to cover interests and producer’s profit, Rs 1.50 lakh per territory—a total of six territories—should have been a decent bargain. Jindal sold it for £16,000 in the UK, which, in 1974, translated to approximately Rs 3 lakh.

The censor certificate carried the spelling Rajanigandha, the way a Bengali would pronounce it. The title read Rajnigandha. The spelling on the censor certificate was courtesy of the clerk. To change the same would have taken another three months. Jindal decided to let it go to avoid any further delay in the film’s release. Rajnigandha was released on 20 September 1974, 10 days after it received the film certificate.

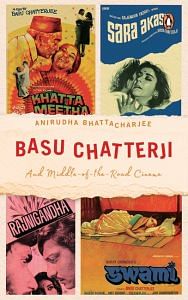

This excerpt from Anirudha Bhattacharjee’s ‘Basu Chatterji’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House.

This excerpt from Anirudha Bhattacharjee’s ‘Basu Chatterji’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House.