The family background of Dr Ambedkar also played an important role in shaping his thoughts and ideas. Dr Ambedkar belonged to the Mahar caste in Maharashtra; many of the members of this caste were a part of the British Army. This position gave them social mobility and enabled their migration to cities. Military service also exposed them to British institutions and to the imagination of a new political order and opportunities. This social advancement in urban settings also encouraged them to get educated. The Mahars were also influenced by the bhakti movements in Maharashtra, which believed in the rejection of caste distinctions. Thus, both social mobility and education engendered an egalitarian conscience within the community. Jaffrelot notes that Dr Ambedkar inherited all these legacies and invented his own vision.

Dr Ambedkar’s father was a part of the British Army. As education was mandatory for the children of military personnel, everyone in the Ambedkar family, including the women, was literate. Dr Ambedkar went to a cantonment primary school and later completed his graduation in Bombay.

The support of two individuals proved to be influential for Dr Ambedkar. The first was the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III. After graduation, Dr Ambedkar initially joined as a lieutenant in the army of the state of Baroda in 1913, but later decided to pursue higher studies in the US with financial support from Maharaja Gaekwad. The young man received a scholarship on the strength of his intelligence and hard work, and on condition that after completing his studies, he would return and serve the state of Baroda for ten years. The other individual was the Maharaja of Kolhapur, Chhatrapati Shahuji, who, impressed with Dr Ambedkar’s capability and potential, supported his further studies in London and his efforts towards launching the newspaper, Mooknayak. Without the financial support given by these two maharajas, Dr Ambedkar would not have been able to pursue his higher education abroad. Foreign education exposed him to a wealth of ideas, a number of scholars and a sense of pragmatism. Jaffrelot notes:

[T]he decisive factor in shaping his revolt against the caste system was his education overseas, which exposed him to egalitarian values and allowed him to interrogate the mechanisms of caste. On returning to India, he further refined his tools of sociological analysis to better contest the social system of which untouchables were the prime victims.

This influence on Dr Ambedkar has also been documented by other leading scholars such as Eleanor Zelliot. She wrote:

The three years Ambedkar spent at Columbia, 1913-1916, awakened, in his own words, his potential. Columbia was in its golden age, and a list of Ambedkar’s professors reads like a catalogue of early twentieth-century American educators. The transcript of Ambedkar’s work at Columbia reveals that he audited many classes, more than he could have taken for grades, including such subjects as ‘railroad economics’.

Furthermore, historian Anupama Rao notes: ‘Ambedkar was in the [New York] city at a fertile time: the modern social science disciplines were just beginning to take on clear definition . . . Attention to associational dynamics on the [Columbia] University campus reveals key connections between public activism, a diversifying student body and the politics of

the classroom’. Some professors at Columbia had a great influence on his thoughts on democracy and society. As scholar Scott Stroud notes: ‘Later in life, Ambedkar would see philosophical tools such as John Dewey’s notion of democratic community as an ideal or hope that loneliness could be erased and bridges with dignity be built between agreeing and disagreeing community members.’

In an article written for the Columbia alumni magazine in 1930, Dr Ambedkar made a nostalgic note of his time in the US, ‘The best friends I have had in my life were some of my classmates at Columbia and my great professors, John Dewey, James Shotwell, Edwin Seligman and James Harvey Robinson.’ Dr Ambedkar also examined the problems of African Americans in the US. Later on, he would use these experiences and learnings as a comparative perspective during the drafting of India’s Constitution. Zelliot noted, ‘It is more likely that in those early years in America his own natural proclivities and interests found a healthy soil for growth, and the experience served chiefly to strengthen him in his life-long battle for dignity and equality for his people.’ Dr Ambedkar maintained his intellectual ties with Columbia University, even after graduation. The University also kept in touch with him; in 1930, the Alumni Bulletin reported his address at the Round Table Conference in London.

Dr Ambedkar’s time at the London School of Economics (LSE) was documented in the archive files released during an online exhibition held by LSE in June 2021. The online exhibition made ‘available for the first time the entirety of Ambedkar’s LSE student file’. Dr Ambedkar first became a part of LSE in 1916 when he was twenty-five years old. He is believed to be the first Indian to receive a doctorate from the LSE. In 1920, Prof. Seligman of Columbia University wrote to Prof. Herbert Foxwell of LSE, recommending Dr Ambedkar and requesting Foxwell to help him in his research. Since Dr Ambedkar already had a doctorate, Prof. Foxwell wrote to the school secretary, Ms Mair, that ‘there are no more worlds here for him to conquer’. But Dr Ambedkar wanted to study further. He acquired his second master’s and a PhD from LSE. His professors at LSE included influential intellectuals like Leonard Hobhouse and Halford Mackinder, among others.

In London, Dr Ambedkar also pursued law from Gray’s Inn to become a barrister-at-law. He studied law, as it provided him with the tools that would help him assert the rights of marginalized social groups. Dr Ambedkar wanted to equip himself with the knowledge of legal systems, as he often referred to principles of law to question acts of injustice in India. He recognized that legal practice was also a means for resistance and contestation. He once mentioned that the law gave him ‘liberty and free time to perform social work’. He also recounted later that ‘legal practice and public service are thus the alternating currents in my life’.

LSE records also indicate that while he was in London to attend the Round Table Conferences, Dr Ambedkar met some of his former classmates and professors at LSE. In 1932, his former supervisor Edwin Cannan wrote a letter to William Beveridge (then director of the LSE) to ask him to engage with Dr Ambedkar during his stay, and described him as: ‘I always said he was by far the ablest Indian we ever had in my time.’ Dr Ambedkar also ‘maintained a relationship with LSE, and there is evidence that he was heavily involved in financing students from Dalit communities to be able to study abroad, including at LSE, in the 1950s’.

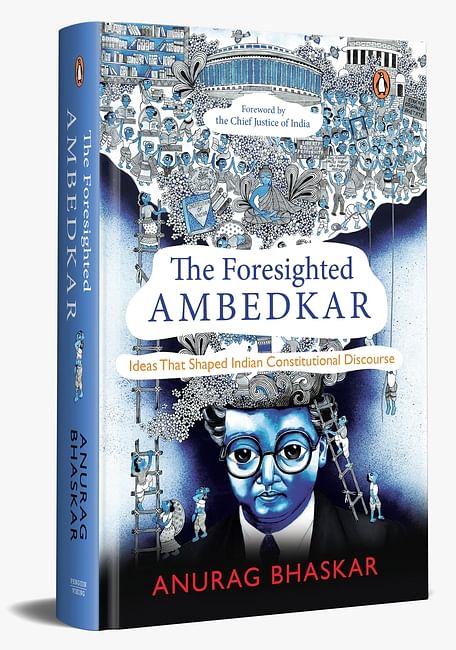

This excerpt from The Foresighted Ambedkar: Ideas That Shaped Indian Constitutional Discourse by Anurag Bhaskar has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from The Foresighted Ambedkar: Ideas That Shaped Indian Constitutional Discourse by Anurag Bhaskar has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.