There are two competing visions of the modern nation-state soldier: (1) that of a professional, distanced from civilian life, formed through meticulous training and discipline and (2) that of an armed peasant or worker. British imaginings of the Indian soldier in the service of the British Indian Army operated between these two poles. The sipahi was an “occidental soldier,” subject to military bureaucracy, laws, and discipline, and yet at the same time he was still “recognizably Indian,” a “pseudo-historical” subject, an accident of the ever-changing definitions of the mythical martial race. In the first vision, he is no longer a civilian or a primitive, which is a dramatic shift from his earlier being, whereas in the second vision he is essentially unchanged, just armed and better trained in violence. The Pakistani military’s dependence on what the British Raj regarded as martial areas for troops lasted until as late as 2001, where it continued to rely on an expanded pool of districts within Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) as its primary recruiting ground. Many officers and soldiers I interviewed suggested that men from the martial regions of Punjab and KP had a greater willingness and ability to serve because of their extended exposure to the military lifestyle. This made it easier for boys coming from families and districts in which the ethos of the army was not so alien to adapt to the demands of military discipline. Despite this, as the earlier passage shows, what happens in the military training institution is looked upon as a complete metamorphosis of the being subjected to it. The imaginings of the British Indian Army continue to haunt the modern Pakistani jawan (young man). A dual articulation of his subjectivity positions him as socialized into martialness and already half a fauji (military man) yet also the uncouth primitive who has to be trained into an occidental soldier.

The figure of the jawan, the subaltern soldier of the Pakistan Army, is interrogated within this chapter from two perspectives. First, I look at how the military institution sees its soldier class; what aspirations, desires, and apprehensions it carries; and what kind of soldier it wishes to create. Second, I investigate how the soldier lives and experiences this molding, the experiences he brings to these rituals of transformation, and the ways he copes within these regimes of discipline. The descriptions that emerge from juxtaposing these perspectives bring into sharp relief the split visions around the soldier-subject: the instinctual given of the martial race versus the necessity of the monotonous, steady inculcation that is soldier training; the image of the honed diamond that emerges after training versus that of the mindless automaton he is reduced to; and the soldier figure who follows orders in battle much like a machine versus the soldier who is paralyzed in battle and has to be cajoled like a child or taunted and humiliated to fight.

The fluidity of these depictions was apparent in the inability of my interlocutors to present a settled image of the soldier—the picture they presented was incoherent and unstable. A sense of incompleteness haunted my conversations with soldiers. For as I sat with these men, talking with them about their lives, hopes, and anxieties, I was conscious that while they said much, there was much that remained unspoken. This inhibition sprung not so much from the confines of our gender or class differences or an awareness of the watchful gaze of the military—although I am sure that too must have played a part— but instead from self-censorship; from carefully cultivated habits of the heart, mind, and body; and a resignation to the inability of knowing and the impossibility of accessing the self. These were halted, silent conversations, even when words flowed freely.

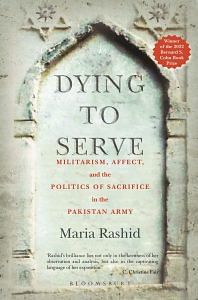

This excerpt from Maria Rashid’s ‘Dying to Serve: Militarism, Affect, and the Politics of Sacrifice in the Pakistan Army’ has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

This excerpt from Maria Rashid’s ‘Dying to Serve: Militarism, Affect, and the Politics of Sacrifice in the Pakistan Army’ has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.