My father was very proud of his hardworking son who would bring his lunch to the factory even as a schoolboy. However, that too was short-lived. It vanished when the woman within me wrestled her way to claim my body and my being. Although she had always been inside me and gave glimpses of her strong hold over my body and behaviour, it was only when I was in, say, Class 7, that the feminine within began to be more and more evident.

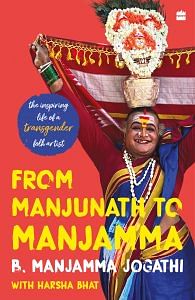

While some say it is a sort of abnormality, in our part of the country, especially in the northern districts of Karnataka, it is seen as our lives being taken over by the Goddess we worship. It is her tale, the tale of Yellamma, that we as Jogathis dedicate our lives to telling by singing, dancing and seeking alms. It is through her grace that the feminine power chooses to manifest through us and that is how we in northern Karnataka see ourselves too—as an embodiment of the divine.

The turmoil within, though, is beyond description and I wish it upon none else. The pain is something that can’t be shared with anyone else. They are not the feelings of coming of age, of a boy turning into a man or a girl into a woman. The emotions are neither of a boy, nor a girl, and can’t be shared with either. I didn’t really feel welcome among the boys or the girls.

I couldn’t make friends with boys since I would feel shy to talk to them, nor did I feel like I belonged among them or was one of them. Whenever I would try to talk to them, they would shoo me away saying I didn’t belong as I was ‘acting like a girl’ and it made them uncomfortable and embarrassed. ‘We are boys and you aren’t like one of us. So you should stay away from us, it is embarrassing. People will start talking ill about us and probably create stories about our association with you. Please stay away,’ they would say.

I yearned to talk to my female classmates but didn’t dare to. On the few occasions I did, they would keep their distance. Not like I could blame them. I was, after all, a boy, I dressed like one. They would smirk at my gait that was beginning to appear feminine. They would talk among themselves, wondering why I acted like a girl at times and wanted to be with them. My talk, my walk, my expressions, my emotions and the way they manifested physically in terms of my body language were all feminine.

Despite the awkwardness, I still wished to hear them talk, to be like them and share my feelings with them. I wanted to tell them I was like them, I felt like them. But how was I to do this? They wouldn’t accept me. They saw me as a boy, but I knew I didn’t feel like one. I was a woman in my understanding of myself—the feminine gentleness within, the motherly nature of caring and taking responsibility for household tasks reserved for women back then, my feminine way of viewing the world, while on the physical plane too the way I walked, sat, moved and behaved was very womanly.

It wasn’t girly, it was womanly. What I mean is that I began to imitate my mother, wear a towel across my chest the way she would drape her saree pallu, draw a rangoli in front of the house after waking up, help with the cooking and wash vessels after we were done eating, do pooja even at the cost of getting yelled at by my mother day in and day out. It was an inexplicable situation both within myself and for those around me.

I must have been around twelve or thirteen years old at the time. It started when I was, say, in Class 7 but the feelings intensified when I was in Class 9. At the same time, people around me began to sense a feminine side emerge more prominently in my way of being.

My tryst with the stage and of playing a character beyond the dualities of gender too began then. When I was in Class 7, we staged a drama called Thiruneelakantha in school. At that time women didn’t take part in dramas; men would shave off their facial hair and play female roles. Our teacher, Basappa Master, offered me the role of Paramatma, God himself. But since he was organizing the play and was one of the first to be sensitive to my changing self and feminine emotions, he also had in mind another role for me.

‘Will you dance as a girl?’ he asked. I wasted no time agreeing. It was clearly what I wished to do, what I longed to experience—to dress like a girl, to dance like one, to be seen as one.

After I was done playing my Paramatma role in the play, I changed into a skirt and full-sleeved blouse and danced like there was no one watching. The feel of the skirt around my waist inspired me to dance with a zeal and joy I hadn’t known before. Basappa Master announced my name as Bengaluru Lata and I danced, swaying and moving like a girl. I was overjoyed with the way the audience responded.

And that was, in many ways, the beginning of my dance of destiny.

This excerpt from B. Manjamma Jogathi and Harsha Bhat’s ‘From Manjunath To Manjamma’ has been published with permission from Harper Collins India.

This excerpt from B. Manjamma Jogathi and Harsha Bhat’s ‘From Manjunath To Manjamma’ has been published with permission from Harper Collins India.