The antiquity of Kumbh is still unclear, as there is no authentic written history. It is said, Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador to the court of King Chandragupta

Maurya of Patliputra, visited the Kumbh Mela in the fourth century BC. Today, Patliputra is known as Patna, the capital of the eastern state of Bihar.

We get the first written evidence of the Kumbh Mela in the travelogue of Xuanzangor Hsuan Tsang, a ChineseBuddhist monk, scholar, traveller, and translator, who travelled to India circa 630, during the reign of the famous Hindu king Harshvardhan.

In his eyewitness account, he wrote that half a million people had gathered on the banks of the Ganges at Prayagraj (Allahabad) during the Hindu month of Magha for Kumbh Mela. The King along with his ministers, scholars, philosophers, and sages, participated in the Mela celebrations, where he distributed gems and jewels, gold, silver, and even his clothes, in charity.

In the eighth century, when Hinduism was losing its relevance due to the advent and domination of Buddhism, Jainism and other faiths, a saint and religious reformer from southern India, Shankaracharya, popularised Kumbh as a religious gathering among the common masses.

He successfully established the Kumbh Mela as a meeting place for people with religious and spiritual inclinations. As a natural consequence, with each passing year, more and more people started to attend the fair.

Also read: You don’t have to be a Hindu to be moved by Kumbh Mela. It is about the simplicity of faith

Later, Mark twain, the father of American poetry, wrote after visiting the Kumbh Mela in 1895:

‘It is wonderful, the power of a faith like that, that can make multitudes upon multitudes of the old and weak and the young and frail enter without hesitation or complaint upon such incredible journeys and endure the resultant miseries without repining. It is done in love, or it is done in fear; I do not know which it is. No matter what the impulse is, the act born of it is beyond imagination, marvelous to our kind of people, the cold whites.’

We found a lot of literature about Kumbh in Sanskrit, Hindi, and other Indian languages. According to Sir Jadunath Sarkar, a noted historian and Bengali aristocrat:

‘The first English account of the Kumbh that we have was written in 1796 when Haridwar was in the possession of the Marathas. On 8th April 1796, an English officer named Captain Thomas Hardwicke, accompanied by Dr Hunter paid a visit to Haridwar during the mela held on that date which was the Mesh Sankranti.’

In so many ways, the Kumbh Mela facilitates the coexistence of diverse traditions which have partially sacrificed their theological, ideological, cultural, and social differences, in order to engage with one another and to seek understanding and even harmony.

Religious teachers from heterogeneous traditions, converge in this multi-cultural, multi-faith event with their own perspectives, purposes, and prejudices. While they share the same space with each other, many of them also share sentiments of mutual acceptance and assimilation and thereby impart the spirit of pluralism through their discourses at the Kumbh Mela.

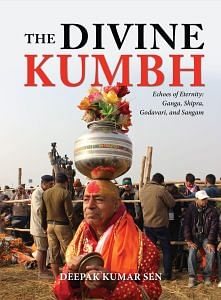

This excerpt from ‘The Divine Kumbh’ by Deepak Kumar Sen has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

This excerpt from ‘The Divine Kumbh’ by Deepak Kumar Sen has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.