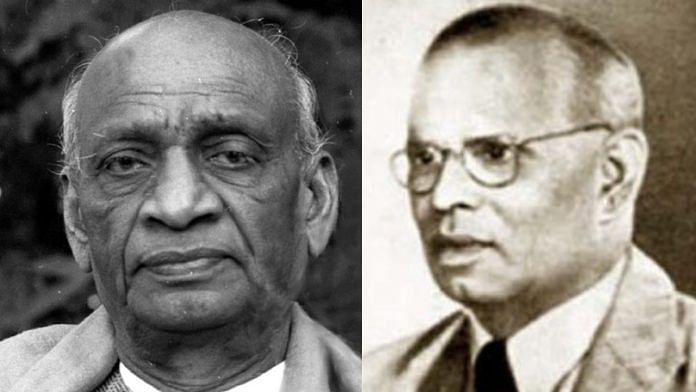

The first thirty months of India’s tryst with integration of the princely states within the new administrative and political architecture of the country is a marvel by itself. Many Churchillians thought that Independence was the beginning of the end, for they believed that India was only a geographical aggregation rather than a civilizational entity. The near-smooth transition from a dominion to a republic is actually a grateful nation’s tribute to Sardar Patel and V.P. Menon.

While Hindol Sengupta does talk of Patel as The Man Who Saved India, the role of his able and trustworthy lieutenant V.P. Menon cannot be underestimated. While the Sardar laid down the broad policy, the responsibility of drafting the Instruments of Accession, and ensuring that all the princely states signed on the dotted line – both for the Instrument of Accession, as well as the Agreement on Merger – fell on Menon, who also ensured that India chose to call itself the ‘Dominion of India’ instead of the ‘Dominion of Hindustan’, as preferred by an important section of the British establishment.

The Dominion of India thus became the natural ‘successor state’ to British India – else Pakistan could have staked a claim in the territories held by Portugal and France, especially in pockets that had substantial Muslim populations. Menon thus showed a rare insight by insisting on India, rather than Hindustan, as the chosen name for his nation. Even our Constitution says, ‘India that is Bharat’, thereby reinforcing the primacy of India as the name of our country.

Also read: The woman who cooked her way into the story of India’s freedom movement

It is true that the Chamber of Princes, and some of the larger princely states, did want to assert their ‘independence’, and collectively they could have posed a challenge, for they occupied roughly two-thirds of the country’s area and 48 per cent of its population. However, they were hopelessly disunited, lived in a world which was frozen in time, and most importantly, were no match to the movements for popular democracy in their states. Moreover, the imperial power which had propped them for over a century was no longer willing to offer anything beyond platitudes.

From the time of Subhas Bose’s presidency, the Congress had taken the view that the states were an integral part of India, and that the Praja Mandal or the All-India State Peoples’ Movement had to be supported, though they were reluctant to openly declare their support against the Indian princes. This was more ‘tactical’ as it was clear that once the British paramountcy lapsed, the princely states would collapse like a house of cards. The Government of India Act of 1935 did not make any express commitment to the princely states, and while the British did encourage the states to contribute liberally to the war effort, they were not making any commitments on behalf of the Crown.

One must not forget that over fifty of these states had well-trained standing armies and that many troops had seen action in the World Wars. Although, in retrospect, it appears that their internal prejudices and differences were superficial, the fact of the matter is that ‘this is what defined their lives’ (table of precedence, gun salutes and personal entitlements), and they were willing to commit the resources of their state to achieve these distinctions.

Also read: For Tulu community in India, ‘Bhuta’ masks are charged with magic, meaning and myth

Some individual officers of the Indian Civil Service (ICS), especially those on secondment to the political service, working as residents in the princely states and in the political department, had developed a very good rapport with the individual states. But that was never looked at approvingly by the viceroy’s office or the secretary of state, and as also by Patel and Menon.

The inclusion of the representatives of princely states in the Constituent Assembly was a masterstroke: the princely states could not complain that they had not been consulted in the new governance architecture, and all their assertions and claims were responded to with flourish and finesse. Although, as a matter of principle, the representatives of the states had to be ‘elected’, in many instances they were nominees of the princes, and some like C.S. Guha represented more than one state, like both Manipur and Tripura, in this instance. Be that as it may, the map of 1950 was quite different from that of 1947, and though there were variations between the states under governors and states under raj pramukhs, the map becomes more recognizable when seen with the present states and UTs.

This excerpt from Sanjeev Chopra’s We, the people of the States of Bharat has been published with permission from Harper Collins