Just as we’re rising from our chairs to leave, her grandson Partha Sarathi Mahato, who is—like Baidyanath was—a teacher, asks us to remain seated. ‘Partha da’ has just a few words to say to us.

And the penny drops.

Who were those people she kept cooking for other than her large family? Who were the sometimes five–ten–twenty people whom Baidyanath kept getting her to prepare

meals for?

‘Those meals she cooked were for the revolutionaries,’ says Partha da. ‘Those in the underground resistance, often on the run or hiding in the forest.’

We sat there in silence some moments. Completely overwhelmed by the sheer sacrifice of this woman who never had a moment to herself, for herself, in almost her entire life

from age 9.

Also read: Khadi, cash, chauffeurs: How a Malayali queen impressed Gandhi

If what she did in the 1930s and 1940s wasn’t participation in the freedom struggle, what was?

Her son and others look at us, surprised that we had not understood this. They had taken it for granted that we knew.

Did Bhabani know what she was doing and for whom?

Well, actually, yes. She just did not know their names or recognize them as individuals. Baidyanath and his fellow rebels organized the transfer of food cooked by the village women to those on the run, in a way aimed at protecting both as best they could.

Partha da, who has researched the situation in Puruliya of that time, would explain to us later: ‘Only a few better-off families in the village were to prepare meals for however many

activists in hiding there were on a given day. And the women doing this were asked to leave the cooked food in their kitchen.

‘They did not know who it was who came and picked up the food. nor did they know who the individuals were that they were cooking for. The resistance never used people from the village to do the transportation. The British had spies and informants in the village. So did the feudal zamindars who were their collaborators. These informants would recognize locals carrying loads to the forest. That would endanger both the women and the underground. nor could they have anyone identifying the people they sent in—probably by nightfall—to collect the food. The women never saw who it was lifting the meals.

‘That way, both were shielded from exposure. But the women knew what was going on. Most village women would gather each morning at the ponds and streams, tanks—and those involved exchanged notes and experiences. They knew why and what they were doing it for—but never specifically for whom.’

The ‘women’ included young girls barely in their teens. All of them risking very serious consequences. What if the police landed up at Bhabani’s house? What would become of her and the family that depended on her, as she points out, for ‘everything’?

Largely, though, the underground protocols worked.

Yet, families embracing swadeshi, the charkha and other symbols of resistance to the British were always under surveillance. The dangers were real.

So what did Bhabani cook for those in hiding? She has Partha da explain it to us after our meeting. Jonar (maize), kodo (ditch millet or Indian cow grass), madwa (ragi or finger millet) and any vegetables the women could get. Which means, thanks to Bhabani and her friends, they could often consume the same staples they had at home.

On some occasions, they had puffed or flattened rice—chinre (poha) in Bengali. The women sometimes also sent them fruit. Besides which they would eat wild fruit and berries. One item the old-timers recall is kyand (or tiril). In more than one tribal language, that simply means ‘fruit of the forest’.

Partha da says his grandad, as a young husband, would suddenly show up and place orders with Bhabani. When this was for friends in the forest, it inevitably meant preparing food

for many more people.

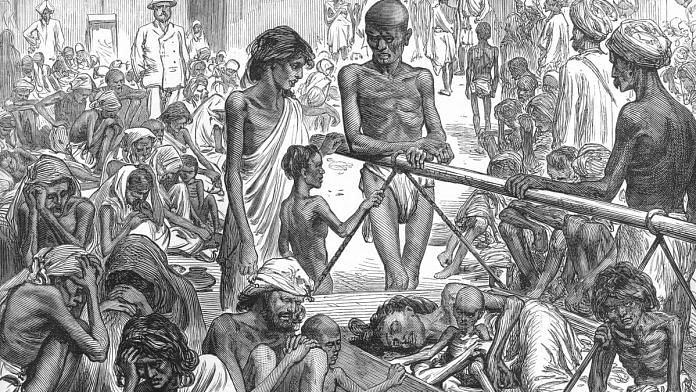

And it wasn’t just the British who were a problem. In the 1940s, her load was heaviest during the years of the Great Bengal Famine. The hardships she must have endured in that

period defy the imagination.

Also read: How Punjabi journalists became ‘willing tool’ for extremists and police after Blue Star

So, looking back, what does she think of Gandhi, ahimsa, and satyagraha now? While she is outspoken and to the point on most things, she finds questions she sees as larger philosophical ones confusing. What is clear is that she was and remains idealistic on her own plane. That she knew what she was doing—risking her life—in aiding the resistance to the Raj.

Her adventures continued after Independence. These too, were marked by idealism and caring for others. In the 1950s, a huge fire razed the entire mohallah or neighbourhood where the family still lives. It destroyed all stocks of grain held by people there. Bhabani brought in grain and produce from her own family’s lands in the village of Janra. And sustained the entire community for weeks till the next harvest.

In 1964, a major communal flare-up rocked nearby Jamshedpur in what was then Bihar. Its flames scorched some villages in Puruliya as well. Bhabani sheltered many Muslims of her village in her own house.

Two decades later, an already ageing Bhabani killed a wild cat that was raiding the livestock of the locals. She did that, says Partha da, with a stout piece of wood. It turned out to be

a khatas, or small Indian civet, coming out of the forest.

We look at Bhabani Mahato with renewed respect. I remembered the story I had done on freedom fighter Ganpati Yadav. A courier of the underground in Satara, he carried food into the forests for the fighters hiding out there. He was still cycling 90 kilometres a day at 98 when I met him. I loved doing that story on the wonderful man.

But had failed to ask him: he carried so much food into the forests at great risk, but what about his wife who did the cooking?

She was away with relatives when I visited him.

Ganpati has passed, but our encounter with Bhabani makes me realize one thing: I need to go back and speak to Vatsala Ganpati Yadav. And have her tell her own story.

Bhabani also makes me recall those powerful words of Laxmi Panda, the Odia freedom fighter who had joined Netaji Bose’s Indian National Army and had been in their camps, both in the forests of Burma (now Myanmar) and in Singapore.

‘Because I never went to jail, because I trained with a rifle but never fired a bullet at anyone, does that mean I am not a freedom fighter? I only worked in INA forest camps that were targets of British bombing. Does that mean I made no contribution to the freedom struggle? At 13, I was cooking in the camp kitchens for all those who were going out and fighting, was I not part of that?’

Bhabani, like Laxmi Panda, Salihan, Hausabai Patil and Vatsala Yadav, never received the honours and recognition she truly deserved. In the struggle for India’s freedom, all of them

fought and acquitted themselves as honourably as anyone else.

This excerpt from P. Sainath’s The Last Heroes has been published with permission from Penguin India.

This excerpt from P. Sainath’s The Last Heroes has been published with permission from Penguin India.