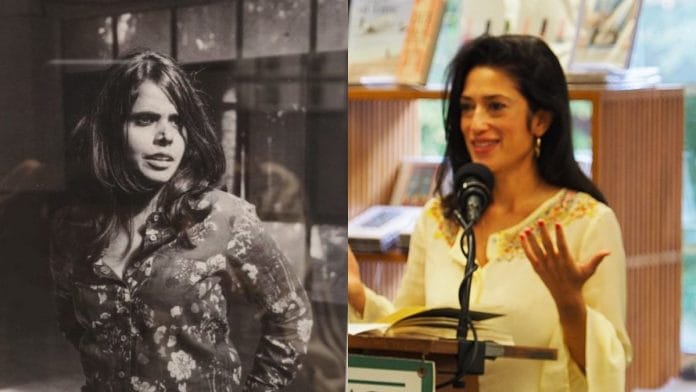

How I Write’ features interviews with writers, where they delve into their craft, life, and more. Below is an excerpt from a candid conversation between authors Meena Kandasamy and Fatima Bhutto.

FB: There are a lot of good things about the glory of publishing, such as being invited to give talks, but do you have any warnings for first-time authors?

MK: The first thing that I would like to say is that criticism of your writing is not a criticism of you. Sometimes at poetry workshops I tell young people, ‘This poem is perfect. Just take the last two lines out.’ Or, ‘Everything is good. Just move this to the beginning’, and they act like their writing is precious. Your writing is not your puppy or boyfriend or married lover. The best thing about your writing, and the only thing you can control, is to change it before it goes out into the world. Be proud of it, but don’t be precious.

The second thing I would say is that for everything that you publish, there will often be at least three times that amount of writing that didn’t make it. It could be manuscripts that you abandoned or stories you couldn’t finish. That is part of the process. Everything is not going to come to completion or have the blessings of the market, or even your own blessings. Abandoned projects are meant to exist, and you shouldn’t feel bad about them.

Finally, work on your writing constantly. You can’t be a writer by speaking about it, or networking, or turning up at festivals. Do the hard work, get the words out. Also, on the subject of writer’s block, what I recommend is working on two or three different projects at the same time. That way, if you get bored or stuck on one project, there’s always something else to do. If writers don’t write, they are very miserable with everybody around them. So, to keep the social peace, occupy yourself.

FB: I’m very intrigued by your experience of documenting the work of the female combatant fighters in the Tamil Eelam. How was that experience, and can you share your thoughts on documenting women’s role in war and society?

MK: I grew up in a certain milieu, you know; Tamil Nadu in the eighties and nineties supported the struggle for Tamil self-determination in Sri Lanka. A lot of radical Tamils looked up to the fighters. I went and met female Tiger combatants who had survived the genocide, but were later brutalized by rape in military camps. After the end of the war, the fighters were trying to escape to Europe, and the fact that they were once at the frontline of the war was a hindrance. What skills did they have?

Now people are talking about Ukraine, and the refugees from there, but Eelam Tamil refugees are still locked up in detention centres in the UK, where they are paid £1 an hour. Their living conditions are miserable, a lot of them have ankle tags. They were something in society’s eyes, and then overnight they were completely mistreated, almost criminalized. It’s heart-breaking.

Also read: Shah Rukh Khan is a great way to get handsome discounts when Indians travel abroad

FB: Does the inevitable burnout from your work as an activist affect your writing?

MK: No, I don’t think it happens at all. I think there’s no perfect writing desk, perfect writing time, whatever. I don’t think that’s how writers function. One of my most powerful pieces, at least in my eyes, was an op-ed that I wrote for The Hindu in 2016, in response to the death by suicide of the Dalit scholar Rohith Vemula. I was taking part in a protest march and at one point I was on stage, and I started writing the op-ed on my phone. I wrote 800–900 words. I was reflecting the anger of millions of people, or at least the anger of those at the protest. I was part of a moment and my op-ed was a collective response. I remember writing to whoever had commissioned it saying, ‘I’m composing this on a phone, but you will get it by tonight’, and by the end of the meeting, I had finished it.

FB: How did you navigate translating the works of women who were poets but also fighters in the resistance, from the language they were writing in, i.e., Tamil, into a language such as English which carries its own legacy of violence and colonialism?

MK: I don’t think of English as a colonial construct, because what does English mean to people from the margins? Well, English people can be pretentious about accents, but you can also be like, ‘Oh, fuck you!’ You can’t do the same thing with Tamil, because you realize the enormity of the system that’s weighing down on you.

Also, even if English is a colonial language, we’ve been speaking it for 300 years. This return to indigeneity project has been appropriated by the RSS and the BJP. I think English actually connects us a lot, because the second or third generation of the diaspora of Eelam Tamils speak English, more than Tamil, and for them this is their history; it doesn’t matter whether they get the history of their people in Tamil or English, they still get their history.

FB: In an interview you talked about how the avant-garde experimental form is more intuitively accessible for DBA [Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi] writers, but that the publishing ecosystem pushes us to follow a template, far more sternly than is allowed to UC [upper caste] authors. How does one reconcile with this?

MK: With experimental work, especially with poetry, you can show that you don’t want to be conventional, you don’t want to be read the way some people may want to read you. You can pose a challenge to the reader, but the question is, would I recommend it? I would be such a hypocrite if I didn’t tell the truth. A very close friend and editor, who has been with me for ten years now, told me, ‘Meena, if we use the word experimental on the cover of your book, people will not buy it. We can say anything else, but we can’t use the word experimental.’

Experimental is a word that keeps away publishers. It’s a fact. It’s not only among Bahujan writers or oppressed writers, there’s a tendency among those who write experimental literature to make it so obscure that it takes away from the content of the story, or begs the question, ‘Why this experiment?’ The other thing I would say is that, write what you have to write, do write the way it comes out and publication can always happen later, or in another form.

This excerpt from ‘How I Write: Writers on Their Craft’, edited by Sonia Faleiro, has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from ‘How I Write: Writers on Their Craft’, edited by Sonia Faleiro, has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

The article ” Your writing isn’t your puppy, boyfriend, or married lover: Meena Kandasamy to Fatima Bhutto ” is very interested. A woman can write many things as matter of emotional but not like a close relative. But one thing is true the differences of language in peace or threaten mode is accepted to literal community . The style of writings always d8fferes according to the situation of the time and incidents.

Two of a kind. Good for nothings, born into royalty and privilege, having a good time. No worthwhile discussion is to be expected from such useless people.

Some people are just plain lucky to be born in certain families. Nepotism rules the world.

Two idiots, both products of nepotism, talking to each other.